Research Article: 2021 Vol: 25 Issue: 6

Socially Responsible Marketing and Brand Switching behaviour: Insights from Fmcg Industry During Covid 19 Pandemic

Ram Kishen Yelamanchili, KJ Somaiya Institute of Management

Karthik Rajagopal, KJ Somaiya Institute of Management

Aparna Jain, SK Somaiya College

Bharati Wukadada, KJ Somaiya Institute of Management

Citation: Yelamanchili., R.K., Rajagopal, K., Jain, A., & Wukadada, B. (2021). Socially responsible marketing and brand switching behaviour: insights from fmcg industry during covid-19 pandemic. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 25(6), 1-13.

Abstract

The onset of Covid-19 resulted in widespread panic and distress among the people, which pushed businesses to change their marketing and communication strategies. Various brands launched socially responsible marketing campaigns aimed at supporting the communities affected by the Covid-19 pandemic. The existing studies on this subject conclude that adding a humanitarian layer to the communication strategy for brands will strengthen the brands and build loyalty. More importantly, this will also convince consumers to purchase during this uncertain phase. Cause-related campaigns have shown a significant impact on consumer’s buying decisions in the past. This research study attempts to understand how effective these campaigns were in persuading consumers to switch brands and identifies three groups of consumers based on the factors that triggered a brand switch. For an in-depth understanding brands, the Fast-Moving Consumer Goods (FMCG) sector was chosen for this research study. A structured questionnaire was administered to individual respondents in Mumbai city, to understand their attitude towards four various social marketing campaigns, each representing a product category. The results of the analysis revealed that consumers were open to switching brands due to these marketing campaigns. Moreover, these campaigns also impacted the repurchasing behavior among consumers. It was also found that a brand-NPO(Not for Profit Organizations) partnership had a significant impact on influencing consumers to switch brands.

Keywords

Responsible Marketer, Social Marketing, Cause-Related Marketing, Brand Preferences, Brand Switching Behavior, Brand Loyalty, India.

Introductions

The year 2020 saw communities, businesses, and economies transform due to a viral pandemic that brought the human race to a standstill. The onset of covid-19 led to unrest in the business world, with companies of all scales attempting to find different ways and means to survive the impact caused by the viral outbreak. The World Bank (2020) states how people were involved in panic buying essential goods in the light of various countries imposing lockdowns that brought lives to a standstill. There was a change in the emotions felt by people. Kumar and Dutt (2020) point out this change in consumers' buying behavior, which meant that the marketers had a task cut out in front of them. Communicating with the consumers during such unprecedented times is an uphill task for any brand. People sought support, and there was a sharp change in the way brands conversed with the outer world. MoEngage (2020) depicts how brands like Oyo, Zoomcar and Tata Health spread positive messages and supported people differently.

In all, there was a sense of social responsibility in the way brands communicated to the masses. This aspect of social responsibility was very different from what brands had displayed during regular times. Mckinsey & Company's (2020) article highlights how companies had even shifted production to manufacture medical equipment and demonstrate purpose in their efforts. Social responsibility was no more playing second fiddle. There was an increased need to tell the customer, "We care for you and the people around you."

Various brands across product categories, ranging from Bose to Burger King, incorporated social messages in their campaigns, as stated by the Financial Times (2020). These campaigns were presented with a forward-looking tone. One can thus observe that responsible marketing was prevalent during the covid-19 pandemic. Socially responsible marketing is a broad term covering various related marketing concepts, as Vaaland et al. (2008) stated. Out of all the concepts, social marketing and cause-related marketing (CaRM) are primarily being considered for this study. Akter and Hossain (2020) define social marketing as a systematic process of influencing behavior change of different target market segments by utilizing a planning process that uses marketing principles and tactics to deliver positive societal benefits.

Another tangent to responsible marketing is cause-related marketing, which Chaudhary and Ghai (2014) believe is a concept that helps differentiate a brand from its competitors. Pandukiri et al. (2017) define it as a novel idea through which companies can increase their sales while focusing on social responsibility. Varadharajan and Menon (1988) define cause-related marketing as the process of formulating and implementing marketing activities characterized by an offer from the firm to contribute a specified amount to a designated cause when consumers engage in revenue-providing exchanges that satisfy organizational and individual objectives. Marketing campaigns such as those stated above would have impacted the consumers' perceptions in different ways. This explorative study aims to understand if these campaigns can effectively make consumers switch brands during the pandemic. For the study, four campaigns, each in a different product category, were selected. These campaigns were released during the time of covid-19. A questionnaire was administered to understand the respondents’ inclination towards switching to a new brand after watching the campaigns. The research further attempted to identify the factors that played a significant role in influencing consumers to switch brands and categorized them based on the factors that impacted their decision.

