Research Article: 2022 Vol: 26 Issue: 5

The Effect of Politicians use of Social Media on Citizen Political Commitment

Senda Baghdadi, University of Carthage

Fatima Toukebri, University of Carthage

Citation Information: Baghdadi, S., & Toukebri, F. (2022). The effect of politicians’ use of social media on citizen’ political commitment. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 26(5), 1-16.

Abstract

Nowadays social networks play a crucial role in political communication. Whether it is contact networks (FB, Linkedin) or content networks (Instagram, you tube etc.), politicians are aware of the importance of these tools to communicate and interact with citizens. Then, first, the authors rely on theory to present the concept of citizens’online and offline political commitment. Second, they present the theoretical framework that identifies the importance of social mediause by politicians, particularly Facebook, on the outcome of presidential elections. Third, the authors explore the practices of using this media, and its effects on citizen commitment in order to draw out implications on an election campaign.

Keywords

Political Marketing, Political Commitment, Social Networks, Social Media.

Introduction

There are now 4.66 billion Internet users worldwide, or 4.2 billion uses of social networks (Hootsuit 2021). Technological developments are creating a rapid flow of information, a simulation of political debates, interactivity between political parties and the public, and effective mobilization of the electorate (Gibson et al. 2003; Vedel 2003). Political institutions and actors use social networks to foster citizen commitment and proactively manage flow of information (Goveran 2013). Consequently, social media has become the medium for all political communication (Safiullah et al. 2017). The question that arises is what effect does the use of social media, by politicians, have on citizen commitmentduring an election period?

Then, this study makes five main contributions. First, we introduce the concept of commitment in marketing in general and in political marketing in particular by defining the concept and presenting the different forms of online and offline commitment in the same study. Second, we build a theoretical typology of all the use dimensions of social media and Facebook, by politicians, in the same study. Third, referring to theory we examine how the use of FB affects the political commitment of citizens, online in the first place and offline in the second (voting results). Fourth, the authors will offer politicians some recommendations for use in their election campaigns. One objective for this study is to examine the implication of all factors on voting results Gerodimos, R., & Justinussen (2015).

Review of Literature

Offline Political Commitment

After reviewing the literature, the authors found that the concept of commitment is discussed in sociology, political science, educational psychology, organizational behavior, and lately in Marketing (Barger et al. 2016; Chahal & Rani 2017; Triantafillidou and Siomkos 2018; Kosiba et al. 2018a; Hollebeek et al. 2018).

Commitment in Marketing

Commitment has been studied in the literature (Hollebeek et al. 2011; 2014; Dessart et al. 2015; Leckie et al. 2016; Kunz et al. 2017) and denotes the relationship between individual and their actions (Kiesler 1971). In Marketing, this concept has been widely studied (Brodie et al.2013; Pansari & Kumar 2017).It is defined as "Who engages in What" (Angeles Oviedo-Garcia et al, 2014). It reflects psychological, motivational, and behavioral dimensions (Bowden 2009, Brodie et al. 2013). Other researchers have defined consumer commitment bycognitive, emotional, and behavioral dimensions (Doorn et al. 2010 in Hollebeek and Chen 2014; Hinson, Boateng and Renner 2018). The cognitive dimension refers to an individual's level of involvement with a brand, which is explained by the interaction with the brand (Molle & Wilson 2010). The emotional dimension refers to the satisfaction, and joy of the consumer during the interaction with the brand (Schaufeli et al. 2002; Leckie et al. 2016). Finally, the behavioral dimension refers to action, it is the fact of devoting time and effort to a brand-related action (Patterson et al. 2006; Leckie et al. 2016).

Commitment in Political Marketing

In political marketing, the concept of commitment refers to "a move to action". In the literature, this concept takes several forms. Leston-Bandeira (2013) First, political commitment essentially consists in engaging in a political activity, from the least intense activities, such as registering on electoral lists (Perrineau et al. 1994). Such commitment takes the form of voting, which is the most cited form and is considered the clearest way for citizens to express their opinions and choice in elections. Voting is also considered a preferred means of expression (Anne 2010). Unlike popular belief, abstention or the blank vote is also considered to be a form of commitment, since the citizen expresses his or her dismay when faced with a set of candidates that do not suit him or her. The second form of commitment is associative commitment, which is the attitude of supporting or actively participating in the defense of a cause or an idiology of a political party, or joining a union or an association (Duclos & Nicourd 2005). This is known by a more intense activity, such as taking a stand (Perrineau et al. 1994). Political commitment also refers to citizens’participation in political life by exerting influence on those in power. Finally, the third form of political commitment is called "committed consumption". It is "a consumption actor". More specifically, through their consumption the citizen defends causes or fights against ideas. It is a means of identity expression that allows to assert political positions. To engage in such a course, it means that citizens want to change a situation which is not appropriate anymore and to defend the interests of the people to whom they belong. In this study, we are interested in the first form of commitment, "voting".

Online Political Commitment

"Electronic discussion has a direct influence on the subsequent commitment of Internet users" (Smith 2006). Commitment on social networks/media has been the subject of several studies. This type of commitments known as "online commitment". It has been defined as "the motivation to interact and cooperate with community members" (Algesheimer et al. 2005).

