Research Article: 2021 Vol: 25 Issue: 2

Strategising For Rural India: A Literature-Based Three Pronged Conceptual Model

Purnendu Kumar Patra, Research Scholar, Mahatma Gandhi Kashi Vidyapith

Dr. K K Agarwal, Mahatma Gandhi Kashi Vidyapith

Abstract

Strategy, as regards business, is a long term course of action to fulfill objectives. Organizations make long term plans to achieve their ends using means available to them internally and in the environment. All strategies tend to result in the firm achieving more than what a competitor achieves or lose less than what others do. Villages of India lack basic infrastructure, are agriculturally rich, are opposed to English language and practically to any fruitful activity contributing to economic growth. More than half of India lives in its villages which don’t even have access to basic life essentials like health, education, access and clean fuel. This set of challenges calls for a pragmatic approach in strategising for rural India. A review of literature was undertaken which revealed three, not very distinct, bodies of work covering the aspects of Marketing, Ethics and Innovation in strategy making. A conceptual plan was derived out of the study calling for an integration of all three aspects which has been posited to make Rural Marketing strategy a success. Gaps in research have been pointed out and recommendations made.

Keywords

Strategy, Rural, India, Marketing, Ethics, Innovation.

Introduction

Strategy, as regards business, is a long-term course of action to fulfill objectives of the firm. Even if an over-simplification of a more classical definition (Glueck & Jauch, 1988), it still fits the bill in the sense that organizations do make long term plans to achieve their ends using means available to them internally and in the environment. All strategies tend to result in the firm achieving more than what a competitor achieves or lose less than what others do. This is an outcome of distance of exogenous factors in the business environment from what would have been considered ideal.

The terms strategic marketing and marketing strategy have been used interchangeably, both being organisational constructs acting as one common conduit to fulfillment of objectives of the corporation (Varadarajan, 2010).

Strategy traditionally emanates from within the organisation, but is essentially a response to the broader external stimuli. This interface between the organisation and the environment necessitated a networked approached involving review of organisational scope or boundaries, factors controlling effectiveness of the organisation and the management of the strategy itself. In any context, the success of a network model of strategy will bank heavily on whether a company moves away from traditionally accepted styles of allocating resources and looks at innovating by taking into consideration all parties involved (Hakansson & Snehota, 2006).

Speaking of strategy at the international level, globalisation is considered the harbinger of equity, development and integration of geographically dispersed marketplaces into one mega, planet-sized market. However, since the Second World War, when the West decided to penetrate geographies not to plunder, but to trade, this “integration” has been a little off-mark. What could at best be called as semi-globalisation (Gehmawat, 2003). One might wonder if the author’s observations in 2003 and the reality in 2020 are any different. As a matter of fact, among the factors considered, viz knowledge, labour, capital and products, while the first two have still shown improvement as far as diffusion is concerned, what with the frenzied up-take of smartphones by millennials, the other two (more vital for marketing success) remain un-integrated, at least, as far as the multinationals are concerned. This results in a prolonged status quo as far as geographical disparity in income and economic development is concerned. Lack of fair trade, in letter and spirit has been a barrier to this diffusion of capital and products. The concept of fair trade aims to achieve sustainable development for the marginalised sections in developing countries using international trade as the focal means (Khanapuri & Khandelwal, 2011). With concentrated efforts from state, non-state and international players their model claims to achieve sustainability using means of international trade conditions, ensuring equitable development for the weaker producers and their workers.

The success of strategy thrives on market imperfections. Synergy that was unanticipated, luck favouring the seller and not the buyer, one firm having a cultural edge or low-cost production benefit nudging out another- such are the inadequacies of business (Barney, 1986). Sometimes they (imperfections) exist in abundance, while at others corporations need to look closer to find them in a seemingly inaccessible market. Rural India is just that: inaccessible. To a large proportion of corporations operating in India and abroad, country-side India has been like an exotic quarry ever so elusive to its predator, the weary marketer.

Although no sure recipe for success, (Bang et al., 2016) proposed a concept comprising three dimensions to determine the practical and theoretical utility of a model for realisation of marketing success, viz., marketing decisions, which help in assessing market potential and attractiveness of the product to the user and non-user segments; marketing activities necessary to target prospects, convert non-users into users and increase usage and competitive advantage, which is practically the end at which a marketer wishes to arrive through the former two.