Literature Review

Mathur & Priya (2020) studied the ongoing pandemic's impact on marketing and concluded that brands would be forced to re-think their plans due to the changing consumer behavior. This is primarily because of the shift towards responsible and prosocial consumption, as He and Harris (2020) believe, while consumers will also constantly reflect on their brand choices to be more responsible towards themselves and society. Finally, Akter and Hossain (2020) analyzed the impact of programs aired in Bangladesh to spread awareness about WHO-directed behaviors and called for well-planned social marketing intervention programs by private and non-profit organizations as directed by the government. Responsible marketing campaigns have been leveraged in the past during a global pandemic, as demonstrated in Jones and Iverson's (2012) study on how effective social marketing can tackle pandemic influenza such as the avian flu. Kotler et al. (2002), as cited in Jones and Iverson (2012), enlisted a few elements for a successful social marketing campaign, such as communicating a simple, doable behavior, incorporating and promoting a tangible object or service to support the target groups. In the case of covid-19, it can be the usage of a mask or a hand sanitizer. Mathur and Priya (2020) add to this idea that adding a humanitarian layer to brand communication will also help persuade consumers to buy during uncertain times.

Studies about social marketing date back to the late 20th century. Keller (1998) describes how brands can be created with social marketing by employing various tactics such as multiple brand elements (logos, symbols, characters, packaging, slogans, etc.), creating sub-brands, IMC campaigns, etc. Cause-Related Marketing has gained importance over time because it affects brand preferences, as Bina and Priya (2014) identified. A similar insight is given by Punjani (2016) through his attempt to examine the influence of social advertising campaigns of FMCG companies on consumer behavior. He demonstrated that consumers are highly aware of the CSR initiatives by companies, and these cause-related activities also have a significant impact on the buying decision of the consumers. The impact of social marketing can be extended to brand preferences, as seen in Bina and Priya (2015). The authors established four significant attributes that consumers resonated with while purchasing a brand that supports a cause. They were the feel-good factor (association with the brand), self-reference (self's response towards the messages), action factor (inclination to buy these brands), and self-connect (emotions towards brands that support a social cause). Singh (2016) explored the connection between cause-related marketing and brand preferences and concluded that CRM could lead to non-users of brands switching to a new brand.

Today, various brands are engaging Indian consumers in cause-related marketing campaigns, and sometimes, these campaigns also have commercial motives. Chaudhary and Ghai (2014) comment that in a highly competitive sector like Fast Moving Consumer Goods (FMCG), where various brands' prices and quality are par with each other, cause acts as a differentiator. Rajput et al. (2013) also extend the same observation and further reveal that consumers specifically ask for brands that support a social cause. Many of the studies mentioned above have confirmed that social cause-related marketing significantly impacts brand preference, and this study also follows suit. Chaudhary and Ghai (2014) also discuss the importance of targeting India's youth with cause-related campaigns because of their increasing buying power. They propose that relevant social marketing campaigns could influence young consumers to switch to a different brand, even if they belong to a medium-income group. On the other hand, Gill and Raina (2015) concluded that millennials are aware of cause-related marketing as a concept and are also mindful of the brands involved in such campaigns. Therefore, these marketing activities lead to increased brand awareness, affecting millennials' purchase intentions. Eastman et al. (2018) offered an extended perspective that the millennials’ purchase intentions resulting from cause-related campaigns could be different for different products. Despite being aware of cause-related marketing, millennials are not very aware of the donation recipient in the alliance. Human and Terblanche (2015) identified that firms could enjoy success with CaRM despite the lack of awareness about the donation recipient. Alcaniz et al. (2010) had earlier presented a different angle to this aspect, concluding that company-customer (C-C) identification can generate positive behavioral responses to CaRM. When the customer feels involved with the cause, C-C alignment on purchase intention is amplified.

Various factors influence a consumer’s feeling towards a campaign, as depicted by Sindhu (2020). Factors such as consumer’s consciousness for the cause (feelings for the cause), subjective norms (perception of consumers regarding the social pressure to buy the product), consumer’s knowledge of operation procedure (details about operations of the campaign, donation transfer to beneficiary, etc.) and type of cause (could be related to education, environment, marginalized communities or something that needs immediate attention like a natural disaster) have strong driving power to influence consumers’ personal feelings about a campaign.

