Research Article: 2023 Vol: 27 Issue: 2

Practical Assessment of Good Practices in Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) Analysis: A Study on Consumer Socialization

Eric Bindah, University of Mauritius

Citation Information: Bindah, E. (2023). Practical Assessment of Good Practices in Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) Analysis: A Study on Consumer Socialization. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 27(2), 1-16.

Abstract

This study uncovers how various socialization factors (namely family and peer communication environment and television viewing) in the society could impact on young adult consumers’ orientation towards materialism. Materialism is a value that impact on consumers’ decision making and consumption patterns. This study provides an insight into how specific type of the family communication patterns at home, peer communication and television viewing influence the orientation of materialism among young adult consumers. Structural equation modeling (SEM) technique was adopted in this study. In particular, the researcher first developed the hypothetical general consumer socialization model for young adult consumers through relevant literature review. For the purpose of conducting the literature review, primary data were consistently assessed and relevant literature was organized chronologically in the field of consumer socialization and materialism which determine consumers’ consumption patterns. This step was very important since the method used to analyse the data was based on SEM technique approach, the research framework together with the hypotheses development needed a solid theoretical foundation. This research focuses on discussing the process of SEM analysis. The author briefly covers the procedures adopted for constructing the hypothetical model, testing the model, comparing the models with alternative models, and finalizing the model. Challenges of finalizing the measurements in confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and modifying the consumer socialization model for young adult consumers are discussed. The interrelationships between different dimensions of family and peer communication and materialism are analysed using SEM. This study reviews the basic concepts, terminology and the applications of SEM.

Keywords

Consumer Socialization, Confirmatory Factor Analysis, Structural Equation Modeling (SEM).

Introduction

Materialism among today’s youth has received strong interest among educators, parents, consumer activist and government regulators as young adults are getting more materialistic. Although materialism has long been of interest to consumer researchers, surprisingly research into this area has received little attention from academic researchers. Previous research suggested that, as socializing agents, family communication environment, and peer communication are important agents in influencing the development of materialistic values (Vega et al., 2011; Shrum et al., 2011; Moschis et al., 2011; Shu-Chuan et al., 2012; Adib & El-Bassiouny, 2012; Moschis et al., 2013; DeMotta et al., 2013; Shi & Xie, 2013; Churchill & Moschis, 1979).

Despite the interest in understanding more about materialism, a significant gap in research remains that would be useful in understanding the relationship between social-cognitive development and consumption values such as materialism (John, 1999). At the time where the researcher was conducting this study, most prior studies have investigated how materialism developed among children and adolescents. However, very few studies had focused their research on young adult consumers (Moschis et al., 2009; Moschis et al., 2011; Kau et al., 2000). Hence, this study attempted to fill this research gap.

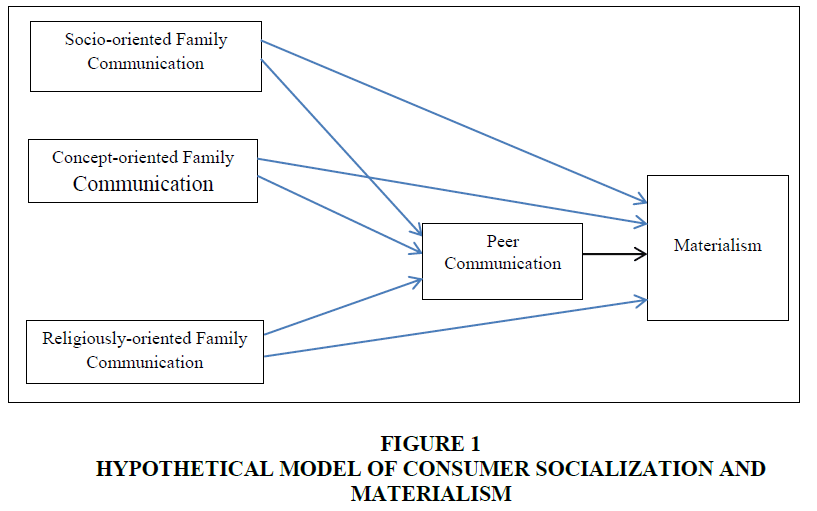

Furthermore, based on prior literature review, it was not clear whether specific socialization agents in general, and communication environment in particular, instilled materialism among people. Based on established theories of consumer socialization, this study attempted to determine if young adult person’s exposure to a socio-oriented, concept-oriented, religiously-oriented family communication structures at home, and peer communication during adolescent years would have an effect on their orientation towards materialism in adulthood. It further attempted to determine if young adult person’s exposure to a socio-oriented, concept-oriented and religiously-oriented family communication structures at home during adolescent years would have any effect on peer communication, and whether peer communication during adolescent years would influence their orientation towards materialism in adulthood. This study predicted that peer communication would mediate the relationship between young adults exposure to a socio-oriented, concept-oriented and religiously-oriented family communication structures at home during adolescent years and their orientation towards materialism in their adulthood. The author further fulfilled a theoretical research gap by examining and exploring the dimension of religiously-oriented family communication structures at home.

