Research Article: 2022 Vol: 26 Issue: 3

Policy and Regulatory Initiatives for the Short-Term Rental Sector: A Focus on Airbnb

Emeka Ndaguba, Edith Cowan University

Kerry Brown, Edith Cowan University

Uma Jogulu, Edith Cowan University

Dora Marinova, Curtin University

Citation Information: Ndaguba, E., Brown, K., Jogulu, U., & Marinova, D. (2022). Policy and regulatory initiatives for the shortterm rental sector: a focus on airbnb. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 26(3), 1-12.

Abstract

Policy and administrative inventiveness for regulating business-to-individual relationship is incongruent. Government legislations and local government administrative laws for business-to-individual relationships in the short-term rental arrangement generates two kinds of laws: location-based and density-based, which tend to create confusion and inconvenience for both the owners, investors and guests. This paper assesses the role of administrative personnel of the local government and the regulation initiatives implementable in the governance of the short-term rental sector in Australia. We utilise text, content, and document analysis to gather data to create contexts and produce insights. Our result established a differential in states and local governments laws on short-term rentals in Australia, and these laws may affect the local and international property investors and management firms, and may create a lacuna in local economic development, by reducing guest stay in some local governments, while other may witness deficit in housing investment for short-stay accommodation. We further established that regulatory fluctuation creates misunderstanding for consumer’s booking intention, accommodation platforms, and travel and sales apathy. Also, an inconsistency in administrative law may prevents buyers from comparing housing market indices. Thus, there is a need for smart regulatory framework, which unlocks and stimulates economic regeneration, and build scalable public value and sustainable finance for majority of its users.

Keywords

Airbnb, Policy Alternative, Regulatory Theory, Responsive Regulation, Short-Term Rental Accommodation, Smart Regulation.

Introduction

The study of the concept of regulation and administrative law has generated diverse interests with the advent of disruptive innovation (Brummer, 2015; Cortez, 2014). Scholars and practitioners hold different views on the right manner for regulating disruptive innovation, such as Airbnb (Nieuwland & van Melik, 2018). While most scholars and practitioners are reluctant about the implication of their decision on the (de)growth in the sector (Braithwaite, 2017; Cotterell et al., 2019), regulations appear geopolitical. For instance, local government in the United States of America formulate policies for the Short-Term Rentals (STR) (Guttentag, 2015). In Berlin, the central government provides legislations for the use of Airbnb. However, in Australia, the state has taken the lead in regulating the sector, while the local governments are weighing their course of action. Notably, prioritising innovations that upscales events and act as catalyst for development is key to unlocking the post-pandemic crisis. To set the tone of event, it is important to decipher complex assumptions concerning meaning, mission, and the difficulty in regulating disruptive innovation.

Disruptive innovation is any perceived technological change that results in the destruction (see destructive creative by of an existing big firm by a smaller firm or a group of individuals. A fundamental dilemma in the 21st century is the erratic and challenging effect of technological advancement in the STR sector (Kilkki et al., 2018), and the potential of Airbnb to crowd-out well-managed or successful hotels and other STR providers (Christensen & Raynor, 2013).

Contrarily, O'Ryan in Lindgren (2018) argue that effective integration of forward-thinking, new and existing innovative practices in a hotel can improve its benefits. Implicit in these arguments is that without managerial and futuristic cognitive perceptions of leaders, whether a firm adopt, ignore, or adapt technological change, the complex nature in a business environment will remain.

The business environment for STR remains hostile due to deficient local government laws or framework for governing the sector. Globally there are two main regulatory initiatives for STRs, namely, prohibition and limitation. However, in Australia, the laissez-faires approach appears to be more appealing. The strategy for regulating STRs arrangements in Australia is limited two provocative outcomes, limitation and prohibition approach, which may be considered as sanctions than laws.

While the prohibition clause creates economic deficits to firms, hosts, management firms and communities. The full potential of Airbnb and other member of the digital STRs may never be realised. However, where the laissez-faires approach is prevalent in Australia, the communities are seeking for some sort of regulation (Parliament of Victoria, 2017).

The uniqueness of Airbnb and others is that it is host driven and people centred. Thus, the administrative laws governing Airbnb and other platform accommodation must not be restricted to limitation or prohibition. in essence, cognisance must be given to the stakeholders in this market, which are not limited to the community, the host and government officials in the local communities.