Theoretical Model

The theory of reasoned action (TRA) proposed by Ajzen & Fishbein (1980) and Fishbein & Ajzen (1975) serves as a base for this study. Studies in the past such as Choong (1998) and Julie (2005) applied TRA to study marketing concepts such as brand loyalty and consumer motivation. TRA has also been used by Linda et al. (2011), Ogenyi and Nana (2007) and Francis and Bungkwon (1996) to study the consumer attitude and behavioral intention in areas such as green consumption, insurance and hotel management. In addition, this theory has been applied in Hyllegard et al.'s (2010) study about the influence of gender, social cause, etc., on Gen Y’s responses to cause-related marketing. According to this theory, an individual’s intention to engage in a behavior is considered the best predictor of whether or not the individual will engage in it. The intention is a result of the individual’s attitude and subjective norms. In this study, this theory explains the consumers’ inclination to switch brands after watching a social marketing campaign. If a respondent confirms an intention to switch brands, it is predicted to happen. Drawing inferences from literature and the theory mentioned above, the following hypotheses have been formulated:

H1: Socially responsible marketing significantly influenced the consumers’ brand switching behavior during covid times.

H2: Socially responsible marketing significantly influenced the repurchasing behavior of consumers during covid times.

H3: Socially responsible marketing significantly influenced the consumer behavior towards Brand-NGO partnership during covid times.

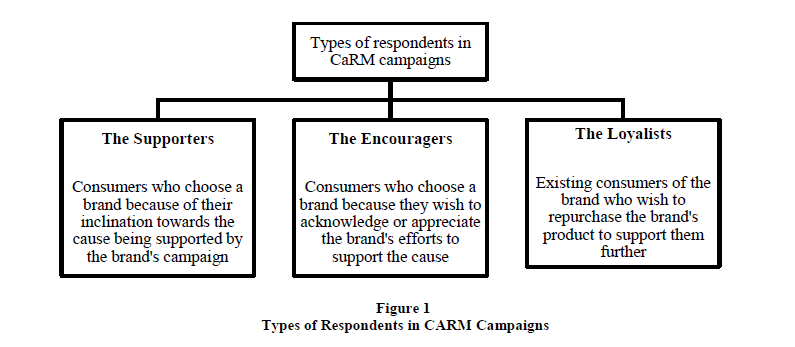

The study also intends to identify different groups of respondents towards cause-related marketing campaigns and understand each type of group in the community. The proposed groups are as follows in Figure 1.

Research Methodology

A structured questionnaire was administered via an online link to 250 respondents based in Mumbai. Out of the 250, around 200 respondents shared their responses on a set of given questions about four social marketing campaigns, each in a different product category. The convenience sampling method was used for data collection, considering the restrictions on movement due to the pandemic. Previous studies on understanding consumer behavior towards cause-marketing campaigns such as Punjani (2019) and Pandukiri et al. (2017) have used the convenience sampling method.

The questionnaire had five sections: A general section to understand the sample set's awareness levels concerning social cause-related marketing and how it influences their buying decision. The statements given as options in each question were based on previously validated studies such as Punjani (2019) and Sindhu (2020). Next, Likert Scales were used to understand the inclination of the consumers towards switching brands. A value of 3 and above in the scale indicates an inclination to switch. The following four sections consisted of the campaigns launched by the brands mentioned below in Table 1. At the beginning of each section, the respondents were also asked to share their current brand choice in each category to analyze brand switches later. The next phase of the research involved using statistical tools such as SPSS and MS Excel to analyze the responses and run tests to verify the hypotheses.

| Table 1 Details of Campaigns used in the Study |

|||

| Brand | Category | Campaign Title | Partner NPO |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dove (Shampoo) | Personal Care | Courage is Beautiful | Direct Relief |

| Savlon (Handwash) | Personal Hygiene | No Hand Unwashed | Mouth and Foot Painters Association |

| Ghadi (Detergent) | Laundry | Bachaav Mein Hi Samajhdaari Hai |

Not Applicable |

| Lay's (Potato Chips) | Snacks | Heartwork | Smile Foundation |

The brands were chosen based on their market share and involvement in responsible marketing campaigns. The chosen brands constitute a mix of market leaders and market challengers. As per the Economic Times (2015 and 2016) reports, HUL dominated the shampoo market in India in 2016 with a 48.8% share. Their brands Clinic Plus and Dove were the significant contributors in the same order. The next brand, Savlon, was reported to have a market share of 6.1 % by the Times of India (2017), while Dettol dominated the handwash category with more than 50% of the share. Sourav (2019) reported Ghadi Detergent's market share in the volume detergent segment to be 17.3 %, with HUL's Wheel lagging at 16.9%. Brands like Ariel and Surf Excel are a part of the premium segment. Business Today (2019) reported the volume share of Lay's to be 33% in 2019.