Characteristics of Rural India

As Shah & Chattopadhyay (2014) note, villages of India lack basic infrastructure, are agriculturally rich, are opposed to English language and practically to any fruitful activity contributing to economic growth. More than half of India lives in its villages which don’t even have access to basic life essentials like health, education, access and clean fuel. Bio-mass burning is common practice in rural India. Not that there was no effort to change that. The Government of India did endeavour to give its rural folk ways to an improved lifestyle, or rather, a less risky one; the case here being that of the National Program on Improved Chulhas (Shrimali et al., 2011). However, efforts of the government went in vain, since many unseen product related hurdles like poor design, competition from existing low-cost stoves etc. remained unaddressed.

Among challenges faced by companies in rural India, prominent are (Prakash & Srivastava, 2009)

1. Proper communication of what comprises value

2. Educating villagers about need and usage of a product

3. Having a strategic intent instead of an opportunistic approach towards the rural market

4. Migration of suitable workforce from villages due to low job opportunities

5. Managing complex distribution channels

6. Creating trust in the minds of rural people

7. Shortage of infrastructure

Low literacy rates, traditional outlook, over-dependence of farmer purchases on monsoon and crop output, glaring infrastructure problems, communication issues, lack of economies in distribution have most often been quoted as challenges marketers face in rural India (Hagargi, 2011).

A considerable body of literature has proposed solutions to these problems in rural India. Local/district level empowerment of skill development units to prevent migration, creating databases for classes of labour, encouraging entrepreneurial content in training programs, introduction of vocal training in village schools and soft skills orientation (Patra, 2016).

Literature Review

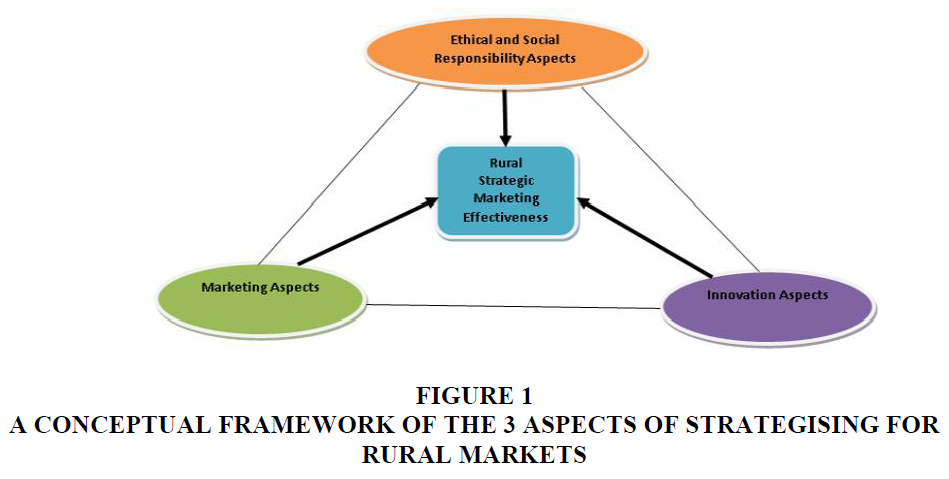

A study of contemporary and past literature, including seminal works by authorities in strategy, rural marketing and innovation was conducted. It was observed that there were three distinct bodies of academic work focused on strategy as concerns rural markets. Accordingly, they were studied under three sections, viz

1. Ethical and Social Responsibility Aspects of Strategising for Rural Markets (including role of the state)

2. Marketing Aspects of Strategising for Rural Markets

3. Innovation Aspects of Strategising for Rural and Bottom of Pyramid (BoP) Markets

Ethical and Social Responsibility Aspects of Strategising for Rural Markets

Rural markets significantly differ from urban markets thus requiring separate marketing strategies too. Promotional strategies must move from mass market to location specific or even client specific. In place of segregated inputs, the resources for distribution must be bundled at a location. Several unique demand patterns are observed in villages, each of which might not be applicable in the next rural destination. Hence management of demand and supply according to geographical uniqueness is of essence. Marketing must not and cannot be profit motivated. Villagers might feel cheated. Thus the developmental role of marketing must be brought to the fore. A USP that works for the urban buyer might backfire altogether in the Indian village. Positioning might have to be re-worked before entering the hinterland. Ethics play a huge role in marketing for rural India. If the rural consumers have the slightest whiff of foul play, they are likely to switch sellers or abandon the purchase (Kumar & Swamy, 2013).