Definition of Media/Social Network

Several definitions of media have been proposed in the literature (Su et al. 2015).The most recognized by researchers is the one that defines media as "the means of interaction between people in which they, create, share, exchange and comment on content with each other in virtual communities and networks" (Ahlqvist et al. 2010). Diffusion of content can take the form of photos, videos, ideas, opinions, interests and news (Drury 2008). In addition, the media used to diffuse this content, include, blogs, vlogs, podcasts (e.g. Flickr), forums, social bookmarks (e.g. Del.icio.us), social networks (e.g. Facebook, Twitter) and wikis (e.g. Wikipedia) (Drury 2008).The interactivity of social networks allows for information to be presented through multiple modes; text, audio and videos, and which can potentially attract voters and increase their political commitment (Xu & Sundar 2014). Function-wise, social networks can be dividedinto two categories, either contact social networks or content social networks (Ellison et al. 2007). Contact social networks allow users to expand their contacts in different networks such as their social network (e.g., Facebook) or their professional network (e.g., Linkedln). Content social networks offer the ability to share all types of content such as photos (e.g., Instagram), videos (e.g., YouTube), links (e.g., Delicious) etc. (Mangold and Faulds, 2009). A social network can be both a content and contact network like Facebook. Previous studies of the use of marketing on social networks are divided into two perspectives: an audience perspective and a business perspective (Tafesse, 2015). Our study focuses on the audience perspective.

Measurement

The main tokenused to measure the interactivity of a social media page is the number of "likes," "shares," and "comments" (Kietzmann et al. 2011; Bene 2017). The number of "likes" and "shares" are used as a sign of popularity for politicians using Facebook during elections and reflect their ability to mobilize and recruit potential voters (Williams and Gulati, 2007; Keat 2012). For this reason, candidates often publicly brag about the number of Facebook "likes" and "shares" of their posts and frequently encourage their Facebook members to share or like their posts in order to boost these numbers (Bender 2012). Several studies have shown that announcing the number of followers not only grants a certain status to the candidate but also a key element in creating a political fan base "fandom politics" (Williams and Gulati 2007; Keat 2012; Bronstein 2013).

The Effect of Politician’use of Social Networks on Political Commitment of Citizens

Citizens can be political or apolitical, and can express four profiles namely, activists, supporters, networks and other voters (Russmann 2011).

Effect by Level of Commitment

Effect of social networks use on politically committed citizens "The political"

The authors found that the use of social media promotes citizen commitment and further strengthens political commitment. The use of these new technologies in election campaigns has become an emerging need (Justinussen 2015). However, because of the ease and simplicity of these networks, the political, called party activists, can share the information they find online to less interested people. In addition, more informed citizens will tend to be more interested in politics and more actively engaged in the democratic process. (Giasson et al. 2013). The more individuals express themselves politically through social networks, the more they also try to mobilize other citizens (Rojas and Puig-i-Abril 2009).

Effect of social networks use on politically uncommitted citizens "The a-political”

In the literature, we found that the apolitical nature of social media can attract individuals who do not intend to engage with political institutions (Wojcieszak and Mutz 2009). Through these means of communication, political parties are able to communicate with a large number of citizens by exposing them to a range of political information that they may not have been seeking. Furthermore, participation in political discussions on social networks can expose individuals to relevant political information, which can motivate them to actively participate in politics and take further action (Vaccari et al. 2015).The act of obtaining information online and sharing that information is the first step and the foundation of political commitment (Berger 2009; Vaccari 2013). Research also shows that digital media can lead to a restructuring of political participation.It is a new participatory form that is more active and pushes citizens to be more involved and therefore promotes political commitment(Gibson & Cantijoch 2013). This commitment is based primarily on spontaneous values, which come in an unplanned manner and occur in informal interactions, i.e. in citizens' daily lives rather than in party-controlled environments (Chadwick 2009; Vaccari et al.2015).

Elements Affecting Online Political commitment

According to the literature, there are four mainfactors that influence citizens' commitment (1) the online presence of political candidates (2) the typology of accounts on social networks (3) the number of subscribers (4) the content published on social networks Becker (2012).

The online presence of candidates

Facebook offers an opportunity for candidates to communicate, interact and encourage political commitment among citizens. Barack Obama's campaign is an example. In 2012, he launched an app on Facebook allowing supporters to connect with the campaign and share content online. Over half a million supporters followed the Facebook campaigns and asked their friends on FB to register to vote (Scherer 2012). Using FB has a quick and effective effect on its users. It can be used to foster citizen support and commitment (chen 2017).

Typology of FB accounts used by politicians

Political candidates may differ in the way they manage their social media presence and may also choose the type of Facebook account to foster relationships with their supporters. A political candidate's choice of Facebook account type is likely to signal how they perceive themselves and position themselves to their voters (Thomson 2006). Facebook allows candidates to create a "page," "profile" or "group," which in turn allows fans to "like" a page, "follow" a profile, or "join" a group (Lin 2017).

A "Page" is designed to be the official account of entities such as brands or political candidates, who may have an unlimited number of fans and the ability to verify the account (Lin, 2017). It could be perceived by voters as more professional, as it could be presented as a human brand that allows candidates to focus on political issues and public image (Thomson 2006).

A "Profile" is designed as a personal account (Baum & Groeling 2008) where users can have both friends and followers (Lin 2017). Candidates can use their personal "profile" account to support their election campaign in social media, and can also post personal messages with their political views (Lin 2017).