A one-sample t-test was run on SPSS to identify the factors that significantly impacted buying decisions. A paired t-test was used to compare the means of ‘likeliness to switch brands because a brand supports social cause’ before and after the respondents had watched each of the four campaigns. A one-Sample t-test was then used again to test the hypothesis on consumers’ inclination towards switching brands. Further, an independent sample t-test was run to understand if there exists a difference in the likeliness of the current brand users and non-users to switch brands after watching the campaigns. Researchers have used these tests to study consumer aspects such as purchase behavior and response to CaRM. Singh (2018) and Raina and Nandakumar (2013) used the one-sample t-test to study the response of Indian millennials and students to CaRM, respectively. An independent sample t-test was used by Boenigk and Schuchardt (2013), while Cui et al. (2003) used a combination of independent sample t-test and paired sample t-test in their studies about CaRM.

Finally, based on the consumers’ responses to why they were inclined to switch to a new brand, they were categorized into three groups in Table 2.

| Table 2 Customer Groups Based on their Motivation to Switch Brands |

|

| Group | Corresponding Items |

|---|---|

| The Supporters |

|

| The Encouragers |

|

| The Loyalists |

|

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Demographic Profile

75.5% of the respondents are 24-29 years old, while the rest, 24.5%, are 18-23 years old. The sample set consists of 45.5% male respondents and 54.5% female respondents. 80% of the respondents had stated that they had seen FMCG brands share advertisements with a social message after March 2020, when a nationwide lockdown was implemented to prevent the viral spread. These respondents were also able to recall brands that had launched such advertisements. The prominent brands recognized were Dabur, Coca-Cola, Nestle (Maggi), Cadbury's, ITC and HUL.

One-Sample T-Test: Importance of Various Factors Involved In buying Decisions

The respondents were also asked to rate the importance they give to various factors while purchasing a product, and the results were analyzed using a one-sample test on SPSS in Table 3.

| Table 3 Results of One-Sample T-Test |

|||

| Test Value = 3 | |||

| Factors | Sig. (2-tailed) | Mean | |

| Importance (Price) | .000 | 3.88 | |

| Importance (Attractive Packaging) | .604 | 3.04 | |

| Importance (Brand Ambassador) | .000 | 2.22 | |

| Importance (Social cause supported by the brand) | .000 | 3.30 | |

| Importance (Social messages in Ads) | .548 | 3.04 | |

Here, a p-value of less than 0.025 would be considered significant. Therefore, we can conclude that price, brand ambassador, and social cause supported by the brand are the factors that significantly impact the buying decision. Further, price and social cause have a mean value of more than 3, indicating that buyers prioritize these factors when making their purchase decisions. On the other hand, the mean for Brand Ambassador is 2.22, which implies that buyers do not consider this an essential factor. In addition to the above, 74.5% of respondents stated that they had preferred and bought a brand because it supported a social cause Table 4.

| Table 4 Results of Paired T-Test |

||||

| Difference in Means | Standard Deviation | Sig. (2 tailed) | Cohen’s D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pair 1 (Dove) | 0.270 | 1.036 | 0.000 | 0.26 |

| Pair 2 (Savlon) | 0.335 | 0.979 | 0.000 | 0.34 |

| Pair 3 (Ghadi) | 0.840 | 0.969 | 0.000 | 0.87 |

| Pair 4 (Lay’s) | -0.055 | 1.067 | 0.467 | 0.05 |

Paired T-Test and Cohen’s D

We can infer that the means for ‘switching brands in general because of a brand’s support towards a social cause’ and the likeliness to switch to each of Dove, Savlon and Ghadi Detergent differ statistically significantly (because their p < 0.05). To further understand the extent of the difference, we used Cohen’s D, and the above values imply a small effect size for Pairs 1 and 2 and a large effect size for Pair 3. As far as Pair 4 is concerned, there is no statistically significant difference in the means, and Cohen’s D also indicates the same.

One-Sample T-Test

A one-sample t-test was run to analyze the consumers’ inclination towards switching brands, and the results were as follows in Table 5.

| Table 5 Results of One-Sample T-Test |

||

| Test Value = 3 | ||

| Campaign | Sig. (2-tailed) | Mean |

| Dove | .000 | 3.25 |

| Savlon | .011 | 3.19 |

| Ghadi | .000 | 2.68 |

| Lay’s | .000 | 3.58 |

Here, a p-value of less than 0.025 would be considered significant. Hence, all four campaigns are statistically significant. Further, to understand if the consumers are inclined to switch brands, we consider the mean values. The campaigns by Dove, Savlon and Lay’s have a mean value above 3, indicating the consumer’s inclination to switch to those brands after watching the campaign, thus proving the first hypothesis. On the other hand, the mean for Ghadi Detergent is under 3, indicating the consumers’ low inclination towards switching to Ghadi Detergent due to its campaign. Hence, we reject the first hypothesis for Ghadi Detergent. This test was conducted by considering all the respondents, i.e., the users and non-users of the campaign brands. Therefore, we explored the responses of these two groups to identify further insights.