From the governance perspective which has a significant impact on industrial development of a region, Industry Clusters of firms that are linked either horizontally through competition or vertically through the supply chain can be developed in rural areas, particularly the far flung areas like the North Eastern Region of India (Das & Ashim, 2011). Bamboo product clusters in Barpeta district of Assam have been cited as a successful implementation of this strategy. The benefits of clustering have been mentioned to be as under:

1. Pooling of labour is built-in into the industry clustering strategy because only the local small industries are targeted

2. Aids in ancillary eco-system development

3. Fosters building a value chain of suppliers, customers and investors which in result helps in developing several complementary businesses

4. Labour can demand and receive higher pay

5. Individual Small Scale units tend to specialise in specific tasks and skills.

6. Lower costs of inputs, labour and information

7. The cluster behaves like a market, in the way that it enables dissemination of product, skill and technical know-how from unit to unit.

8. From local to global, the clusters are the fastest way to export enrichment.

Corporations and their role as community development partners has recently been a matter of intense scrutiny. Although traditionally the onus of social development has been on the state, the popularity of market economies has led to a new order in nations, that of Corporate Citizenship (Moon, 2007; Margolis & Walsh, 2003; Idemudia, 2008; Hamann, 2006). In recent years firms are being increasingly viewed as catalysts of social change through business and nonbusiness activities. Organisations, on their part are manifesting their social responsibilities by resorting to innovation andinclusion (Idemudia, 2008; Moon, 2007; Eweje, 2006; Griesse, 2007; Hamann, Introducing corporate citizenship, 2008; Hopkins, 2007) in all their strategic initiatives, particularly for rural folk. Closer home in India, Anurag Gupta (Arora & Kazmi, 2012), founder of A Little World(ALW) with the help of an innovative Business Correspondent(BC)interface called Zero Mass Foundation(ZMF) was instrumental in gaining financial transactions from over 4 million rural customers who had little or no to technology for money transfer. All they had was a simple savings account in a bank. This led the leading state-run incumbent SBI (State Bank of India) to acquire a 20% stake in Gupta’s ALW.

As a case of incoherence of organisational commitment to strategy, HP’s failed project “i-communities” had started off with much fanfare and goodwill. It aimed at achieving development in rural Andhra Pradesh through its aforementioned program. But due to lack of clarity over a probable exit, missing sense of accountability and lack of ownership from local organizations meant that the technology giant had to walk out unsatisfied (Schwittay, 2008).

From a state point of view, particularly with respect to marketing of agricultural output which is the bread winner to a majority of households of not just rural India, but the nation as a whole the following observations have been made:

Conflicting goals of consumers (who want cheap food) and farmers (who want higher prices), must be efficiently met. The producer must have accessibility and ease to the market for selling his produce; he must have sufficient information flow about the market. On the other hand the customer must get value of his purchase. Producer must be free to choose the market to sell the products according to his/ her convenience. There should be more liberal policies in food grain management, international trade with domestic market reforms, allowing greater role of private players in an open-economy environment. (Patra et al., 2017)

Marketing Aspects of Strategising for Rural India

As an instance from international markets, a study conducted in two locations (CocaStefaniak et al., 2010), one in Spain(Seville) and one in UK(Perth) found that at one location(Spain) retailers had a more restricted view(up to a street or neighborhood level) of what is called “localization” while in UK, respondents thought of the entire town or village as “local”. This is pertinent to the ‘Place’ factor in marketing. Similarly, it was found at both places that retailers had a common view to customers, in that they felt the buyers wanted more education than just product knowledge, preferred customer service, and valued customer retention. This refers to the ‘People’ aspect of marketing. Further, positive word-of-mouth by satisfied customers and their perceptions of the store were viewed as Critical Success Factors to survival as well as differentiation by retailers. This is in connection with the Promotion aspect of marketing. Thus, localisation as a marketing strategy has held the retailers of these locations in good stead despite severe competition from new formats.