Moreover, issues of how to regulate STRs are multifaceted, especially when regulation in some part of the globe, such as San Francisco, New York City, Berlin amongst others demonstrate a degrowth in the economic vivacity of the tourist destination. The STR sector has proven to incentivise hosts by providing both economic and psychological opportunities. Furthermore STRs contributes to the experience economy, travel and hospitality and tourism economy, sharing economy, collaborative consumption and the public finance of local government and to some extent stimulate sustainability. Whether a relationship exists between regulating STR and degrowth in the industry in Australia is not empirically tested, however, when strict laws were implemented in San Francisco and New York City, the number of hosts plummeted by half. Also, in Victoria, where the prohibition clause is applied due to strata corporation guidelines, it has resulted in wastage in public finance through litigations (see the case between Swan v Uecker, Dobrohotoff v Bennic, Genco v Salter, and Owners Corporation PS 501391P v Balcombe) (Ritchie & Grigg, 2019).

In this paper, we look at various regulatory regimes such as responsive regulation and how they assist in policy and administrative reforms for STR in Australia. For convenience, the paper is divided into different sections: the literature review section, houses the foundation of regulatory prowess based on the regulatory theory of Braithwaite and the place of responsive regulatory in the digital space, before creating a conceptual grasp of the short-term rental. The methodological section exhibits the nature of data coding and sourcing. The discussion section speaks to the complexity of regulating digital platform and the place of local government personnel in law enforcement in the STR sector. This ushers in our proposition of the Community of Host. Where we argue that the Community of Host is a bridge between the prohibition and limitation clauses for local governments seeking policy and administrative alternatives for regulating the digital platform industry, thereafter a conclusion. However, before all of these sections unfold, the regulatory theory as part of the literature review set the scene.

Literature Review

In this paper, we utilise the regulatory theory and responsive regulation advanced by Braithwaite (1985;2006); Braithwaite (2017) respectively, as the foundation for which we assess the policy and administrative alternatives for STRs in Australia. While the regulatory theory assists in developing a perspective on the complexity of regulation in STR, and the use of powerplay, persuasion and sanctions in instilling compliance, the responsive regulatory perception tends to empower stakeholders through deliberations.

Regulation and Regulatory theory

Public policy and administrative law are complex mixture of ideas with multiple layers. For instance, a law on STR, inadvertently stipulate guidelines for guests, neighbourhoods and hosts behaviour. More profound in literature is that it deals with the number of stays, and sometimes, dictates the amount charged per apartment per night. The effect of limiting the number of stays has an implication for sustainable finance of the host/ owner, reaching the superhost status, overall rating, cancellation policy, and listing types amongst others.

Beer (2014) argues that regulatory theory deals with a mixture of persuasion and sanction (stick and carrot). The actions of government agencies in persuading or sanctioning STR providers has a multiplier effect on the rules made, the nature of the adjudication of the law and the enforcement mechanisms, constitute the tripartite alliance required for creating a level playing field in the sector.

It has been recounted that STR in San Francisco and New York City in the United States leans towards sanctions. NSW, Queensland and Tasmania provide a unique win-win approach for the sector (Tasmanian Government, 2020). Due to the perception of the sector on the local economy. Particularly, the laws in Queensland freely allow the STR to operate without limitation, however, the party-houses needs approval.

Legislation or administrative providing guidance for the STR sector, there are several factors local government must consider: the environment, the community, the social and economic benefit to the local area, the sustainability threats and stakeholder stance. However, in this paper, we would concentrate on two of these factors, the economy, and the law. Several research papers on economics and regulations (Braithwaite & Drahos, 2000) account for this relationship. From topics ranging from Coase theorem by Ronald Harry Coase to external cost versus external benefit. Blockchain and artificial intelligence, among others such as market failures and government finance, alternative modalities for trade permit and command control.