Independent Sample T-Test

We used an independent sample t-test to understand if the campaigns impacted the repurchasing intentions of consumers and if there is a difference in the inclination levels of the current users and non-users of each of the four campaign brands to switch brands after being exposed to the campaigns in Table 6.

| TABLE 6 Results of Independent Sample T-Test |

|||||||||

| Dove | Savlon | Ghadi | Lay’s | ||||||

| Levene’s Test (Sig.) | 0.126 | 0.434 | 0.001 | 0.067 | |||||

| t-Test (Sig.) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |||||

| Dove | Savlon | Ghadi | Lay’s | ||||||

| User (Mean) | 3.56 | 4.32 | 3.00 | 3.93 | |||||

| Non-User (Mean) | 3.08 | 3.07 | 2.68 | 3.05 | |||||

| t value | 3.461 | 5.414 | 0.001 | 6.091 | |||||

The p values given by Levene’s test for equality in variances indicate equal variances for Dove, Savlon and Lay’s as their p values are greater than 0.005. We assume unequal variances for Ghadi Detergent. Further, the p values given by the t-test indicate a significant difference (as all p values are lesser than 0.001) in the purchasing intentions of the current users and non-users of all four brands. The positive t value indicates the higher mean value of the ‘users’ group, which implies that the campaigns had a significant impact on repurchasing decisions, thus proving the second hypothesis. These values lead to the following inferences when interpreted by considering the market position of the brands.

- Dove - A mean of 3.56 for the users implies that they are inclined towards repurchasing Dove products. On the other hand, the mean for non-users is also above 3, indicating an inclination to switch. This results from two-thirds of the non-users having chosen a value of 3 and above in response to their likeliness to switch.

- Savlon - A mean of 4.32 for the users shows a strong inclination towards rebuying Savlon handwash. On the other hand, the mean for non-users is also above 3. Though it is slightly higher than the test value, a breakup of the responses revealed that 60.8% of the non-users had chosen a value of 3 or above. Considering Savlon’s market share, this campaign could boost their chances of improving their share against the likes of Dettol.

- Ghadi Detergent - From the values given in the above tables, it is inferred that the campaign didn't substantially impact the consumers. The non-users are not inclined to switch to Ghadi Detergent, with more than half of the sample indicating a low inclination to switch.

- Lay’s - A mean of 3.93 for the users shows a strong inclination towards rebuying Lay's. On the other hand, the mean for non-users is just above 3, depicting a decent inclination to switch brands. This can be linked with 70% of the non-users having chosen a value of 3 and above. As Lay's is a leader in this category, this campaign could help them further dominate the market.

Factors impacting the switching decision

People who were inclined to switch brands (rating of 3 and above after watching the campaign) were asked what motivated them to decide. The following were observed in Table 7.

| Table 7 Share of Factors Impacting Switching Decision |

||||

| Factors | Dove | Savlon | Ghadi | Lay’s |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| To show that I believe in the exact cause | 6.6 % | 4.1 % | 19.8 % | 2.4 % |

| To acknowledge the efforts of the brand | 14.6 % | 11.6 % | 28.1 % | 12.4 % |

| To contribute to the partner NGO (Dove, Savlon and Lay’s) To contribute to the cause (Ghadi) |

21.2 % | 32.0 % | 15.6 % | 22.0 % |

| To appreciate the initiative taken by the brand | 27.8 % | 36.7 % | 29.2 % | 16.5 % |

| I am an existing consumer. I'll buy again to support them further | 29.8 % | 15.0 % | 6.3 % | 46.3 % |

| None of the above | 0.0 % | 0.7 % | 1.0 % | 0.6 % |

Based on the categorization basis stated in the methodology and the numbers observed above, the respondents can be grouped as follows in Table 8.

| Table 8 Share of Customer Groups based on their Response to Campaigns |

||||

| Group/Campaign | Dove | Savlon | Ghadi | Lay’s |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Supporters | 27.8 % | 36.1 % | 35.4 % | 24.4 % |

| The Encouragers | 42.4 % | 48.3 % | 57. 3 % | 28.9 % |

| The Loyalists | 29.8 % | 15.0 % | 6.3 % | 46.3 % |

‘The Encouragers’ emerge as the most dominant group in three out of the four campaigns. However, in Dove and Lay’s campaigns, ‘The Loyalists’ have taken up a significant share, implying that a cause-related marketing campaign can have a loyalty-building effect on its existing consumers.