The research questions developed for the study led to the investigation of the how various socialization factors could interplay to influence young adults’ orientation towards materialism. The author investigated the extent to which family communication, and peer communication interplayed to affect young adult’s orientation towards materialism.

Theoretical Framework and Foundation

As this study emphasized on the role of family and peer communication and television viewing and how they interplays to affect young adults orientation towards materialism, a conceptual model is needed. The theoretical model of this study is primarily derived from established theories of consumer socialization research.

Based on the literature review, the model of this study posits that young adults who were exposed to a socio-oriented family communication structure at home during adolescent years would tend to be oriented towards materialism in their adulthood as opposed to those who were exposed to a concept-oriented and religiously-oriented family communication structure at home during adolescent years. The relationships between family communication environment were found to be both positive and negative and are supported by relevant literature on consumer socialization and materialism research (Moschis & Moore, 1979a; Carlson et al., 1994; Flouri, 1999; Bristol & Mangelburg, 2005; Moschis et al., 2011; Vega et al., 2011; Moschis et al., 2013; Potvin & Sloane, 1985; Hunsberger, 1985; Benson et al., 1986; Bao et al., 1999; Myers, 1996; Wilson & Sherkat, 1994; Kau et al., 2000; Burroughs & Rindfleisch, 2002).

The model also explains that during young adults’ adolescent years, regardless of the type of family communication structure which existed at home, individuals would interact and communicate with their peers too. This is mainly due to the fact that although the family is considered as the primary force of influence in childhood, but as an individual transit into adolescence, peer influence continuously exerts its influence on the individual as compared to the family (Ward et al., 1977; Churchill & Moschis, 1979; Moschis & Churchill, 1978; Moschis & Moore, 1979a; Moschis & Mitchell, 1986). Furthermore, due to young adults’ interaction and communication with their peers about consumption matters during adolescent years, this may lead to their orientation towards materialism in adulthood (Rindfleisch et al., 1997; John, 1999; Moschis et al.,2009; Moschis & Churchill, 1978; Moore & Moschis, 1981; La Ferle & Chan, 2008; Chaplin & John, 2010; Benmoyal-Bouzaglo & Moschis, 2010; Santos & Fernandes, 2011; Moschis et al., 2013).

The inclusion of peer communication as a mediating variable indicates that peer communication could be a powerful agent of socialization which significantly affects the findings of studies as it may exert more influence and play a greater role in influencing an individual orientation towards materialism (Moschis & Moore, 1982; Moschis et al., 2009; Chia, 2010; Benmoyal-Bouzaglo & Moschis, 2010). Moschis et al. (2013) supported the importance of the possible mediating role of peer communication and it did provide supporting evidence on the important implications of peer communication as a mediating variable, although however, the mediation effect of peer communication was not supported, as the effect of disruptive family events on materialism was not significant. Figure 1 illustrates the hypothetical model of consumer socialization and materialism.

Research Design

This study utilized secondary data for data analysis. The data were collected through a survey among college students in Malaysia, and consisted of 956 complete responses from a diverse urban community college located in Klan Valley region of Malaysia.

Sampling Technique

This study has employed non-probability sampling technique, as it allowed for good estimates of the population characteristics. The method of non-probability sampling technique chosen for the study was based on convenience sampling method. The survey was targeted at college students enrolled in varied courses at both undergraduate and postgraduate programmes. Student samples has widely used in the social and behavioural science as well as marketing and advertising research (Rotfeld, 2003).

Survey Instrument

The survey conducted among young adult consumers was meant to test the hypotheses developed for this study. The scale employed for measuring socio-oriented family communication was adopted and modified from the study of Moschis & Moore (1979b). Socio-oriented communication was measured with seven items. To measure concept-oriented family communication, this study has adopted 5 items from the original study of Moschis et al. (1984) and one item from Moschis & Moore (1979b) study to form the measurement instrument. Religiously-oriented family communication was measured with six items adopted from Rindfleisch et al. (2006) study. The scales were modified to reflect what parents sometimes say or do in their family conversations while their children were growing up. The scales were treated as an interval level of measurement. In terms of psychometric properties, all family communication measures reported good reliabilities across cultures. Peer communication was measured with three items adopted from Benmoyal-Bouzaglo & Moschis (2010). The key construct, materialism, was assessed using previously published, multi-item measures using a five-point Likert format adopted from Wong et al. (2003) study and consisted of 15 items. The scale was treated as an interval level of measurement. In terms of psychometric properties, prior studies reported strong reliabilities for peer communication and materialism measures.