Back home in India, Neelam (2017) proposed several changes to traditional marketing strategies adopted by companies to be effective in villages. Local language(dialect) as preferred medium of communication, orientation-shift to view rural folk as premium buyers along-side being value-purchasers, creating a product perception matching the product utility and not deceptive marketing, highly differentiated products for rural markets, etc featured in recommendations. Interestingly, company objectives and overall attractiveness were also part of strategic change required according to the research (Neelam, 2017).

Ahmed (2013) researched the perception of rural customers regarding life insurance policies. He observed that from marketers’ point of view, it is more important to judge the perception of rural customer regarding the said service and not what they knew. The awareness of life insurance per se was found to be low. Consequently, the need-satisfaction-delighthappiness continuum was uninitiated. There was a need for marketers to admit this ‘moment of truth’ in order to further propel a mission to create awareness among the rural populace. Some novel tactics were proposed such as promotion through publicity vans, curiosity-arousing visuals, alongside strategies to educate rural masses as regards the need to protect livelihood, belongings, crop; engaging reputable NGOs, using field forces with excellent local communication abilities and so on. As a finding, it was observed that micro finance companies were using mobile communication to increase their reach India’s villages. Some important suggestions proposed included reducing product complexity, crafting an appealing positioning and utilizing last-mile distribution networks

Nokia 1100, Godrej Chotu Kool refrigerator can be cited as examples of product designs for rural markets. Tactics like refill packs (Bru, Horlicks, Boost), striking colours in packaging like Red Label tea, Nyle Herbal Shampoo, Colgate’s red and white packet were strategies endemic to rural populace. It must be further noted that decreasing product complexities by bundling together multiple benefits in a simple product (Tata Swach) works well for villagers. An interesting observation in branding strategy is that naming of a certain product must be carefully planned if it is to be positioned with the Indian villager in mind. Names need to be such that they relate to the rural way of life. Be it the name of a popular Goddess (Tata Shaktee), the aspiration of rural parents as concerns their wards (Britannia Tiger) or respect towards position power (Mahindra’s Bhoomiputra tractors), each brand that tasted success in rural India has without fail borne an integral element of the village life in its name. Another observation has been regarding general sturdiness of a product. This product feature has been cited by many researchers. Villagers in India prefer a strong-looking and robust-feeling product to one that might be strong, but appears flimsy. Eveready’s metallic torches are cited to have a lion’s share in the Indian rural market because of its sturdy looks and surprisingly good scrap value. Pricing needs to be such that the low denominations commanded a high volume. Rs. 5, Rs. 1, Rs. 10 packs of shampoos, oil, detergent etc were found to be far more popular than their bigger-sized packets which found more takers in cities. Self Help Groups (SHGs) may be recommended as a suitable channel for distribution of FMCG products. Haats or periodic markets were a powerful means to gain a footing in the interior markets. These gatherings could account for the population in a diameter of about 10-15 kilometers, taking into consideration the fact that in India villages with population less than 5000 are scattered over small distances, thereby making it economically unviable for corporate brands to centralize their presence at a certain town (Betala, 2017).

A significant industry in rural India is that of dairy. India is among the leading milk producers of the world. Unorganised farmers are in a majority Kale et al. (2018) while the organized dairy sector is also catching up fast. The former is more of a supplement to a main source of income (Sharma et al., 2002) while the latter is set up with an intent to commercialise and expand. Globally, the dairy sector has undergone sea changes owing to modernization and technological up-gradation (McMahon et al., 2017). In the Indian market, average per capita consumption of milk has been observed to be higher than the global benchmark (Ohlan, 2016). However, the industry is not free of challenges with the following leading the list (Kamath et al., 2019):

1. Increasing fuel prices leading to high production and transportation costs

2. Lack of information when starting up

3. Low veterinary consultants to cow ratio

To overcome the cost overheads arising from the above issues, the authors use Participatory Systems Mapping (PSM) to simulate future yield of sample dairy farms and conclude that the sole strategy to tide over such crises as mentioned above was to re-brand the milk as organic and sell at a premium. Re-positioning is as such recommended across product categories if brands intend to penetrate hinterland India. Much as it appears only obvious, many marketers have made the strategic mistake of releasing brands as it is, in a one-size-fits-all, in Indian villages. Not surprisingly, they have had to pull out of these geographies following abysmally low sales volumes and mind shares.