Literature on STR demonstrates three regulatory stance-full prohibition, the laissez-faire, and the limitation approach (Guttentag, 2015; Jefferson-Jones, 2014; Nieuwland & Van Melik, 2020). Full prohibition is the outright sanction of STR from the tourist accommodation market (Jefferson-Jones, 2014), as depicted in Berlin and Santa Monica. According to Lines (2015), the laissez-faire approach cannot be considered a regulatory framework since it failed to provide a guideline for operability. The limitation approach provides procedures for limiting the usage of an apartment, which may include limiting the number of stays, the number of guest per night, and the number of times an apartment can be Listed per year (Gottlieb, 2013; Guttentag, 2015). Within the limitation framework for STR, restrictions can be location-based or density-based. When it is location-based, the regulation is confined to a given geographical area as witnessed in NSW (Gurran & Phibbs, 2017; Nieuwland & van Melik, 2018). When it is density-based, however, it provides guidelines for the limitation of STR within a neighbourhood or community (Jefferson-Jones, 2014) resulting in several complexities that have resulted in litigations, as depicted in Victoria.

One of the reasons for the complexity in regulation is because the philosophy of regulation is vague, unlike tort theory, property theory, contract theory or criminal law. The seminal book of Stephen Breyer on "Regulation and Its Reform" published in 1982, which acted as the bible of law stipulate as part of its opening pages that no serious effort is made to define 'regulation'. This statement by a book considered as the bible of regulation exhibit the complexity associated with providing clarity on the subject matter. Thus, avenues through which the STR complexities are reduced, and the governance of the sector more adaptive towards supporting personnel of the local government who monitor the STRs and ensure both compliance and enforcement is long overdue.

Methodology and Results

This paper adopts the qualitative architecture for data collection and analysis. It combines the Traditional Text Analysis (TTA), document and content analysis supported with empirical data from MadeComfy to frame a perspective on policy initiative for regulation short-term rental arrangement in Australia. While the TTA and content analysis were utilised as a survey method that assists in producing insightful discourse within a specific perspective (Cheng & Edwards, 2019), document analysis was used to gather laws, legal cases, and Acts for regulating STRs in Australia. TTA helps in creating a context for research, while data provided macroeconomic data on short-term rental in Australia.

Document analysis, on the other hand, is also qualitative research which uses brochure or documents to give a pathway around a subject matter (Bowen, 2009). Interpreting documents involves the coding of content into themes; however, there are three types of document analysis: public records, personal document and physical document. In this paper, the public records techniques were used to gather data from annual reports, gazette, policy manuals, and planning and strategic document of states and local governments in Australia.

The technique for gathering data under text and content analysis involves manually surveying data from different secondary sources from academic journals, (academic) textbooks, newsfeeds, blogs, and newspaper articles, among others. While document analysis enabled the study to generate and triangulate information regarding the NSW Option Paper, the Victorian Civil & Administrative Tribunal and the Strata Corporation Owners in Victoria, Section 276(2) of the Planning Act, 2016 in Queensland, the Short-Stay Accommodation Act, 2019 in Tasmania, and the recommendations in Western Australia (NSW, 2017; Parliament of Victoria, 2017; Tasmanian Government, 2020) to generate Table 1.

| Table 1 Regulation Governing Str In Australia |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Policy framework | Restriction of SSA | Sanctions | Building requirements | Tax | Regulatory outlook |

| New South Wales | The policy document balances the economic value vs the impact on the community.

With a combination of three measures:

Land-use planning law mechanism. Consumer protection law and the Code of Conduct for short-term accommodation; and Strata corporations to make bylaws. |

SSA is restricted to the residence of the host for 365 days a year if the host resides there. Where the host is absent from the property, the host is permitted to rent for a total of 180 days in a year, including holidays and weekends Outside Greater Sydney, a host could rent for a total of 365 days. Outside GS, councils within regions are permitted to regulated, not decreasing below the 180 days per year stipulation. Sub-letting without permission is not permitted for STR. | A breach of two strikes within 24 months will result in a penalty of a five-year ban.

Section 258 of the Strata Schemes Management Act, 2015 stipulates that owners who do not register 'stayers' (by providing names and address) within fourteen days be fined a maximum of AU550. |