Discussion

The one-sample t-test indicates that consumers are open to buying a different brand in the personal care, handwash, and chips categories after watching the campaigns. Therefore, the first hypothesis is accepted for these categories. The significant level of inclination shown by the respondents to switch brands validates Mathur and Priya's (2020) argument about the inclusion of a humanitarian layer in the brand communication leading to persuading consumers to buy can help the marketers. The research also supports Bina and Priya's (2015) findings that social marketing impacts brand preferences. The study also upholds Chaudhary and Ghai's (2014) and Gill and Raina's (2015) conclusions that social marketing campaigns could increase brand awareness and influence young consumers and millennials to switch brands. Further, it also widens the geographic scope of Babu et al. (2008) that cause-related marketing influenced purchasing behavior of customers in Bangladesh. It can also be observed that the existing consumers of Dove, Savlon and Lay’s responded to the campaigns affirmatively and expressed their inclination to buy more. The values obtained in the independent sample t-test establish that the campaigns had a significant impact on the repurchasing behavior of the existing consumers, thus proving the second hypothesis. This observation strengthens the link between cause-related marketing and brand loyalty established by Brink et al. (2006). On the other hand, it also differs from the study by Hanzee et al. (2018), who concluded that there is no significant difference regarding the effect of cause marketing and CaRM on loyalty and repurchase intentions. This study, however, has identified CaRM to have a significant impact on repurchasing behavior. In addition to the above, the results depict the respondents’ inclination to buy a different brand to appreciate the brand’s initiative. This factor is among the top two factors that enabled a brand switching decision in the mind of the non-users across all product categories. Consumers also found these initiatives as a tool to contribute to a social cause or an NGO. This factor has also played a significant role in pushing the non-users to buy a different brand. In Dove, Savlon and Lay's campaigns, we can see that the brands' partnership with an external organization to support a community in need has emerged as one of the top 2 factors that made the non-users think about buying a different brand. This observation substantiates Felix et al.’s (2015) finding that consumers have a higher purchase towards campaigns with a cause-related marketing component than one without it. The responses to Ghadi Detergent's campaign strengthen this observation further. There was no external partnership involved in Ghadi Detergent’s campaign, and the majority have not considered this factor a significant driver that enabled them to switch brands. To sum it up, responsible marketing campaigns by leading brands such as Dove and Lay's will help them build loyalty. On the other hand, for brands like Savlon and Ghadi Detergent, which fight for share against dominant players, their campaigns could act as a competitive edge in the short term.

Theoretical and Managerial Implications Of The Research

This study supports the existing literature on the theory of reasoned action. The respondents’ inclination to switch brands acts as the best predictor of that event’s occurrence, and it is further validated by their response to which factor enabled their switching behavior. The study also contributes to the literature on CaRM by identifying three groups of consumers – the supporters, the encouragers and the loyalists, based on their reasons to support a CaRM in the middle of a pandemic. A significant proportion of the population is ready to purchase a brand to acknowledge or appreciate the efforts taken by a brand to support a social cause. These ‘Encouragers’ form a potential target segment for the marketers to widen the brand’s existing consumer base. On the other hand, it is crucial to strike the right chord with the target group using the planned campaigns as a marketer. Managers could use the following insights from this research when planning responsible marketing campaigns. First, buyers see marketing campaigns as a way of contributing to a cause or an NGO. Therefore, marketers should look to bring about a tangible change using the campaign and not simply spread a message. The consumers better receive campaigns that contribute to a community or an NGO. In trying times, such partnerships will prove effective and build a positive brand image in the buyer's minds. Second, marketers of brands that have not forayed into this arena need to consider the consumers' sentiments and start showing that they are socially responsible. Consumers are ready to acknowledge such efforts and even purchase their products to appreciate such initiatives. The example of Lay's is a testimony to how cause-related marketing campaigns can create ripples and enhance the brand's image. Third, brands challenged by dominant, established brands in their categories can leverage responsible marketing to gain a competitive edge. In addition, a meticulously crafted campaign can further help them sustain the new consumers. And fourth, the brands considered for this study could use the results to analyze their campaigns' effectiveness.

Conclusion

This research was conducted when brands across sectors went out of their ways to be more empathetic with the audience. Therefore, the authors can study if responsible marketing campaigns impact customers’ brand switching behavior when the world is free from the pandemic. Moreover, this study was aimed at only the FMCG sector. It can further be extended to other industries such as automobiles, financial services, etc., to get a holistic understanding of how these marketing campaigns impact customer buying behavior. The authors could build specific constructs for the three groups of consumers and understand their characteristics in-depth. The brand switching decisions gauged in this study could be short-lived because the consumers didn’t get to try their new preferred brand. An exhaustive study could be carried out to understand if the social cause is a solid factor to sustain the loyalty of the respondent for the new brand. Such a study will give insights into the factors that will lead brands to have a long-lasting impact on consumers' buying decisions. Today's buyers are more aware of cause-related marketing and corporate social responsibility activities of the brands they buy. These campaigns and activities impact the buying behavior of the consumers if they are planned and executed effectively. The research revealed the different reactions to the campaigns launched by brands in four different FMCG categories. One can observe that in the covid era, consumers are open to appreciating brands' initiatives towards the betterment of society. Moreover, these responsible campaigns also positively impacted buying patterns. They influence people to think about switching brands, and in return, the consumers are also supportive of brands partnering with external organizations. Brands can utilize these insights while planning their marketing strategy. The pandemic has changed the dynamic of marketing, and it would be interesting to observe how brands will integrate sympathy and social message in their communication in the future.