A "group" is conceived as an "online collective" where people can share their interests and express opinions. It could be seen as a less formal community where users can collectively discuss certain political issues. Moreover, groups may also have more ambiguous origins and administrators, making them seem like a less official and trusted source (Lin 2017).

Number of subscribers "Fans"

Lin (2017) found a relationship between the number of fans of candidates and their election results. Candidates can post videos, photos, events, messages, status and questions on their accounts. This content can relate to their political positions, their personal lives, greetings sent to their supporters or attacks on their opponents. Fans can choose to like the posts to show their support, comment on the posts to interact with the candidates or other subscribers, as well as share them with their friends. Research has shown that candidates should actively increase the number of fans and selectively choose which posts to publish (Zhang & Peng 2015). Each post by a candidate can increase their visibility on fans' news feeds, but it could also increase the chances that fans will disengage as a result of receiving a large number of candidates' posts. Candidate posts are likely to have positive, neutral, or even negative implications.

Message Content

Political messages, via social networks, can be analyzed in three dimensions (1) Aristotelian persuasive language (2) message vividness (3) raised topics.

(1) Aristotelian persuasive language consists of three themes (Bronstein 2009). First, messages classified under the Ethos theme create a personal image of politicians by writing about their political activities and achievements, personal life and family. Second, Pathos is an emotional or motivational appeal intended to convince an audience by creating a bond between the politician and the audience appealing to their emotions. Third, Logos is an appeal to logic intended to convince an audience by using reason, presenting numbers, statistics etc.

(2) message vividness. Vividness reflects the richness of an information and the extent to which a brand publication stimulates the different senses (Steuer 1992). It can be achieved by including dynamic (contrasting) animations, colors, images (Cho et al. 2002) or videos (Romano et al., 2005). Vividness in communication is eye-catching, it makes the content more likely to be seen, and in turn to be liked and shared (Cvijikj & Michahelles 2013); Using more vivid content could gain a greater reach as users seem eager to share content that will appeal to their network. According to the literature, videos and images receive the most likes and shares. Videos are the most likely to be viewed on Facebook (Bene 2017; Bossetta 2018).

(3) raised topics: Several previous studies have examined the topics or themes discussed on the social media pages of political parties and politicians (Aharony 2012; Adams & McCorkindale 2013; Bronstein 2013; Ceccobelli & Cotta 2016; Justinussen 2015; Larsson 2017a). The topic categories are presented as follows:

-Economics: economic indicators and/or data or the candidate's proposals on economic issues.

-Education: educational issues and/or the candidate's proposals on the topic.

-Elections: political propaganda describing politicians' proposals and/or negative propaganda against their opponents.

-The Party: various topics covering the mission, policy and activities of the party.

-The Politician: issues related to the politician, including activities and personal life.

-Security: issues related the security of the country.

-Society: different social issues such as illegal immigration, poverty, smuggling, social inequality and unemployment.

-Rallycalls: calling on citizens to participate in meetings or rallies.

Methodology

This study examines the sample period covering the last presidential elections in Tunisia in 2019. Tunisia is a North African country located on the Mediterranean coast and bordering the Sahara. It has 11000 inhabitants in 2019 and 12130 in 2022.

The elections were held in an early manner, on September 15, 2019 in Tunisia and from September 13 to 15 abroad for the first round, and October 13, 2019 for the second. It aims to elect the president of the Tunisian Republic for a term of five years. Initially scheduled for November 17, 2019, the election is advanced due to the death of the sitting president, Beji Caid Essebsi, on July 25, 2019. The election campaign for the 1st round was from 2 to 13 September in Tunisia and from August 31 to September 11 abroad. The campaign of the 2nd round was from September 26 to October 11 Harris & Harrigan (2015).

The number of registered Koc-Michalska (2017) voters, in the first round was 7074566, and the number of voters 3465184 or 48.98%. In the second round was 3892085 voters.

We recall the main question this study is trying to answer: what is the effect of politicians’ use of Facebook on citizens’ commitment during an election campaign? Our main question is reformulated in sub-questions as follows:

Research Questions

1. What is the effect of the presence of election candidates on Facebook on the political commitment of citizens?

2. What type of Facebook account should a candidate use to ensure citizen political commitment?

3. Does the number of fans of a political candidate has an effect on citizen political commitment?

4. How does shared content affect citizen political commitment?

5. What language of Aristotelian persuasion is used to ensure citizen political commitment?

6. What type of message vividness has an effect on political commitment?

7. What issue(s) should a presidential candidate choose to ensure citizen political commitment?

To answer these questions, we opted for the qualitative method, netnography, also known as online ethnography. This method allows for analyzing Yarchi (2018) consumer behavior through the study of virtual communities. (Kozinets 1998, 2002).

One of the advantages of netnography is its "unobtrusive" nature. Everything can be observed and recorded in a natural environment created by the subject and not artificially constructed by the researcher (Kozinets 2002). It is very useful because it allows to obtain measurable and comprehensive results, despite its qualitative nature. According to Bertandias & Carricano (2006), there are many possibilities for processing data, from simple content analysis to forms of statistical analysis. This feature makes netnography as the most appropriate qualitative research method to determine the main effects of political candidates’use of social media on citizen commitmentin the last presidential election campaigns in Tunisia.