Data Analysis Plan

The data were collected through self-administered questionnaire. The researcher drafted a list of institutions of higher learning and personally collected the data. Out of the 1,200 questionnaires, 956 completed questionnaires were usable for the data analyses. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) 18 version and AMOS 16.0 version were used for statistical analyses. Data were coded for 956 usable questionnaires on 51 statements into the SPSS programme.

In the first phase, simple descriptive statistics were used to analyse the respondent’s profile and exploratory factor analyses were run to tap the underlying dimensions of each construct. The reliability alphas were calculated for all the multi-item scales and their Cronbach Alphas were reported.

In the second phase of the data analysis, structural equation modeling (SEM) technique was used to examine the overall hypothesised model and specific hypotheses testing. The measurement scales of all major constructs were subjected to validation through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using AMOS 16.0. Comparison between the disaggregated multi-components to a traditional unidimensional measure were addressed.

The results of alternative model testing indicated that two exogenous constructs were best represented through disaggregated multi-component model for socio-oriented and concept-oriented family communication constructs. Having met all the measurement issues such as unidimensionality of construct, convergent and discriminant validity, a structural model was then analysed to determine the structural relationships between exogenous and endogenous variables within the revised model.

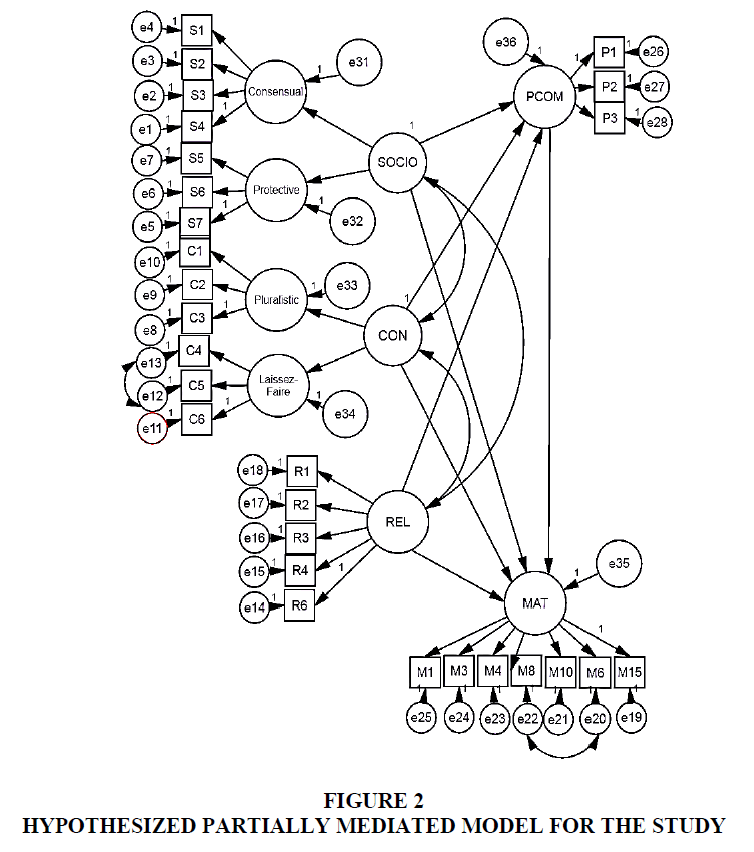

Based on CFA results, a second-order factor structure which contains two layers of latent constructs were drawn for this study. Variables socio-oriented family communication and concept-oriented family communication contained two layers of latent constructs. This study tested the proposed model fit to observed data using SEM technique. The hypotheses of this study were then tested.

The effects of socio-oriented, concept-oriented, and religiously-oriented family communications on materialism were tested. The effects of socio-oriented family communication, concept-oriented family communication, and religiously-oriented family communications on peer communication were tested. The effect of peer communication on materialism was tested.

The mediating effects of peer communication on the relationship between socio-oriented, concept-oriented, and religiously-oriented family communications on materialism were tested. The decomposition of direct, indirect and total effects of the hypothesized model was analysed. Following the hypotheses testing an evaluation of the final hypothesized structural model was made.

Research Practicalities and Results

Phase 1: Demographic Analysis

A descriptive analysis was conducted to summarize the demographic characteristics. A general profile of the respondents is discussed so that readers were able to gain a general idea of characteristics of the sample in this study. Second, the demographic information enabled the author to compare the sample characteristics (N = 956) with the population characteristics. The table frequency revealed that of the 956 respondents, who completed the questionnaire, 39.9% were males and 60.1% were females. This could be explained in terms of percentage of intake in public and private institution of higher learning where the percentage of female enrolment has the tendency to be higher in comparison to male (Ministry of Higher Education in Malaysia, 2010). In terms of age distribution, 63.6% of the samples were between the aged of 20-29 years old, followed by age range of 19 years old and below (25.4%) and the remaining of the respondents 11% were aged 30-40 years old. In terms of ethnic group, the majority of the sample consisted of Malay respondents (51.8%), followed by Chinese respondents (28.2%) and Indians (10.7%) and other ethnic groups formed (9.3%) of the sample. The respondent characteristic in terms of ethnicity was generally consistent with the Malaysian Population Census (Department of Statistics and Economic Planning Unit, 2008). In terms of education, the majority of the respondents in the sample group possessed a professional qualification/university degree (56.9%) and (32.2%) possessed a college diploma while 10.6% have obtained their high school certificate.