The prospect of rural enterprises is bright in India given a proper e-business strategy (Misra, 2008). Farmers associated with dairy cooperative Amul tend to manage their interests very effectively through collective bargaining with the major challenge being the interface between the proprietary DISKs (Dairy Information System Kiosk) and the back-end ERP(Enterprise Resource Planning)system. Whereas interfaces for customers are quite welldefined, the supplier interface in the back-end needs support from the national ICT network (Information & Communication Technology). This is an example of digitalization strategy at work, where the information architecture enables business processes such that the weakest and least capable human element in the system does not face technical hurdles. This is all the more surprising considering the fact that rural customers are proven technology illiterates.

Innovation Aspects of Strategising for Rural and Bottom of Pyramid (BoP) Markets

Some most often cited examples of Indian rural innovation include HLL’s Annapurna Salt, HUL’s Project Shakti, Amul, Project Dharti of Godrej, DCM Shriram’s Hariyali Kisan Bazaar, Triveni Kushal Baaar, Godrej Chotu Kool (Hagargi, 2011). But the concept of innovation as visualized from India’s rural consumer point of view has four dimensions, namely: awareness, access, affordability and availability (Prahalad, 2012). There will always be constraints on the way to an innovation, perhaps these being necessary for the process after all. Issues extraneous to the innovators environment must be transformed into opportunities. This is particularly relevant in case of India’s villages. Be it regulatory hurdles, social mindset, a dearth of ecological resources or challenges arising out of the terrain, there could be no one solution to India’s kaleidoscopic diversity and the problems arising out of it. All examples cited above point towards the use of Prahalad’s Innovation Sandbox (Prahalad, 2006)

What necessitates companies to innovate on the strategy front? After all, strategy is one big plan, just like any other. In the rural populace, companies are faced with insurmountable challenges which pose many more questions that need answering if they need to survive. If there is no TV or radio in a region, how do marketers get their messages across (awareness)? If a majority of the 640, 000 thousand villages of India are far flung, how do they push their physical stock beyond the last mile (access)? If they somehow manage to get the stock across the terrain, would it be economically viable each time an order is fulfilled (available)? If economy is compromised how do they keep the price in check (affordable)? Hence there is a need to innovate on each of the marketing and product design aspects. Thus, there is also the need to reinvent strategy.

Bottom of the Pyramid, as explained by Prahlad, refers to the 4 billion-odd people living in the lower-most section of the economic pyramid throughout the world. These customers, hitherto not considered marketable, are characterised by extreme price sensitivity, very low purchasing power and the most significant of all, rock bottom levels of aspiration. These paramters are essential for marketers to create demand in spaces where products can’t be sold directly on the basis of pull from the market (Patra, 2019).

To succeed in BoP markets, evidence from literature strongly recommends innovation, one which costs very little. Low cost innovation is characterised by elimination of non-essential product features, focus on products that are just ‘good enough’, remodel-ready offerings, multiple applications of the same technology, being more environmentally friendly and related development having their starting points at the price (Agnihotri, 2015).

Esposito et al. (2012) note some key principles for sustainable healthcare service provisioning particularly tailored for the BoP markets. A critical need to super-segment the heterogeneous subsistence markets, focus on the 4As of Prahlad (Prahalad, 2012), not to assume anything about the markets, engage with the markets, to build local capacity, experimentation as a key to differentiation, regulatory alignment and not just compliance, stressing on scale and building collaborative platforms were cited as important

Discussion

A conceptual framework is represented in figure 1 above representing the gist of what can be called an analysis of existing research on the strategic marketing aimed at capturing, penetrating, dominating and sustaining rural marketplaces.

As much as marketing is critical for success in the said market segment, ethics cannot be compromised. It is of equal importance that the state plays a pivotal role in economic growth of subsistence markets using firms as catalysts and partners in development.

Scope for Future Research

While this work may be a good starting point to get a bird’s eye view of existing literature on the subject, an empirical investigation would be more fruitful in giving valuable insights into consumer aspects, marketer aspects and governance aspects of the situation. Hence it can serve well as a ready reference for an empirical research.