No legislation on building requirement | The NSW Option Paper is silent on tax issues. | State regulation but regions outside Greater Sydney may provide further regulation. |

| Victoria | The policy document attempt to balance SSA by increasing the powers accorded to Strata Corporation Owners. Ideals of self-regulation and citizen enforcement/ policing are optimised, owners are bound to balance any adverse impact of SSA. It implemented the Owners Corporations Amendment Act 2018 on February 1 2019 | There is no limitation to the number of 'stays' in short-stay accommodation in Victoria. | The Victorian Civil & Administrative Tribunal has the powers to prohibit occupant of short-stay accommodation, where there have been three complaints of the occupant within 24 months. Award compensation is capped at AU2,000 for each affect occupier. Award of a civil penalty against a short-term occupant is capped at AU1,100. | The focus is on the impact of safety and health of those in the building. | The Strata Corporation Owners, Victorian Civil & Administrative Tribunal and Owners Corporations Amendment Act of 2018 was silent on tax issues. | A state-wide regulation is implemented. |

| Queensland | The approach by the Queensland government for SSA arrangement adopted the land-use planning law and policy framework for regulating the impact of the use of SSA for commercial purposes on the neighbours and the amenity in a community. Hosts require planning approval. | Section 276(2) of the Planning Act, 2016 restricts party houses, not necessarily limiting the use of STR. Party-houses are limited to less than ten days per approval, where the owner of the premises does not dwell in the apartment. Noosa Shire Council declares that there shall be no food preparation equipment or facility in SSA apartments. Sub-letting is not permitted for STR. |

A penalty of AU180 is attached as a penalty for non-compliance of tax rules. | There exist no nothing in the private class for Queensland which excludes SSA use of the lot. | Monies earned by renting an apartment on SSA must be declared to the tax office. | While the Queensland government has its regulation governing SSA in the state, local councils also provide further ordinance to regulate disruptive behaviour of the guest and the host. |

| Tasmania | The policy document of the Short-Stay Accommodation Act, 2019 will take effect from June 4, 2019.

Tasmania SSA Act requires SSA host to provide information relating to the booking platform provider (examples of booking platforms providers are HomeAway, Airbnb, and Booking.com). Before entering into any formal agreement with the booking platform provider. Permits are required for hosting in Tasmania. |

Restrictions follow the planning scheme zones. The SSA Act identified four zones - General Residential Zone, Inner Residential Zone, Low-Density Residential Zone, Activity Area 1.0 Inner City Residential (Wapping), Rural Living Zone, Environmental Living Zone, and the Village Zone. | Non-compliance to the booking platform provider law may result in 16,300 for 100 penalty units per premises and 1,630 for ten penalty units per day. The same penalty in fees exists for a host who does not display the required information on the booking platform. The same penalty in fees applies, where the host did not provide the requisite information to the Director of Building Control within 30 days on each premise at the end of the fiscal quarter. | Clause 4.0.2 of the State Planning Provisions and Clause 5.0.2 of all Interim Planning Schemes stipulates that a planning permit is not required, as existing use rights of a building applies for SSA apartment in Tasmania. However, approval is required from the Director of Building Control based on Section 20(1)(e) of the Building Act 2016, effective July 1, 2018 | The SSA Act is silent on tax | A state-wide regulation is adopted. |

For Western Australia, Northern Territory, South Australia, and Australian Capital Territory policies for STR seem blurry. For instance, in the Northern Territory, South Australia, and Australian Capital Territory, concerns for policy streams in regulating the STR sector are heightened by the formal tourism accommodation sector and the partying behaviour of guest (Parliament of Victoria, 2017). In Western Australia, about 45 findings were presented. However, the Government of Western Australia seems to pitch Airbnb side by side with hotels. Thereby feeding into the rivalry orchestrated by hotel providers, rather than perceive Airbnb as alternative tourist accommodation based on tourist preference. More so, where Airbnb was ban entirely in Berlin, Germany, Homestay, a local STR emerged; hence, business opportunities do not survive in a vacuum. The choice of limiting individuals' prowess and anti-competitive spirit is the bane of entrepreneurship and the downside to agile development in the tourist accommodation sector (Fels, 2004).

Discussion

Policies are a complex mixture of ideas with far-reaching consequences. Such as, a law on STR will inadvertently stipulate guidelines for tourist and host behaviour or conduct. Regulate the number of stays (under limitation clause) and ban the use of Airbnb (under prohibition clause) (Parliament of Victoria, 2017). In some cases, it will provide stakeholders with a fee structure for an apartment (like in Germany) (Lladós-Masllorens & Meseguer-Artola, 2020). Other policy stipulations, sanction users for non-compliance, on the other hand, some put the burden on the host (see Victoria laws on STR) (Parliament of Victoria, 2017) because Airbnb always recused itself from culpability as a platform provider, not a content provider (Lawson et al., 2016). However, while NSW created a Coded of Conduct Bureau for monitoring and enforcement several do not (Parliament of Victoria, 2017; Tasmanian Government, 2020). Thus, in this sense, regulation may involve a composite web relationship, which in most cases are bidirectional, composed of several components or set of rules that bind (in our case) host, guest, community, and the local government.