Phase 2: Confirming the Constructs

In this study, the author chooses to conduct exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and then confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) rather than directly conducting CFA. Hence, EFA was first performed separately on 37 statements. The purpose of performing factor analysis was to determine whether the data could be condensed or summarised into smaller set of factors (Malhotra, 2010).

The dimensions of the scales for socio-oriented family communication, concept-oriented family communication, religiously-oriented family communication, peer communication and materialism were examined by factor analysing the items using the principal components analysis with Varimax rotation.

Socio-oriented family communication consisted of 7 items measured on a Likert scale format and was a unidimensional construct. The results of the rotated factor matrix indicated that 3 significant items loaded on a factor, while another factor consisted of 4 significant items. The two factors representing the socio-oriented family communication construct accounted for 10.9% of the total variance. Both factor loading ranged from 0.588 to 0.792. Both subscales representing socio-oriented family communication construct were retained for subsequent analysis. The author followed the same procedure for the rest of the dimensions, which included concept- oriented family communication, religiously-oriented family communication, peer communication and materialism. For concept-oriented family communication two subscales representing concept-oriented family communication construct were retained for subsequent analysis as factor loading on each dimension had a higher value than 0.5. For religiously-oriented family communication construct, the results of rotated factor matrix indicated factor loadings of 5 significant item statements on the underlying construct with factor loading more than 0.5. The 5 items were retained for subsequent analysis. For peer communication construct, the results of rotated factor matrix indicated that the factor loadings contained three significant item statements, with factor loading more than 0.5. Following the same procedure for materialism construct which initially consisted of 15 items and was a unidimensional construct. Only 7 items were retained for further analysis.

Based on the results of the Principal Component Analysis (PCA), the reliability analysis and descriptive statistics for individual items of the socio-oriented family communication, concept-oriented family communication, religiously-oriented family communication, peer communication and materialism constructs displayed an acceptable degree of reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient ranging from 0.544 to 0.848. Pearson correlation was employed to examine the associations between the main constructs of the proposed model. Overall significant positive correlations were reported for all the hypothesized relationships at .01 level and .05 level of confidence in the expected direction.

One of the major challenges which the author faced at this point was to find theoretical justification and support from the literature for the emergence of these new dimensions before proceeding with further analysis. Looking back at the literature on family communication domain, the researcher found that these subscales reflected the typologies of family communication pattern The process of identifying supporting evidence was key to validate the model both theoretically and empirically. Fortunately, prior studies had established that family communication structures (socio-oriented family communication and concept-oriented family communication) were two relatively uncorrelated dimensions (Moschis & Mitchel, 1986). The socio-oriented family communication dimension produces deference and foster harmonious and pleasant social relationships. On the other hand, the concept-oriented emphasizes helping the child to develop his/her own individual views of the world by imposing positive constraints (Moschis & Mitchel, 1986).

Together, these two dimensions of family communication structure have produced a four-fold typology of family communication patterns: laissez-faire, protective, pluralistic, and consensual ( McLeod and Chaffee, 1972). According to Bakir et al. (2005), pluralistic parents emphasized low socio-orientation and high concept-orientation and encouraged their children to engage in overt communication and discussions. This communication pattern results in children that possessed independent perspectives and become skilled consumers. The literature was compatible with the findings derived from EFA results in the sense that each dimension corroborated with the four-fold typology of family communication patterns. Hence the author was able to proceed further in the analysis and conducted a CFA.

CFA Model Results

Gerbing and Anderson (1987) highlighted the importance of unidimensionality in the scale development process. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was employed for the assessment of measurement model fit and unidimensionality. In order to determine whether socio-oriented family communication, concept-oriented family communication, religiously-oriented family communication, and materialism, were best represented as single concept or multi-component constructs, confirmatory factor analysis was conducted.

The exploratory factor analysis results indicated that socio-oriented family communication and concept-oriented family communication produced two distinct components each; whilst religiously-oriented family communication, peer communication and materialism were found to be better modeled as a one-dimensional concept.