References

- Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behaviour. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Babu, M. M., & Mohiuddin, M. (2008). Cause Related Marketing and Its Impact on the Purchasing Behaviour of the Customers of Bangladesh; An Empirical Study. AIUB Bus Econ Working Paper Series.

- Balakrishnan, R. (2015, December 02). Dove's meteoric rise from 30 to 4 in the 'Most Trusted Brands' list decoded. Retrieved from The Economic Times: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/doves-meteoric-rise-from-30-to-4-in-the-most-trusted-brands-list-decoded/articleshow/49995248.cms

- Besson, E. K. (2020, April 28). COVID-19 (coronavirus): Panic buying and its impact on global health supply chains. Retrieved from World Bank Blogs: https://blogs.worldbank.org/health/covid-19-coronavirus-panic-buying-and-its-impact-global-health-supply-chains

- Bina, T., & Priya, S. P. (2015). A Study on Social Cause Related Marketing and Its Impact on. International Journal of Innovative Science, Engineering & Technology, 65-77.

- Boenigk, S., & Schuchardt, V. (2013). Cause-related marketing campaigns with luxury firms; AN experimental study of campaign characteristics, attitudes, and donations. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 101-121.

- Brink, D. v., Odekerken-Schroder, G., & Pauwels, P. (2006). The effect of strategic and tactical cause-related marketing on consumers' brand loyalty. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 15-25.

- Buttle Bungkwon Bok, F. (1996). Hotel marketing strategy and the theory of reasoned action. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 5-10.

- Choudhary, M., & Ghai, S. (2014). PERCEPTION OF YOUNG CONSUMERS TOWARDS CAUSE. International Journal of Sales & Marketing, 21-26.

- COVID-19 Regular Updates: The Business Impacts, Brands’ Responses, Marketing Strategies, and More. (2020, November 18). Retrieved from MoEngage: https://www.moengage.com/blog/covid19-updates-for-businesses/

- Craven, M., Liu, L., Mysore, M., & Wilson, M. (2020). COVID-19: Implications. Mckinsey & Company.

- Cui, Y., Trent, E. S., Sullivan, P. M., & Matiru, G. N. (2003). Cause-related marketing: how generation Y responds. International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management, 310-320.

- Debbie, H., & Terblanche, N. S. (2015). Who Receives What? The Influence of the Donation Magnitude and Donation Recipient in Cause-Related Marketing. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 141-160.

- Eastman, J. K., Smalley, K. B., & Warren, J. C. (2019). The Impact of Cause-Related Marketing on Millenials' Product Attitudes and Purchase Intentions. Journal of Promotion Management.

- Ejye Omar, O., & Owusu-Frimpong, N. (2007). Life Insurance in Nigeria: An Application of the Theory of Reasoned Action to Consumers' Attitudes and Purchase Intention. The Services Industries Journal, 963-976.

- Enrique Bigne, A., Rafael Curras, P., Carla Ruiz, M., & Silvia Sanz, B. (2010, July 7). Consumer behavioural intentions in cause-related marketing. The role of identification and social cause involvement. Springer-Verlag, pp. 127-143.

- Felix, R., Zadeh, A. H., & Baruca, A. (2015). Because It Makes Me Feel Good: Moderation and Mediation Effects in Cause-Related Marketing. Society for Marketing Advances (SMA). San Antonio, Texas.

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Fitzmaurice, J. (2005, November). Incorporating Consumers’ Motivations into the Theory of Reasoned Action. Wiley Periodicals, pp. 911-929.

- Foxall, G. R., Oliveira-Castro, J. M., & James, V. K. (2006). CONSUMER BEHAVIOR ANALYSIS AND SOCIAL MARKETING: Behavior and Social Issues, 101-125.

- Gill, P. S., & Raina, S. (2015). Cause Related Marketing and its Effect on Millennial. IOSR Journal of Business and Management, 60-67.

- Hanzaee, K. H., Sadeghian, M., & Jalalian, S. (2018). Which can affect more? Cause marketing or cause-related marketing. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 304-322.