Some gaps have also been spotted in the literature. It was found that more qualitative research (ethnographic studies, in-depth interviews, Delphi techniques, etc) tools were utilised by researchers to arrive at facts as opposed to the common notion of empirical research. This could point to a revelation that the rural customer is indeed a complex candidate for quantitative insights. Moreover, there was a lack of evidence regarding information search functions of rural consumers. Mostly push marketing has been used by marketers to feed their offerings to villagers, but it is a known fact that rural or urban, consumers are curious by nature. This aspect has been left unattended by not just companies but academicians too. Hence future academic focus on this particular function of rural consumer behavior can be taken up to yield better understanding of villages and thus, more customized communications strategies can be recommended.

Conclusion

A close look at contemporary academic works on strategic marketing reveals that uniqueness, customisation, localisation, repositioning, digitalisation and innovation are critical to succeed in rural and subsistence marketplaces. Both services as well as products must be designed keeping the rural consumer in mind. Technology has the capacity to be a great provider for firms if they it is custom built and deployed for the weakest customer in the village. Innovation at the village level may come from anywhere, be it a small change in package design or a major overhaul of communications strategy. But all firms wishing to target two thirds of India’s population must innovate. Differentiation must be based on unique attributes of the product and not just promotional discounts. As a matter of fact, rural India has matured more than expected and is no more available to price cuts and clearance sales. Hence, if marketers realise that they must plant a foot in the countryside for the long haul, the rural folk will trust they are here to stay. Above all, ethics is a matter of great importance, since the village population places as much trust on the seller as was the genuineness in their last interaction

References

- Agnihotri, A. (2015). Low-cost Innovation in Emerging Markets. Journal of Strategic Management , 23(5), 399- 411.

- Ahmed, A. (2013). Percpetion of Life Insurance Policies in Rural India. Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review , 2(6), 17-24.

- Arora, B., & Kazmi, S.B. (2012). Performing Citizenship:An Innovative Model of Financial Services for Rural Poor in India. Business & Society , 51(3), 450-477.

- Bang, V.V., Joshi, S.L., & Singh, M.C. (2016). Marketing strategy in emerging markets: a conceptual framework. Journal of Strategic Marketing , 24(2), 104-117.

- Barney, J.B. (1986). Strategic Factor Markets: Expectations, Luck, and Business Strategy. Management Science , 32(10), 1231-1241.

- Betala, A.S. (2017). Rural India- The Golden Bird: Exploring the Real Bharat. BIMS International Research Journal of Management and Commerce , 2(4), 1-14.

- Coca-Stefaniak, J.A., Parker, C., & Rees, P.L. (2010). Localisation As a Marketing Strategy for Small Retailers. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management , 38(9), 677-697.

- Das, R., & Ashim, D.K. (2011). Industrial Cluster: An Approach for Rural Development in North East India. International Journal of Trade, Economics and Finance , 2(2), 161-165.

- Esposito, M., Kapoor, A., & Goyal, S. (2012). Enabling healthcare services for the rural and semi-urban segments in India: when shared value meets the bottom of the pyramid. Corporate Governance International Journal of Business in Society , 12(4), 514-533.

- Eweje, G. (2006). The role of MNEs in community development initiatives in developing countries: Corporate social responsibility at work in Nigeria and South Africa. Business & Society , 45(2), 93-129.

- Gehmawat, P. (2003). Semi-globalization and International Business Strategy. Journal of International Business Studies , 34(2), 138-152. Glueck, W.F., & Jauch, ,. L. (1988). Business Policy and Strategic Management (5 ed.).

- McGraw-Hill. Griesse, M.A. (2007). The geographic, political, and economic context for corporate social responsibility in Brazil. Journal of Business Ethics , 73(1), 21-37.

- Hagargi, A.K. (2011). Rural Market in India: Some Opportunities and Challenges. International Journal of Exclusive Management Research , 1(1), 1-15.

- Hakansson, H., & Snehota, I. (2006). No business is an island: The network concept of business strategy. Scandivanian Journal of Management , 22, 256-270.

- Hamann, R. (2006). Can businesses make decisive contributions to development? Towards a Research Agenda on Corporate Citizenship and Beyond. Development Southern Africa , 23(2), 175-195.

- Hamann, R. (2008). Introducing corporate citizenship. In S.W.R. Hamann, The business of sustainable development in Africa: Human rights, partnerships, alternative business models (pp. 1-35). Pretoria, South Africa: UNISA Press.