CFAs were employed to test and confirmed these findings as reported in the exploratory factor analyses. Following the exploratory factor analysis results, a disaggregated two-factor socio-oriented family communication measure was tested against a one-dimensional socio-oriented family communication concept to reflect the global socio-oriented family communication construct. Similar approach was used to test the concept-oriented family communication structure.

Based on empirical findings from factor analysis, this study found ground that the religiously-oriented family communication, peer communication, and materialism constructs were retained as a one-dimensional concept, whereas socio-oriented family communication structure and concept-oriented family communication structure were best represented through disaggregated multi-component concepts.

Prior to structural model testing, the construct validity and reliability were tested by checking the convergent validity, discriminant validity, and composite reliability of the data. The convergent validity was assessed by checking the loading of each observed indicators on their underlying latent construct. Other than fulfilling the factor loadings, the convergent validity assessment also included the measure of construct reliability and variance extracted. In this study, the variance extracted values for the main constructs exceeded the cut-off of 0.50 recommended by Fornell & Larcker (1981). Discriminant validity was determined by the variance extracted value. Overall, the required reliability and validity assessment demonstrated strong support for satisfactory convergent validity and discriminant validity. Hence, the subsequent process of identifying the structural model that best fits the data were conducted to test the proposed hypotheses.

Structural Equation Modelling (SEM)

This study adopted the SEM technique for the analysis of the integrated model of materialism. The use of SEM was deemed to be appropriate and it had several advantages over other multivariate analyses: (1) it took a confirmatory, rather than an exploratory approach to data analyses (Byrne, 2001); (2) the estimates were based on information from the full covariance matrix; (3) it was an easily applied method for estimating the direct and indirect effects (Davison et al., 2006); (4) SEM provided explicit estimates of the measurement error (Byrne, 2001); (5) SEM made it possible to analyse multiple structural relationships simultaneously while maintaining statistical efficiency (Hair et al., 2006); (6) SEM technique was considered a combination of both interdependence and dependence techniques, such that exploratory factor analysis and regression analysis could be conducted more comprehensively in one step (Hair et al., 2006); (7) SEM could incorporate both unobserved and observed variables into a model (Byrne, 2001). In addition to model fit testing, alternative model testing could be achieved with the use of SEM. Furthermore, the direct and indirect effects of all the predictors in the study could be estimated easily at once, as opposed to having to conduct a series of regression equations (Baron & Kenny, 1986).

The present study included the examination of potential mediating role of peer communication. Although mediation effect could be tested through a series of regression models, the use of two-stage approach and the ability to incorporate both unobserved and observed variables into a SEM model was considered to be a more superior approach (Hair et al., 2006). SEM approach provided explicit estimates of the measurement error (Byrne, 2001). An exploratory factor analysis was initially employed to purify the multi-item scale

Based on the theoretical and empirical justifications, the constructs of socio-oriented family communication, concept-oriented family communication, religiously-oriented family communication, peer communication, and materialism were subjected to confirmatory factor analyses using AMOS 16.0. Having met all the measurement issues such as unidimensionality of constructs, convergent and discriminant validity, the structural model was then analysed to determine the structural relationships between exogenous and endogenous variables within the revised model.

The current study tested the proposed model fit to observed data using SEM technique. The proposed model consisted of three exogenous constructs and two endogenous constructs. Research model testing and analyses were then conducted. To achieve goodness of fit for the empirical data, both the measurement and structural model had to meet the requirements of selected indices. The author believed that the sample size gathered for this study (N=956) was appropriate (Bentler & Chou, 1987), the chi-square normalised by degrees of freedom (χ²/df) was also used.

For the badness-of-fit index, RMSEA was chosen as it often provides consistent results across different estimation approach (Sugawara & MacCallum, 1993). Following this guideline, other than chi-square and normed χ²/df value, model fit for this study was examined using multiple indices which included Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and a badness-of-fit index, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) (Hu & Bentler, 1999). The SEM technique was used as the main statistical tool to test the main hypotheses proposed for this study. As suggested by Hair et al. (2006), the proposed theoretical model was modeled in a recursive manner to avoid problems associated with statistical identification. This was more so for the present empirical data that was cross-sectional in nature. There were a total of 28 indicators contained in the structural model. Each indicator was connected to the underlying theoretical construct in a reflective manner.

Following Kelloway’s (1995) recommendation, a sequence of tests was conducted to determine which model has the best overall fit to the empirical data. Competing model strategy (i.e, fully mediated model, partially mediated model and non-mediated model) was used to ensure that the hypothesized partially mediated model of peer communication not only has acceptable model fit, but also performed better than the alternative models (Hair et al., 2006). The result of competing model testing and hypothesized structural effects led to a proposal of a partially mediated model in which peer communication was modeled as a mediator between the predictor variables and the ultimate dependent variable (i.e., materialism).