Moreover, in several ramifications, state and local governments differ in the way they regulate and maintain the STR register (see NSW), while some do not require a booking entry (see South Australia). Although, there are requirements for operating STR, which may include that host is required to maintain the national tax obligation, support local regulation in the locality (in some areas) and seek permission. Nevertheless, these requirements and legislations differ from one local government to the next, making it difficult for the guest to comply with the level of regulatory flexibility and for investors to reinvest in the local economy.

A novel focus on regulation studies is the awareness of policymakers in leading the future of the digital market through legislations. Thus, providing quality regulation for effective governance of the digital economy and disruptive innovation is vital. At the centreof quality regulations for the digital future is dependent on 'tech-savvy policymakers and leaders.' In recent times, the disruption of existing business models and the difficulty in local government bylaws to catch-up have proven much complicated. One of the many reasons for this complexity is that business regulation has been on business organisations (Espinosa, 2016), not business-individual/s such as entrepreneurs and sole proprietors. This missed opportunity, lag or failure on the part of policymakers have created a spill-over effect that has made the digital platforms for tourism accommodation complex to regulate.

In modern tourism accommodation philosophy, a host is perceived as a micro-entrepreneur (Lutz & Newlands, 2018). A host is a person or group of persons who offers to share their home, castle or apartment to generate income via a platform called Airbnb (Belk, 2007). By extension, entrepreneurs are individuals who convert opportunities into marketable and workable concepts by applying their money, effort and time to get their project, merchandise or service into the marketplace (Bahena-Álvarez et al., 2019). This is typical of an ideal host on Airbnb. An ideal host strives to market their property to attract more bookings by adapting certain features of Airbnb such as Airbnb Plus, Airbnb Experience and the Instant Book feature to accelerate guest book experience. To achieve this height on the platform, time expended in acquiring knowledge about tourist area, soft and interpersonal skill, investment, and the flexibility of the host is essential.

Regulation in a dynamic era requires active deliberation, which is the basis for deliberative democracy in decision-making (Gutmann & Thompson, 2009). The study argues that for legislations on the STR to be cordial, reflective, and all-encompassing, it must provide an avenue where all stakeholders will partake in the policy circle. The hierarchical and top-down decision models adopted for centuries have become moribund, due to digital connectivity and the introduction of the New Economy - platform economy, collaborative economy, the experience economy, and digital economy. Thus, there is a need to shift legislation where governance appears to be nodal, agile, and networked. For instance, the success stories of the private-public partnership provide the needed motivation for a policy alternative. These success stories in several developing countries such as South Africa, Brasil, India, and Nigeria, among others, demonstrates the need for the replication of such initiative in the regulation of disruptive services.

Moreover, issues concerning the monitoring of digital platforms are both time-consuming and very expensive for the local government. At a time, when COVID-19 has stretched sparse government resources, and government debt profile has risen tremendously. Unemployment rising with a recession in view, and errant behaviour of tourist and host cannot be micro-managed by the local council (Baldwin & Black, 2008). A new regulatory perspective may assist in reducing the burden on the government in the STR sector. Hence, we introduce what we call the Community of Host to bridge the laws governing the STR sector in Australia.

In sum, policy decision-making traditionally is based on power relation, coercion, persuasion and sanctions (Braithwaite & Drahos, 2000). Nevertheless, the digital economy and the disruptive innovation service provide a flexible approach for exchange. Thus, the policy circle governing the sector can no longer be restricted to limitation and prohibition clauses.

The Community of Host Approach

Albert Einstein once said, "once you stop learning, you start dying." Perhaps this may also translate as 'once you stop reinventing yourself, you start dying.' The perception of Einstein and our example is what developed into what he called sustaining innovation. Sustaining innovation leans towards the reinforcement or the rebranding of existing business models, routines and technologies for improved performance of a firm (Christensen & Raynor, 2013). Though it may not lead to the creation of a new product or market, it leans towards rebranding its features and adding more attributes to an existing product or service to either boast its outlook or make more market-oriented (Feder, 2018).