Forthe data collection method, we followed Kozinets (2002) and eliminated the validation phase as proposed by Bryman (2012), namely entry, collection, analysis and interpretation.

Joining Virtual Communities

Twenty-six candidates presented theircandidacy for the presidential office.The authors selected five candidates based on a convenience method, the five who toppedthe 1st round results, presented in Table 1 below:

| Table 1 Candidates who Used Facebook and Retained for this Study | ||||||

| Name | Age | Party/ | Affiliation | Education | 1st round | 2nd round |

| Independent | ||||||

| Kaeis Saeid | 62 years | independent | - | Academic-Constitutional Law | 18.40% | 72.71% |

| Nabil Karoui | 56 years | « In the Heart of Tunisia»Party | Center | Business man/advertising industry | 15.58% | 27.29% |

| Abdelfatah Mourou | 71 years | EnahdhaParty | Far right | Lawyer | 12.88% | |

| Youcef Chahed | 43 years | «Live Tunisia»Party | Center | Agricultural Engineer | 7.38% | |

| Lotfi Mraihi | 59 years | «The republican popular union»Party | Center | Pulmonologist and writer | 6.56% | |

Data Collection from Virtual Communities

Research field: Facebook was chosen as the main network for our study, as it is the most used social networking site in Tunisia. In January 2019, the year of the last elections, there were 7,300,000 Facebook accounts in Tunisia (source Facebook ADS) Kruikemeier Sanne et al (2013).

There are two important considerations to respect at this stage; data is copied from the virtual community without any modification and subjective information retained. During this phase, it is possible to categorize individuals according to their degree of participation and commitment (Kozinets, 2002).

It is worth mentioning that data collection respected the data saturation principle.For more dataaccuracy and enrichment, we copied all the information related to the political messages posted by the candidates. After data collection, we proceeded to its analysis.

Data collection was collected manually to study the presence of political candidates on Facebook, the number of fans, the type of account used, the type of content posted and the reactions of citizens on the different Facebook pages of political candidates. Everything was copied from the local language of the country and translated and placed in an Excel sheet Kietzmann, et al. (2011).

In the first stage, we followed and observed all the posts on Facebook pages of five candidates during the 41 days before the final presidential elections of 2019. From the date of the beginning of the election campaigns, we collected 2850 posts. There were no ethical problems in collecting and analyzing the content of the posts. With respect to the ethical guidelines required in Internet research (Markham & Buchanan 2012), the study data was collected exclusively from candidates' profiles and public pages during an election period, which by their nature were not intended to be personal or private communications but rather public information intended to be disseminated and shared to the public Gil De Zuniga (2009).

Data Analysis Method

For the data analysis method, the authors followed the main steps of qualitative analysis, namely data transcription, information coding, and data processing (Andreani & Conchon 2005).

For data transcription, the authors relied on a qualitative data analysis, which was done manually (Silverman 1999). The authors copied and transcribed the collected data into "verbatims". In the case of non-participatory netnography, transcription is done by "copy and paste", there is no oral data to transform into text. It is therefore a concomitant step to datacollection. This is the case in our study Paveau, (2017).

Coding and processing of qualitative data.

Data coding "describes, classifies and transforms the raw qualitative data according to the analysis grid" (Andréani & Conchon 2005). This grid can be designed in several ways. The first consists in adjusting and shaping it with reference to the collected data ("open coding"); the second consists in defining it before the data is collected ("closed coding"). This choice of manual analysis without recourse to software is designed to be time-consuming, yet it suits the aims of the present study Markowitz-Elfassi (2019).

The authors observed the use of Facebook by the presidential candidates through their presence, posts, types of accounts, fans, vividness and topicsraised,subsequently identifying offline commitment. Thus, offline political commitment is measured by the number of likes, comments and shares of citizens. Finally, the link with online commitment (voting results) is identified. To this end, a content analysis was conducted in four phases. In the first phase, the authors monitored the presence and posts of each Stetka (2019) candidate on Facebook and collected all the information in a table in order to identify the effect on political commitment (online and offline). In the second phase, we determined the type of Facebook account used that generated the most commitment (online and offline). In the third phase, the number of fans was studied to explore its effect on political commitment (online and offline) Harris Heather et al., (2019). In the fourth phase, the authors analyzed the effect of content (videos, text, photos, language) on citizen commitment (online and offline). Each post was recorded in terms of type of content and effect on citizen political commitment (online and offline). Additionally, data collected from the posts and shared on Facebook was analyzed to look for Mercanti-Guérin (2010) elements of Aristotelian persuasion language (Green, 2004) and then to identify the type of information most used by politicians on their Facebook pages. Each post was coded under the most salient element, reflecting the main message conveyed in the post. The final step in the analysis is to search for themes or topics that appear in the collected posts Oviedo-García et al., (2014)

Results and Analysis

The results allowed us to identify the following factors:

1st Factor: The Presence of Political Candidates on Social Networks

Two candidates who have a strong presence on social networks and the highest number of publications are those of Mr. Kais Saied (by supporters) and Mr. Nabil Karoui with respectively 868 and 623 posts. We can also deduce that presence on social networks and success of a digital electoral campaign directly influenced offline political commitment of citizens. This is mainly represented by the results of the presidential elections which allowed Mr. Kais Saied to obtain most of the votes in the first and second rounds. These results are consistent with Lin's (2017) which showed that social media is a fast and effective way that political candidates can use to foster citizen support and commitment for their campaigns. Most political candidates use Facebook, as it is considered the most official type in an election campaign (Thomson 2006).