Thus, the partially structural mediated model included: (a) paths from the family-oriented communication constructs to peer communication; (b) path from peer communication to materialism; (c) paths from the family-oriented communication to materialism; and d) correlation between the predictors. The hypothetical partially mediated model was depicted using visual tools provided by AMOS software. The partially mediated model model demonstrated a better model fit and was used as the final model for hypothesis testing (χ² = = 872.186, χ²/df = 2.611, GFI =0.939, TLI = 0.903, CFI = 0.915, RMSEA = 0.041).

Upon completing hypotheses testing, the proportion of variance explained by the proposed model was examined. The squared multiple correlations (R²) were examined to determine the proportion of variance that was explained by the exogenous constructs in the theoretical model. Specifically, the total variance in peer communication explained by the four consumer socialization constructs was 15.4% in the final model. The proposed model explained a substantial amount of variance in materialism in that all direct and indirect effects contributed to 14.4% of the total variance, which was considerably low. This could be attributed to the numerous factors that may affect materialism Table 1 Figure 2.

| Table 1 The Hypothetical Partially Mediated Model by AMOS Software | |||||

| Chi Square (χ2) | Ratio | GFI | TLI | CFI | RMSEA |

| χ2=872.186 d.f 334 (p=.000) | 2.611 | .939 | .903 | .915 | .041 |

Squared Multiple Correlations: 0.154 (peer communication); 0.144 (Materialism)

Note: SOCIO=Socio-oriented family communication, CON = Concept-oriented family communication, REL= Religiously-oriented family communication, PCOM= Peer communication, MAT= Materialism

Source: AMOS Graphic Output.

Challenges and Limitations

Inevitably, this study has its own limitations. In terms of theoretical limitation, it has been established that the family environment would impact on the development of materialism. However, parental influence is not limited to the family communication environment alone. Within the context of family environment, other important variables need considerable attention as well. This study has captured the effect of family communication environment on materialism, whereas the effect of family structure, and family resources were not examined in the model. Another objective of this study was to investigate the effect of peer communication would have an implication on the materialistic orientation of young adult consumers. This study has explored peer interaction effect but did not examined the nature and purpose of interactions (which could be in the form of normative versus informative) and the degree to which it may have an implication on the development of materialism among young adult consumers Table 2.

| Table 2 Summary of the Tests of Hypothesized Relationships | |

| Hypotheses Statements | Findings |

| H1: Young adult person’s exposure to a socio-oriented family communication structure at home during adolescent years is positively associated with their orientation towards materialism in their adulthood. | Supported |

| H2: Young adult person’s exposure to a concept-oriented family communication structure at home during adolescent years is negatively associated with their orientation towards materialism in their adulthood. | Not Supported |

| H3: Young adult person’s exposure to a religiously-oriented family communication structure at home during adolescent years is negatively associated with their orientation towards materialism in their adulthood. | Not supported |

| H4: Young adult person’s exposure to a socio-oriented family communication structure at home during adolescent years has a positive effect on peer communication. | Supported |

| H5: Young adult person’s exposure to a concept-oriented family communication structure at home during adolescent years has a positive effect on peer communication. | Supported |

| H6: Young adult person’s exposure to a religiously-oriented family communication structure at home during adolescent years has a positive effect on peer communication. | Supported |

| H7: Young adult person’s communication with their peers during adolescent years is positively associated with their orientation towards materialism in their adulthood. | Supported |

| H8: Peer communication mediates the relationship between young adults’ exposure to a socio-oriented family communication structure at home during adolescent years and their orientation towards materialism in their adulthood. | Supported |

| H9: Peer communication mediates the relationship between young adults’ exposure to a concept-oriented family communication structure at home during adolescent years and their orientation towards materialism in their adulthood. | Supported |

| H10: Peer communication mediates the relationship between young adults’ exposure to a religiously-oriented family communication structure at home during adolescent years and their orientation towards materialism in their adulthood. | Supported |

Methodological limitations may have also weakened to some extent the validity and generalizability of this research findings. This study has examined the influence of three major socialization agents influence on the orientation of materialism among young adult consumers and respondents of this study were asked to reflect back during their childhood years and were provided with a list of things that their parents did or said during their conversation with them.

Although most of the instruments employed in this study were reliable, respondents could have had some difficulties to recall back their family conversations and the list of things that parents sometimes said or did during their childhood while growing up. This is especially so due to the passage of time and life events from childhood to adulthood which could have affected their ability to retrieve information that took place in the past among family members and themselves accurately. As a result, the validity of the results could have been affected to certain extent.

Lastly, the findings of this study is limited to explaining the respondents in the current study since the survey employed a convenience student sample from public and private institution of higher learning in the Klan Valley in Malaysia. The use of a convenience sample may have led to a homogenous sample and the findings may not be generalizable to other settings or nations. It is therefore not appropriate to generalize the findings to all young adults or college students in Malaysia. However, they can serve as a good reference for future research.