Airbnb has been evolving from adopting new titles in China to supporting host with palliatives during coronavirus disease pandemic, and the introduction of the Instant Book feature, Airbnb Plus and Airbnb Experience to optimise its performance (Ramaswamy & Ozcan, 2018). Furthermore, it appears the factors of production are fast challenged from land, labour, capital and enterprise to much complex production techniques dealing with artificial intelligence, social innovation, 5G, digital communication and infrastructure. Also, sustainable digital transformation, access and adoption, robotics, cybersecurity, data management, digital identity and the Internet of Things. Times have changed, and the modus operandi of regulation yet remains the same. Thus, attempting to utilise the instrumentalities for regulating the old economic system on the agile digital system may not only create conflict but constitute severe scholarly transgression. We contend that the modalities for regulation based on prohibition, limitation and laissez-faire are archaic and not suitable for the digital economy.

The preceding analysis does not dismiss in its entirety, the proposition of Guttentag (2015); Jefferson-Jones (2014); Nieuwland & Van Melik (2020) among others, on full prohibition, the laissez-faire and the limitation approach. However, it demonstrates that old regulatory philosophy may be antithetical to the growth and development of digital platforms such as Airbnb.

The notion that policymakers have failed over the years to regulate similar sectors such as Email services, online stores (like Alibaba), WhatsApp among several disruptive initiatives and firms shows that it does not have the capability and capacity to do so. Thus, the non-regulations of the earlier digital platforms have created a gap in the regulatory regime for local government.

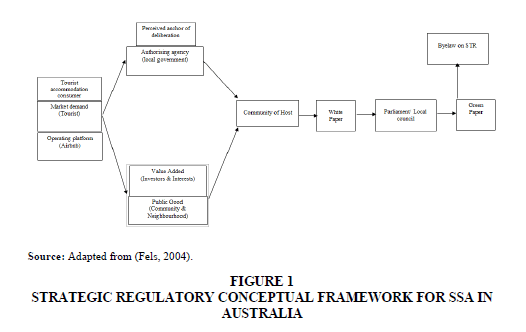

Thus, the need for policies in the digital atmosphere to be responsive and flexible is unequivocal. To this end, we propose a regulatory conceptual framework, with the Community of Host at the centre of regulation. We believe that the Community of Host may change the perception of regulation for the STR sector, and how monitoring and compliance may not be out of the pocket of local governments. This policy alternative is particularly needful at a time when the COVID-19 have depleted the reserve of most local government and created a huge debt burden on others. Avenues through which government can earn income without expenditure is essential. Hence, our preposition of strategic policy conceptual framework for STR in Australia, also known as the Community of Hosts (Figure 1).

The essence of every smart and responsible regulation is to improve what it perceives to be a public good. In that, the improvement in the welfare and wellbeing of the people is the Achille hills of legislation. The strategic regulatory framework for STR in Australia situates the harbinger of regulation within the bounds of the Community of Host. We believe that the Community of Host is the only variable that requires elucidation. In that, the relationship between demand and value-added is established, and Airbnb Listings and value is also considerably discussed elsewhere. However, whether value-added may lead to public good may be contextual. However, when we consider, the employment opportunities afforded and the indirect contribution of the guest in the local economy. We believe that for neighbourhoods and communities not to lose the economic and psychological benefits, the Community of Host should be adequately constituted.

Composition of the Community of Host

The composition of the Community of Host should be neighbourhoods and residents. The configuration of this Community must include, among others:

1. Legal luminaries in the area,

2. Representatives from the local government,

3. Hosts on different platforms,

4. Residents,

5. Stakeholders, investors and hoteliers, and

6. Tourist

The composition and deliberation therein should evolve into a White Paper presented to the local council for deliberation and accent. This is what Braithwaite (2006) expected would resolve into what they perceive as responsible legislation, and what Gutmann and Thompson (2009); Nabatchi (2010) believes to constitute tenets of deliberative democracy.

The need for the Community of Host cannot be overemphasised. The poorly equipped system in New York and some parts of Europe such as London have led to the rise of illegal apartment rentals on STR. This failure in other parts of Europe like Barcelona and Venice has led to the rise in the cost of longer-stay accommodation or real estate with the Community of Host located within neighbourhoods, it will be easier to track illegal listing and report infringement much easier than a local government-led enforcement agency. Particularly, considering that the members of the Community of Host reside in the community where they chair.