2nd Factor: Type of Facebook Account

The results indicate that subscribers and citizens favor interacting with each other within a group and not on the official and public pages of politicians. We can cite the example of a group created by citizens to support the candidate Mr. Kais Saied (current president of the republic). This group contains the highest number of postsand a large number of members reaching 200k.

These results refer to the notion of "citizen-initiated campaign" developed by Gibson (2015). This author showed that the "citizen-initiated campaign" is based on user-generated Facebook content and online mobilization. Organization of this type of campaign revolves around a citizen initiative. Then, use of this group has a significant effect on the voting decision of citizens, which is a direct result of the political commitment of citizens (Anne 2010).

The authors found that type of Facebook account used by the candidate is also related to his or her electoral outcomes. Specifically, the candidate with a citizen-run Facebook group tends to have both a higher vote share than candidates with other types of Facebook accounts. The president-elect's campaign is built around a voluntary citizen initiative which played a major role. The Facebook group of citizen supporters has more effect than a candidate's official page Paveau, (2010).

3rd Factor: Number of subscribers

The results indicate that the three candidates with the most subscribers are the first on the list with 410k, 400k and 200k respectively, consistent with the results of Lin (2017) which suggest that there is a relationship between the number of subscribers to candidates’ accounts and election results. According to the literature, voting is the most cited form of political commitment of citizens. Moreover, it is considered the clearest way through which citizens expresses their opinions and election choices. It is still considered a preferred means of expression (Anne, 2017) Table 2.

| Table 2 Number of Subscribers and the Number of Posts on Facebook of the top five Presidential Candidates | |||

| Candidates | Nbr Subscribers | Nb Posts | Average daily posts |

| Kais saied (a FB group created by sopperters) |

200k | 868 | 21.1 |

| Nabil karoui | 410K | 623 | 15 |

| Abdelfattah mourou | 118k | 190 | 4.6 |

| Youcef Chahed | 400k | 203 | 4.9 |

| Lotfi M‘raihi | 190k | 150 | 3.7 |

The two candidates who made it to the second round were the ones who posted the most on FB with the highest post rates per day Cogburn (2011).

4th factor: Type of content shared: Aristotelian language used by candidates

In our study, we referred to Steuer (1992), English et al. (2011), Kietzmann et al. (2011) and Bene (2017) to examine the type of content shared by political candidates in Tunisia. Type of content refers to Aristotelian persuasion language Pascal (1994) and its four dimensions; Ethos, Pathos, logos and vividness Pletikosa Cvijikj (2013).

Dimensions of Aristotelian persuasion language

Tables 3 and 4 below report the results on the level of commitment according to the dimensions of Aristotelian persuasion language:

| Table 3 Level of Commitment According to the Dimensions of Aristotelian Persuasion Language | ||||

| Aristotelian dimensions | Number of posts | Commitment level | ||

| Nb of Reactions | Nb ofComments | NB of shares | ||

| Ethos | 751 | 4 680 k | 1 115 k | 0.797 k |

| Pathos | 1 576 | 14 256k | 1 842 k | 1 097 k |

| Logos | 523 | 3 966 k | 0.196 k | 0.102 k |

| Table 4 Verbatim Representing Aristotelian Persuasion Language | |||

| Dimensions of persuasion language | Message content | Frequency | Verbatim |

| Ethos | Credibility | 171 | "I went to the best colleges in the business." C2 "My successes in my professional field allow me to lead the country successfully." C4 "I am a university professor and I represent most of the citizens" C1 "I founded one of the most successful companies in the field of media and marketing" C2 "My wife is brilliant in her field, she has contributed to my success and she has always supported me" C2 "I am active in civil society" C3 "I contributed to the revolution" C5 |

| Personal information (education/professional life professional background) |

223 | ||

| Family and private life | 15 | ||

| Political activities and achievements | 307 | ||

| Pathos | Emotional call | 933 | "I will fight poverty" C2 "The revolution is ours, it is our youth, our men and women" C4 It looks like us. "I will not allow anyone to be deprived of their most basic rights in life" C1 "We are all for a better future" C3 "There is no talent without ambition" C5 "A courageous president" C2 "I will be a president responsible for his people" C1 |

| Relationship between the candidate and his/her audience | 275 | ||

| Motivational call | 82 | ||

| Sense of identity of Public |

182 | ||

| Personal interests of the public | 104 | ||

| Logos | Use of numbers and statistics | 318 | "Collective facilities and industrial areas with the aim of developing the interior regions and ensuring regional balance" C1 "Sharing of poverty, growth and unemploymentrates" C2 Sharing of documents to justify political positions C3 |

| Posting documents and factual information | 205 | ||

Use of Pathos as a way to present a more personal approach is the most used dimension by politicians in Tunisia. The Facebook pages examined in this study show the use of emotional or motivational tactics whichwere particularly important to foster political commitment among citizens in Tunisia.