Statements and Declarations

Funding

The author declares that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Competing Interests

The author has no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Research Data Policy and Data Availability Statements

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. The data collected is part of a survey conducted by the author for the purpose of this study.

References

Adib, H., & El‐Bassiouny, N. (2012). Materialism in young consumers: An investigation of family communication patterns and parental mediation practices in Egypt. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 3(3), 55-282.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bao, W.N., Whitbeck, L.B., Hoyt, D.R., & Conger, R.D. (1999). Perceived parental acceptance as a moderator of religious transmission among adolescent boys and girls. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61(2), 362-374.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Baron, R.M., & Kenny, D.A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bakir, A., Rose, G.M., & Shoham, A. (2005). Consumption communication and parental control of children’s television viewing: A multi-rater approach. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 13(2), 47-58.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Benson, P.L., Yeager, R.J., Wood, P.K., Guerra, M.J. & Manno, B.V. (1986). Catholic high schools: Their impact on low-income students. National Catholic Educational Association, 17(2), 7-19.

Benmoyal-Bouzaglo, S., & Moschis, G.P. (2010). Effects of family structure and socialization on materialism: A life course study in France. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 18(1), 53-70.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bentler, P.M., & Chou, C.P. (1987). Practical issues in structural modeling. Sociological Methods & Research, 16(1), 78-117.

Bollen, K.A. (1990). Overall fit in covariance structure models: Two types of sample size effects. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 256.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bristol, T., & Mangleburg, T.F. (2005). Not telling the whole story: Teen deception in purchasing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 33(1), 79-95.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Burroughs, J.E., & Rindfleisch, A. (2002). Materialism and well-being: A conflicting values perspective. Journal of Consumer Research, 29(3), 348-370.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Byrne, B.M. (2001). Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming.

Carlson, L., Walsh, A., Laczniak, R.N., & Grossbart, S. (1994). Family communication patterns and marketplace motivations, attitudes, and behaviors of children and mothers. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 28(1), 25-53.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Chaplin, L.N., & John, D.R. (2010). Interpersonal influences on adolescent materialism: A new look at the role of parents and peers. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 20(2), 176-184.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Chia, S.C. (2010). How social influence mediates media effects on adolescents’ materialism. Communication Research, 37(3), 400-419.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Churchill Jr, G.A. (1979). A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 16(1), 64-73.

Churchill Jr, G.A., & Moschis, G.P. (1979). Television and interpersonal influences on adolescent consumer learning. Journal of Consumer Research, 6(1), 23-35.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Costello, A.B., & Osborne, J. (2005). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 10(1), 7.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Cooper, D.R., & Schindler, P.S. (2003). Business Research Methods.

Davison, K.K., Downs, D.S., & Birch, L.L. (2006). Pathways linking perceived athletic competence and parental support at age 9 years to girls' physical activity at age 11 years. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 77(1), 23-31.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

DeMotta, Y., Kongsompong, K., & Sen, S. (2013). Mai dongxi: Social influence, materialism and china's one-child policy. Social Influence, 8(1), 27-45.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Department of Statistics and Economic Planning Unit. (2008). The Malaysian Economy in Figures 2008.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D.F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39-50.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Flouri, E. (1999). An integrated model of consumer materialism: Can economic socialization and maternal values predict materialistic attitudes in adolescents?. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 28(6), 707-724.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Gerbing, D.W., & Anderson, J.C. (1987). Improper solutions in the analysis of covariance structures: Their interpretability and a comparison of alternate respecifications. Psychometrika, 52(1), 99-111.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

John, D.R. (1999). Consumer socialization of children: A retrospective look at twenty-five years of research. Journal of Consumer Research, 26(3), 183-213.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hair, Jr., J.F., Black, W.C., Babin, B.J., Anderson, R.E., & Tatham, R.L. (2006). Multivariate data analysis, upper saddle river, new jersey, pearson prentice hall.

Hunsberger, B. (1985). Parent-university student agreement on religious and nonreligious issues. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 24(3), 314-320.

Hu, L.T., & Bentler, P.M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1-55.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Keng, K.A., Jung, K., Jiuan, T.S., & Wirtz, J. (2000). The influence of materialistic inclination on values, life satisfaction and aspirations: An empirical analysis. Social Indicators Research, 49(3), 317-333.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kelloway, E.K. (1995). Structural equation modelling in perspective. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 16(3), 215-224.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

King, P.E., Furrow, J.L. and Roth, N. (2002). The Influence of families and peers on adolescent religiousness. Journal of Psychology and Christianity, 21, 109-120.

La Ferle, C., & Chan, K. (2008). Determinants for materialism among adolescents in Singapore. Young Consumers, 9(3), 201-214.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Malhotra, N.K. (2010). Marketing research: An Applied orientation, upper saddle river, New jersey, Prentice hall.