Lastly, the COVID-19 era is demonstrating that everything will never be the same. Therefore, so long as there are market new entrants will emerge, and competitors and rivalry will persist. The challenge going forward is where there are no challengers or competitors due to prohibition laws or a regulation that tames the individuals' (hosts) prowess in communities.

Findings

Analysis in this paper demonstrates a unique challenge in regulating disruptive innovative platforms such as Airbnb, which establishes that there is no universally accepted framework for regulating the business-to-customer-society relationship. Despite years of legislation for business-to-business relationship (Espinosa, 2016). The study shows that various states in Australia such as New South Wales, Tasmania, Victoria, Canberra, Queensland, and South and Western Australia have adopted their regulatory regimes based on three global approaches: prohibition, limitation and laissez-faire approach (Guttentag, 2015; Jefferson-Jones, 2014). While, Tasmania, New South Wales and Victoria to some extent adopt the limitation approach. Canberra, Queensland, and South and Western Australia appear to apply the liberal approach of laissez-faire. Although the NSW Option Paper adopted limitation in Greater Sydney, it offered the laissez-faire clause for regions and local governments outside the Greater Sydney. The Strata Corporation Owners, Victorian Civil & Administrative Tribunal and Owners Corporations Amendment Act, 2018 and the Tasmania Short-Stay Accommodation Act, 2019 also adopted the limitation approach. However, the Strata Corporation Owners limitation is based on location-based (Parliament of Victoria, 2017), while the Tasmania SSA Act is based on zones (Table 1) (Tasmanian Government, 2020). Nonetheless, for Queensland and other states, permission needs to be sorted for a house party, not for digital rental services.

Conclusion

In conclusion, what is of concern here is that there are two approaches adopted in Australia - prohibition and limitation approach, but we still have an alternative. The essence of policy alternative is in tandem with success stories of private-public partnership globally, the ideals of self-regulations demonstrated by the Victorian Civil & Administrative Tribunal Act and the temerity of such a partnership and self-regulatory framework to accelerate the economic, psychological, social and cultural potential of the STR sector. Additionally, with the increasing loss of jobs during COVID-19 and the height of uncertainty after that, an approach that is ethical, responsive and smart is needful to pull the Australian economy from the recession. Taking into cognisance that most banks within Australia have suspended their mortgage payment for six months, after the COVID-19 era, the mortgage stress is expected to heighten, especially where mortgage stress and home indebtedness are at an all-time high before COVID-1. None of these policies (prohibition, laissez-faire, or limitation approach) offers hosts and investors' confidence in looking into the future.

References

Bahena-Álvarez, I.L., Cordón-Pozo, E., & Delgado-Cruz, A. (2019). Social entrepreneurship in the conduct of responsible innovation: Analysis cluster in Mexican SMEs. Sustainability, 11(13), 3714.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Baldwin, R., & Black, J. (2008). Really responsive regulation. The Modern Law Review, 71(1), 59-94.

Indexed at, Google Schoalr, Cross Ref

Belk, R. (2007). Why not share rather than own. The Annals of the American Academy of Political Social Science, 611(1), 126-140.

Indexed at, Google Schoalr, Cross Ref

Bowen, G.A. (2009). Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9(2), 27.

Indexed at, Google Schoalr, Cross Ref

Braithwaite, J. (1985). To punish or persuade: Enforcement of coal mine safety. NY; New York: SUNY Press.

Braithwaite, J. (2006). Responsive regulation and developing economies. World Development, 34(5), 884-898.

Indexed at, Google Schoalr, Cross Ref

Braithwaite, J., & Drahos, P. (2000). Global business regulation. Cambridge university press.

Braithwaite, V. (2017). Closing the gap between regulation and the community. Regulatory theory: Foundations and applications, 25-42.

Brummer, C. (2015). Disruptive technology and securities regulation. Fordham Law Review., 84, 977.

Cheng, M., & Edwards, D. (2019). A comparative automated content analysis approach on the review of the sharing economy discourse in tourism and hospitality. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(1), 35-49.

Indexed at, Google Schoalr, Cross Ref

Christensen, C., & Raynor, M. (2013). The innovator's solution: Creating and sustaining successful growth. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press.

Cortez, N. (2014). Regulating disruptive innovation. Berkeley Technology. LJ, 29, 175.