The results of our study showed first the importance of emotional appeal which is intended to convince the public by creating a link between the politician and the public, this is explained by the high level of commitment of citizens towards this type of posts. With Pathos, there are more reactions, more comments and more shares. Our results are consistent with those of Bronstein (2013) who confirmed that the use of pathos in the Facebook pages of Obama and Romney during the 2012 US presidential election, allowed the candidates to tap into the emotions of their audience, with the aim of creating emotional alliances with them that will allow them to maintain their support. In another study of the 2012 U.S. presidential election, Justinussen (2015) asserted that the use of all three dimensions impacted the level of user commitment and that emotion-based language dominated much of the campaign on Facebook. These findings echo previous studies that examined politicians' use of Facebook (Bar-Ilan et al., 2015; Samuel-Azran et al., 2018) in which pathos also prevailed in online political communication primarily as an attempt to create an emotional bond with users.

Vividness

Vividness is characterized by image, text, and video. Table 5 below presents the vividness of the messages posted by the candidates Kunz, (2017):

| Table 5 Use of Vividness in Politician’s Posts | ||||||||

| Posts | Reactions | Comments | Shares | Average reactions per post | Average comments per post | Average shares per post | ||

| Photos | 1 510 | 8 023k | 940.16k | 540k | 7.1k | 0.62k | 0.35k | |

| Videos | 1 130 | 13 892k | 2 114k | 1 389.2k | 12.29k | 1.87k | 1.22k | |

| Text | 210 | 987k | 98.7k | 67.2k | 4.7k | 0.47k | 0.32k | |

Our results indicate that political candidates in Tunisia share more photos and videos than text.

When Tunisian candidates included photos in their posts, the number of likes increased and comments on the posts were more personal in nature. In addition, adding videos resulted in even more likes and shares. Thus, videos generated more political commitment from citizens with 13,892k likes, 2,114k comments and 1,389.2k shares. At the same time, for photos, there were 8,023K reactions, 940.16K comments and 540K shares. For text, the reactions are lower, namely 987 K of reactions, 98.7 K of comments and 67.2 K of shares.

These results agree with those of Kruikemeier et al. (2013); Xu & Sundar (2014), who found that high content vividness can potentially attract voters and increase their commitment with relevant content. The authors identified the topics that mostly engaged citizens politically. The results are presented in Table 6.

| Table 6 Level of Commitmentby Topic | |||||

| Nbr of | Commitment level | Verbatim | |||

| Post topic | posts | Reactions | Comments | Shares | |

| Economy | 350 | 11 082k | 1 230k | 998k | "We are working to develop the social and solidarity economic sector, so that civil society can contribute to the financing of development, economic activity and social solidarity. |

| Education | 120 | 73k | 30k | 12k | "Ensure a high quality of education" C5 "Improving schools in rural areas" C2 "Digitizing all schools" C4 "Updating educational programs" C3 |

| Elections | 520 | 410k | 20k | 70k | "Elections are manifestations of democracy in Tunisia" C4 "Elections are a popular right that we have obtained thanks to the revolution "C3 |

| Party | 230 | 180k | 400k | 32k | "It is the party closest to the people" C2 "We are the voice of the people "C2 "We are the party that defends modern Tunisian women"C3 |

| Politician | 190 | 320k | 240k | 43k | "I went to the best colleges in the business." C2 "My successes in my professional field allow me to lead the country successfully." C4 "I am a university professor and I represent most of the citizens" C1 |

| "I founded one of the most successful companies in the field of media and marketing" C2 "I am active in civil society" C3 "I contributed to the revolution" C5 |

|||||

| Security | 620 | 1 800k | 351k | 126k | "We must fight against terrorism "C4 "Terrorism does not represent us "C3 |

| Society | 737 | 8 720k | 827k | 674k | "Our young graduates are unemployed, we need to work on that. Lowering unemployment rates is our first priority" C1 Strengthen assistance to poor families. "The poorest are also Tunisian citizens" C2 "The Tunisian woman is the pioneer of this society. She is our pride. Equality between men and women, it must be legitimate "C3 |

| "Introduce a supplementary solidarity system to support the pension scheme. C4 | |||||

| Call for involvement | 83 | 317k | 75k | 41k | "Don't give up on your right to vote. We expect your support." C5 |

| TOTAL | 2850 | 22 902k | 3 153k | 1 996k | |

Six categories of topics are discussed in a presidential election campaign and posted on the social media pages of political parties and politicians (Adams & McCorkindale, 2013; Aharony, 2012; Bronstein, 2013; Ceccobelli & Cotta, 2016; Justinussen, 2015; Larsson, 2017). These are economy, education, elections, party, politician, security, society, and call for involvement.