McLeod, J.M., & Chaffee, S.R. (1972). The construction of social reality. In the Social Influence Processes, 50-99.

Ministry of Higher Education in Malaysia. (2011). Statistics on Enrolment.

Moschis, G.P., & Churchill Jr, G.A. (1978). Consumer socialization: A theoretical and empirical analysis. Journal of Marketing Research, 15(4), 599-609.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Moschis, G.P., & Mitchell, L.G. (1986). Television advertising and interpersonal influences on teenagers' participation in family consumer decisions. ACR North American Advances.181-186.

Moschis, G.P., & Moore, R.L. (1979). Family communication and consumer socialization. ACR North American Advances.

Moschis, G.P., & Moore, R.L. (1979). Decision making among the young: A socialization perspective. Journal of Consumer Research, 6(2), 101-112.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Moschis, G.P., Hosie, P., &Vel, P. (2009). Effects of family structure and socialization on materialism: A life course study in malaysia. Journal of Business and Behavioural Sciences, 21(1), 166-181.

Moschis, G.P., Moore, R.L. (1982). A longitudinal study of television advertising effects. Journal of Consumer Research, 9(3), 279-286.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Moschis, G.P., Moore, R.L., & Smith, R.B. (1984). The impact of family communication on adolescent consumer socialization. Advances in Consumer Research, 11, 314-319.

Moschis, G.P., Ong, F.S. (2011). Religiosity and consumer behaviour of older adults: A study of subcultural influences in malaysia. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 10(1), 8–17.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Moschis, G.P., Mathur, A., Fatt, C.K., & Pizzutti, C. (2013). Effects of family structure on materialism and compulsive consumption: A life course study in Brazil. Journal of Research for Consumers, 23(4), 66-96.

Moore, R.L., Moschis, G.P. (1981). The effects of family communication and mass media use on adolescent consumer learning. Journal of Communication, 31, 42-51.

Myers, S.M. (1996). An interactive model of religiosity inheritance: The importance of family context. American Sociological Review, 61(5), 858- 866.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Myers, L.S., Gamst, G., Guarino, A.J. (2006). Applied mutivariate research: Design and Interpretation. Sage Publication, 513- 517.

Potvin, R.H., Sloan, D.M. (1985). Parental control, age, and religious practice. Review of Religious Research, 27(1), 3-14.

Rindfleisch, A., Burroughs, J.E., Denton, F. (1997). Family structure, materialism, and compulsive consumption. Journal of Consumer Research, 23(4), 312-325.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Rotfeld, H.J. (2003). Convenient abusive research. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 37(1), 191-194.

Santos, C.P., Fernandes D. (2011). Consumption socialization and the formation of materialism among adolescents. Revista de Administração Mackenzie, 12(1), 169-203.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Shi, B., & Xie, H. (2013). Peer group influence on urban preadolescents' attitudes toward material possessions: Social Status Benefits of Material Possessions. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 47(1), 46-71.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Shu-Chuan, C., Kamal, S., Morrison, M. (2012). Culture, social media intensity, and materialism: A comparative study of social networking, microblogging and video sharing in china and the United States. American Academy of Advertising Conference Proceedings, 99-99.

Shrum, L.J., Lee, J., Burroughs, J.E., & Rindfleisch, A. (2011). An on- line process model of second-order cultivation effects: How television viewing cultivates materialism and its consequences for life satisfaction. Human Communication Research, 37(1), 34-57.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Staub, E. (1988). The evolution of caring and non-aggressive persons and societies. Journal of Social Issues, 44(2), 81-100.

Sugawara, H.M., & MacCallum, R.C. (1993). Effect of estimation method on incremental fit indexes for covariance structure models. Applied Psychological Measurement, 17(4), 365-377.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Vega, V., Donald, F., & Roberts, D.F. (2011). Linkages between materialism and young people’s television and advertising exposure in a US sample. Journal of Children and Media, 5(2), 181-193.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ward, S., Wackman, D.B., & Wartella, E. (1977). How children learn to buy: The development of consumer information-processing skills. Sage.

Wilson, J. and Sherkat, D.E. (1994). Returning to the Fold. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 33(2), 148-161.

Wong, N., Rindfleisch, A., & Burroughs, J.E. (2003). Do reverse-worded items confound measures in cross-cultural consumer research? The case of the material values scale. Journal of Consumer Research, 30(1), 72-91.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Received: 26-Dec-2022, Manuscript No. AMSJ-22-13045; Editor assigned: 27-Dec-2022, PreQC No. AMSJ-22-13045(PQ); Reviewed: 10-Jan-2023, QC No. AMSJ-22-13045; Revised: 11-Jan-2023, Manuscript No. AMSJ-22-13045(R); Published: 12-Jan-2023