- Hopkins, M. (2007). Corporate social responsibility and international development:. London: Earthscan. Idemudia, U. (2008). Conceptualizing the CSR and Development Debate: Bridging Existing Analytical Gaps. Journal of Corporate Citizenship , 29, 91-110.

- Kale, R.B., Ponnusamy, K., Chakravarthy, A.K., Sendhil, R., & Mohammad, A. (2018). Future aspirations and Planning of Dairy Farmers in India: Horizon 2020. Indian Journal of Animal Sciences , 88(4), 493-498.

- Kamath, V., Biju, S., & Kamath, G.B. (2019). A Participatory Systems Mapping (PSM) based approach towards analysis of business sustainability of rural Indian milk dairies. Cogent Economics & Finance , 7(1), 1-16.

- Khanapuri, V.B., & Khandelwal, M.R. (2011). Scope for fair trade and social entrepreneurship in India. Business Strategy Series , 12(4), 209-215.

- Kumar, K.P., & Swamy, S. (2013). Indian Rural Market: Opportunities and Challenges. Trans Asian Journal of Marketing and Management Research , 2(2), 40-47.

- Margolis, J.D., & Walsh, J.P. (2003). Misery Loves Companies: Rethinking Social Initiatives by business. Administrative Science Quarterly , 48, 268-305.

- McMahon, M., Pieters, L., Schnuck, P., & Kroef, R. (2017). Global Dairy Sector- Trends and Opportunities. Delloitte Consulting, Netherlands. Netherlands: Delloitte. Misra, H. (2008). Prospects and Challenges in Implementing E-Business Strategies for Rural Enterprises: A Case of Dairy Cooperative in India. Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE ICMIT (pp. 486-491).IEEE.

- Moon, J. (2007). The Contribution of Corporate Social Responsibility to Sustainable Development. Sustainable Development , 15(5), 296-306.

- Neelam. (2017). Rural Marketing-Challenges, Opportunities and Strategies. International Journal of Academic Research and Development , 2(5), 384-388.

- Ohlan, R. (2016). Dairy Economy of India: Structural Changes in Consumption and Production. South Asia Research , 36(2), 241-260. Patra, P.K. (2019). A Review of Contemporary Global Literature about studies on Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid. In P.P.PN Jha, Spirituality Beyond Repertoire: Leadership and Happiness Perspectives (pp. 113- 120). New Delhi: Excel India.

- Patra, P.K. (2016). Rural Development and Employment through Skill Development . SMS Journal of Entrepreneurship & Innovation , 3(1), 34-42.

- Patra, P.K., Kumar, S., & Pratap, V. (2017). Agricultural Marketing in India: Challenges and Prospects. In S. D. Raj Kumar, Agri Business Marketing (pp. 44-53). New Delhi: Bharti Publication.

- Prahalad, C.K. (2012). Bottom of the Pyramid as a Source of Breakthrough Innovations. The Journal of Product Innovation Management , 29(1), 6-12. Prahalad, C.K. (2006). The Innovation Sandbox. Strategy+ Business , 44, 1-10.

- Prakash, J., & Srivastava, A. (2009). Management of Rural Marketing: Oppportunities and Challenges ahead. Saaransh RKG Journal of Management , 1(1), 1-6. Schwittay, A. (2008). 'A Living Lab': Corporate delivery of ICT in Rural India. Sceince, Technology and Society , 13(2), 175-209.

- Shah, M., & Chattopadhyay, N. (2014). Innovation in Procurement from Rural India using Enterprise Mobility Strategy: A Case Study. World Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development , 10(2), 143-153.

- Sharma, V.P., Singh, R.V., Staal, S., & Delgado, C.L. (2002). http://www.fao.org/WAIRDOCS/LEAD/X6115E/x6115e0b.htm. Retrieved from www.fao.org.

- Shrimali, G., Slaski, X., Thurber, C.M., & Zerriffi, H. (2011). Improved stoves in India:A study of sustainable business models. Energy Policy , 39, 7543-7556.

- Varadarajan, R. (2010). Strategic marketing and marketing strategy: domain, definition, fundamental issues and foundational premises. Journal of The Academy of Marketing Sciences , 38, 119-140