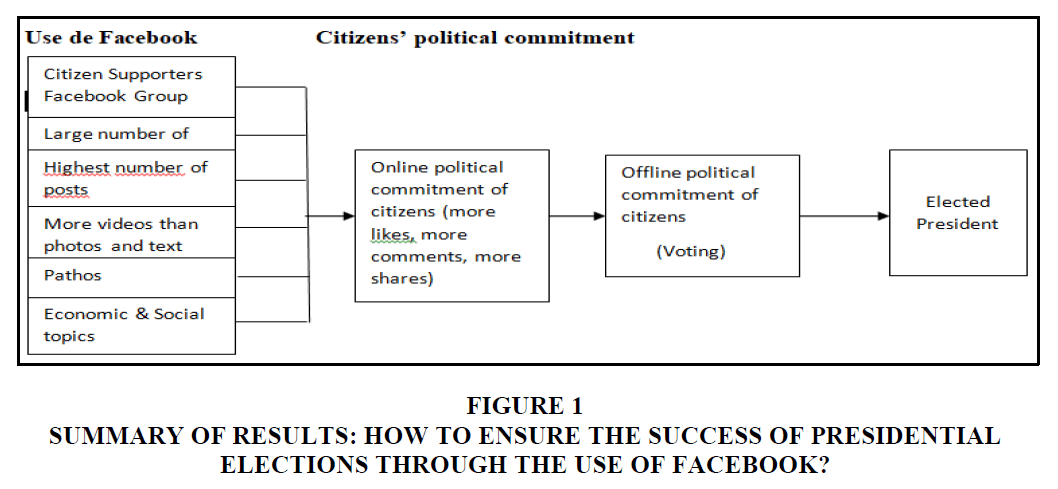

Our results indicate that the candidates' economic posts have the highest number of citizen commitment, showing that citizensare particularly sensitive to this dimension. The candidates mentioned investment and development of the internal regions, which generated positive reactions. Moreover, the social dimension has generated a very important level of citizen commitment. The word unemployment is mentioned in the posts and has created an effect, a theme that touches on the needs of representative targets of the population. Xue (2014) found similar results when examining the Facebook pages of Japanese politicians and indicated that sharing information on areas such as economy, society, and security has an impact on citizens' political commitment. Figure 1, below summarizes the results.

Figure 1 Summary of Results: How to Ensure the Success of Presidential Elections Through the use of Facebook?

Managerial Implications

The implications of this study should interest politicians who wish to ensure the political commitment of citizens by using Facebook in their electoral campaign as well as to communication agencies that have to establish a communication strategy for politicians.

Table 7 below summarizes our implications.

| Table 7 Management Involvement | |

| Interest of using FB in an election campaign | The candidate must be present in social networks. FB, a media not to be neglected in political communication. It has proven itself in the world. |

| What type of account? | Have a Facebook group or groups created by citizen supporters and not directly affiliated with the candidate. |

| Don't just use a personal account to exchange with citizens about yourself. | |

| Be in contact with the administrators of the online and offline groups. | |

| How often? | The candidate keeps an eye on their competitors and must ensure that they have more posts than they do. |

| What language is used? | To use a speech where there is emotion (pathos). The citizen is emotional and reactive to this kind of speech and less to ethos and logos. |

| Speak the language of the citizen and take into consideration their needs and expectations | |

| Which vividness to choose? | Use content in the form of videos and pictures on the actions and events carried out. |

| Which topics to talk about first | Choose topics that reach the representative target of voters and not a niche. |

| Focus on economic and social topics. | |

Conclusion

This study examined the effect of political candidates’ use of Facebook on citizen commitment. This study presented theoretical, empirical and managerial contributions.

Theory-wise, our study contributed to the previous literature of political marketing, by the fact of combining at the same time four different dimensions of Facebook use as a political platform during an election period. These different dimensions highlight different aspects of this use such as presence on social networks, type of account used, the number of subscribers and posts and the content shared. There also is an emphasis on the language used in the messages, the different types of information presented such as videos, pictures and text and the topics raised. The combination of these dimensions revealed the importance of Facebook as a political platform to channel politicians' communication strategies with their public and disseminate information.

Our study also presents an empirical contribution. Indeed, to our knowledge, no previous study in political marketing has combined all the dimensions of presence, type of account, number of subscribers and posts and type of content (language, vividness and topics), to examine their effect on citizens' political commitment during an online and offline presidential election campaign.

The notion of citizen commitment deserves further development. Our study opens up several future research venues. First, there is a need to further substantiate our results by expanding the sample to include all politicians. We propose to conduct a quantitative study in order to generalize our results. An online survey administered to all potential voters should be considered. Examining other factors of commitment is also recommended in order to generalize our results.

Second, our study focused on the candidate's presence, their posts (vividness, topics and language). Then, it is interesting that a future study tests the effect of social media use on the political commitment of citizens focusing on the socio-demographic characteristics of candidates.

Third, our study focused on Facebook. Therefore, it is important to consider other social networks such as instagram, youtube, tweeter, and test their effects on citizens' political commitment.

References

Adams, A., & McCorkindale, T. (2013). Dialogue and transparency: A content analysis of how the 2012 presidential candidates used Twitter. Public relations review, 39(4), 357-359.

Aharony, N. (2012). Twitter use by three political leaders: an exploratory analysis. Online information review.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Ahlqvist, T., Bäck, A., Heinonen, S., & Halonen, M. (2010). Road‐mapping the societal transformation potential of social media. foresight.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref,

Algesheimer, R., Dholakia, U. M., & Herrmann, A. (2005). The social influence of brand community: Evidence from European car clubs. Journal of marketing, 69(3), 19-34.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Andreani, J.C., & Conchon, F. (2005). Reliability and validity of qualitative surveys. A state of the art in marketing. French review of marketing, (201).

Barger, V., Peltier, J. W., & Schultz, D. E. (2016). Social media and consumer engagement: a review and research agenda. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Becker, S., Bryman, A., & Ferguson, H. (Eds.). (2012). Understanding research for social policy and social work: themes, methods and approaches. policy press.