Indexed at, Google Schoalr, Cross Ref

Cotterell, D., Hales, R., Arcodia, C., & Ferreira, J.A. (2019). Overcommitted to tourism and under committed to sustainability: The urgency of teaching strong sustainability in tourism courses. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1-21.

Indexed at, Google Schoalr, Cross Ref

Espinosa, T.P. (2016). The cost of sharing and the common law: How to address the negative externalities of home-sharing, 19, 597.

Feder, C. (2018). The effects of disruptive innovations on productivity. Technological Forecasting Social Change, 126(C), 186-193.

Indexed at, Google Schoalr, Cross Ref

Fels, A. (2004). Regulating markets: Marketing regulation. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 63(4), 29-36.

Gottlieb, C. (2013). Residential short-term rentals: should local governments regulate the'industry'. Planning & Environmental Law, 65(2), 4-9.

Gurran, N., & Phibbs, P. (2017). When tourists move in: how should urban planners respond to Airbnb. Journal of the American Planning Association, 83(1), 80-92.

Gutmann, A., & Thompson, D.F. (2009). Why deliberative democracy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Indexed at, Google Schoalr, Cross Ref

Guttentag, D. (2015). Airbnb: disruptive innovation and the rise of an informal tourism accommodation sector. Current Issues in Tourism, 18(12), 1192-1217.

Indexed at, Google Schoalr, Cross Ref

Jefferson-Jones, J. (2014). Airbnb and the housing segment of the modern sharing economy: Are short-term rental restrictions an unconstitutional taking. Hastings Construction. LQ, 42, 557.

Kilkki, K., Mäntylä, M., Karhu, K., Hämmäinen, H., & Ailisto, H. (2018). A disruption framework. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 129, 275-284.

Indexed at, Google Schoalr, Cross Ref

Lawson, S.J., Gleim, M.R., Perren, R., & Hwang, J. (2016). Freedom from ownership: An exploration of access-based consumption. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 2615-2623.

Indexed at, Google Schoalr, Cross Ref

Lindgren, P. (2018). Disruptive, radical and incremental multi business model innovation. Paper presented at the 2018 Global Wireless Summit (GWS).

Lines, G.E. (2015). Hej, not hej da: regulating airbnb in the new age of arizona vacation rentals. Arizona Law Review., 57, 1163.

Lladós-Masllorens, J., & Meseguer-Artola, A. (2020). Pricing Rental Tourist Accommodation: Airbnb in Barcelona. In J. Lladós-Masllorens & A. Meseguer-Artola (Eds.), Sharing Economy and the Impact of Collaborative Consumption, 51-68. Germany: IGI Global.

Indexed at, Google Schoalr, Cross Ref

Lutz, C., & Newlands, G. (2018). Consumer segmentation within the sharing economy: The case of Airbnb. Journal of Business Research, 88, 187-196.

Indexed at, Google Schoalr, Cross Ref

Nabatchi, T. (2010). Deliberative democracy: The effects of participation on political efficacy. (Doctoral), Indiana University Indiana.

Nieuwland, S., & van Melik, R. (2018). Regulating Airbnb: how cities deal with perceived negative externalities of short-term rentals. Current Issues in Tourism, 1-15.

Indexed at, Google Schoalr, Cross Ref

Parliament of Victoria. (2017). Victorian Government response to the Environment and Planning Committee’s Inquiry into the Owners Corporations Amendment (Shortstay Accommodation) Bill 2016.

Ramaswamy, V., & Ozcan, K. (2018). What is co-creation? An interactional creation framework and its implications for value creation. Journal of Business Research, 84, 196-205.

Indexed at, Google Schoalr, Cross Ref

Ritchie, C., & Grigg, B. (2019). No Longer unregulated, but still controversial: Home sharing and the sharing econcomy. UNSWLJ, 42, 981-1017.

Tasmanian Government. (2020). Short Stay Accommodation Act 2019: Overview. Retrieved from State of Tasmania

Received: 05-Mar-2022, Manuscript No. AMSJ-22-11480; Editor assigned: 07-Mar-2022, PreQC No. AMSJ-22-11480(PQ); Reviewed: 21-Mar-2022, QC No. AMSJ-22-11480; Revised: 23-Mar-2022, Manuscript No. AMSJ-22-11480(R); Published: 28-Mar-2022.