- Hongwei, H., & Harris, L. (2020). The Impact of Covid-19 Pandemic on Corporate Social Responsibility and Marketing Philosophy. Journal of Business Research.

- Hossain, M. I., & Akter, N. (2020). Behaviour change during Covid-19: Could social marketing do it differently?

- Hyllegard, K. H., Yan, R.-N., Ogle, J. P., & Attmann, J. (2020). The influence of gender, social cause. Journal of Marketing Management, 100-123.

- Jane Coleman, L., Bahnan, N., Kelkar, M., & Curry, N. (2011). Walking The Walk: How The Theory. The Journal of Applied Business Research, 107-116.

- Jones, S. C., & Iverson, D. C. (2012). Pandemic influenza: a global challenge for social marketing. Faculty of Social Sciences - Papers.

- Keller, K. L. (1998). Branding Perspectives on Social Marketing. Advances in Consumer Research, 299-302.

- Kotler, P., Roberto, N., & Lee, N. (2002). Social marketing: Improving the quality of life. 2nd Edition. Sage Publications Inc.

- Kumar, A., & Dutt, V. (2020). CORONAVIRUS IMPACT ON MARKETING, ECOMMERCE & ADVERTISING: A DEEP STUDY. JOURNAL OF CRITICAL REVIEWS, 4469-4476.

- Lyong Ha, C. (1998). The theory of reasoned action applied to brand loyalty. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 51-61.

- Malviya, S. (2016, October 11). HUL’s share of hair care market just below 50%, say sources. Retrieved from The Economic Times: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/cons-products/fmcg/huls-share-of-hair-care-market-just-below-50-say-sources/articleshow/54786526.cms

- Massazza, A., & Joffe, H. (2020). Feelings, Thoughts, and Behaviors During Disaster. Qualitative Health Research.

- Mathur, S. P. (2020). Lasting Pandemic Impact on Marketing of Things. Mukt Shabd Journal, 6159-6164.

- Mukherji, U. P. (2017, June 20). ITC hopes to make Savlon a Rs 500 crore brand. Retrieved from The Times of India: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/india-business/itc-hopes-to-make-savlon-a-rs-500-crore-brand/articleshow/59235239.cms

- Natrajan, T., Arasu, S. B., & Inbaraj, D. (2016). A Journey of Cause Related Marketing from 1988 to 2016. International Journal of Business and Management.

- Oliveira, P. R. (2016). Customer Response to Message Framing in Cause Related Marketing. Goa, India: Department of Management Studies, Goa University.

- Online, B. (2020, May 24). Covid-19 Ads: How brands are taking the socially responsible route in their communication. Retrieved from Financial Express: https://www.financialexpress.com/brandwagon/covid-19-ads-how-brands-are-taking-the-socially-responsible-route-in-their-communication/1968768/

- Pandukuri, N., Azeem, A. B., & Reddy, N. T. (2017). Impact of Cause Related Marketing on Consumer Purchase Decisions on FMCG Brands in India. National Conference on Marketing and Sustainable Development, 74-85.

- PepsiCo leads in packaged snacks category; Lay's, Kurkure market shares shrink. (2019, May 07). Retrieved from Business Today: https://www.businesstoday.in/current/corporate/pepsico-leads-packaged-snacks-market/story/344027.html

- Punjani, K. K. (n.d.). INFLUENCE OF SOCIAL ADVERTISING ON CONSUMER BEHAVIOR TOWARDS FMCG BRANDS.

- Rajput, S., Tyagi, N., & Bhakar, S. (2013). SOCIAL CAUSE RELATED MARKETING AND ITS IMPACT ON CUSTOMER. Prestige International Journal of Management & IT- Sanchayan, 26-38.

- Sindhu, S. (2020). Cause-related marketing — an interpretive. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing.

- Singh, M. (2016). Awareness and Influence of Cause Related Marketing: A Study on Graduate and Post Graduate Students of Varanasi. Marketing Reborn: Traditions, Trends and Techniques. Ahmedabad: International Communication Management Conference.

- Singh, S. D. (2018). Cause-Related Marketing and Its Effect on the Purchase Behaviour of Indian Millenials. BHU Management Review, 1-11.

- Sourav. (2019, July 02). How Ghari challenged the Detergent Giants and emerged as a Market Leader. Retrieved from Next Big Brand: https://www.nextbigbrand.in/how-ghari-challenged-the-detergent-giants-and-emerged-as-a-market-leader/

- Vaaland, T. I., Heide, M., & Gronhaug, K. (2008). Corporate social responsibility: Investigating theory and research in the marketing context. European Journal of Marketing, 927-953.

- Vock, M., Dolen, W. v., & Kolk, A. (2013). Changing behaviour through business-nonprofit collaboration? European Journal of Marketing, 1476-1503.