Bene, M. (2017). Go viral on the Facebook! Interactions between candidates and followers on Facebook during the Hungarian general election campaign of 2014. Information, Communication & Society, 20(4), 513-529.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Bossetta, M. (2018). The digital architectures of social media: Comparing political campaigning on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat in the 2016 US election. Journalism & mass communication quarterly, 95(2), 471-496.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Brodie, R. J., Ilic, A., Juric, B., & Hollebeek, L. (2013). Consumer engagement in a virtual brand community: An exploratory analysis. Journal of business research, 66(1), 105-114.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Bronstein, J. (2013). Like me! Analyzing the 2012 presidential candidates’ Facebook pages. Online Information Review.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Bronstein, J., Aharony, N., & Bar-Ilan, J. (2018). Politicians’ use of Facebook during elections: Use of emotionally-based discourse, personalization, social media engagement and vividness. Aslib Journal of Information Management.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Ceccobelli, D., & Cotta, B. (2016). Leaders'‘Green’Posts. The Environmental Issues Shared by Politicians on Facebook. European Policy Analysis, 2(2), 68-93.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Chahal, H., & Rani, A. (2017). How trust moderates social media engagement and brand equity. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Cogburn, D. L., & Espinoza-Vasquez, F. K. (2011). From networked nominee to networked nation: Examining the impact of Web 2.0 and social media on political participation and civic engagement in the 2008 Obama campaign. Journal of political marketing, 10(1-2), 189-213.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Dessart, L., Veloutsou, C., & Morgan-Thomas, A. (2015). Consumer engagement in online brand communities: a social media perspective. Journal of Product & Brand Management.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

English, K., Sweetser, K. D., & Ancu, M. (2011). YouTube-ification of political talk: An examination of persuasion appeals in viral video. American Behavioral Scientist, 55(6), 733-748.

Gerodimos, R., & Justinussen, J. (2015). Obama’s 2012 Facebook campaign: Political communication in the age of the like button. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 12(2), 113-132.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Giasson, T., Darisse, C., & Raynauld, V. (2013). Politique PQ 2.0: qui sont les blogueurs politiques québécois? Politique et sociétés, 32(3), 3-28.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Gibson, J. L., Caldeira, G. A., & Spence, L. K. (2003). Measuring attitudes toward the United States supreme court. American Journal of Political Science, 47(2), 354-367.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Gibson, R. K. (2015). Party change, social media and the rise of ‘citizen-initiated’campaigning. Party politics, 21(2), 183-197.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Gil De Zuniga, H., Puig-I-Abril, E., & Rojas, H. (2009). Weblogs, traditional sources online and political participation: An assessment of how the Internet is changing the political environment. New media & society, 11(4), 553-574.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Green, M. C., Brock, T. C., & Kaufman, G. F. (2004). Understanding media enjoyment: The role of transportation into narrative worlds. Communication theory, 14(4), 311-327.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Harris Heather E. and Kimberly R. Moffitt (2019), Michelle Obama and Flotus effect : plateform, presence and Agency, Rowman et Littlefield.

Harris, L., & Harrigan, P. (2015). Social media in politics: The ultimate voter engagement tool or simply an echo chamber?Journal of Political Marketing, 14(3), 251-283.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Hinson, R., Boateng, H., Renner, A., & Kosiba, J. P. B. (2019). Antecedents and consequences of customer engagement on Facebook: An attachment theory perspective. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 13(2), 204-226.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref,

Hollebeek, L. (2011). Exploring customer brand engagement: definition and themes. Journal of strategic Marketing, 19(7), 555-573.

Hollebeek, L. D., & Chen, T. (2014). Exploring positively-versus negatively-valenced brand engagement: a conceptual model. Journal of Product & Brand Management.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Keat, L. E. N. G. (2012). Marketing politicians on facebook: An examination of the Singapore general election 2011. Studies in Business & Economics, 7(1).

Kiesler, C. A. (1971). The psychology of commitment: Experiments linking behavior to belief.

Kietzmann, J. H., Hermkens, K., McCarthy, I. P., & Silvestre, B. S. (2011). Social media? Get serious! Understanding the functional building blocks of social media. Business horizons, 54(3), 241-251.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Koc-Michalska, K., & Lilleker, D. (2017). Digital politics: Mobilization, engagement, and participation. Political Communication, 34(1), 1-5.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Kozinets, R. V. (2002). The field behind the screen: Using netnography for marketing research in online communities. Journal of marketing research, 39(1), 61-72.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Kruikemeier Sanne , Noort Guda van , Vliegenthart Rens and DeVreese Claes H (2013), « Getting closer: The effects of personalized and interactive online political communication Show less », European Journal of Communication, 28 (1), 53-66.

Kunz, W., et al., (2017). Customer engagement in a big data world. Journal of Services Marketing.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Larsson, A. O. (2017). Going viral? Comparing parties on social media during the 2014 Swedish election. Convergence, 23(2), 117-131.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Leckie, C., Nyadzayo, M. W., & Johnson, L. W. (2016). Antecedents of consumer brand engagement and brand loyalty. Journal of Marketing Management, 32(5-6), 558-578.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Leston-Bandeira, C., & Bender, D. (2013). How deeply are parliaments engaging on social media? Information Polity, 18(4), 281-297.

Lin, H. C. (2017). How political candidates' use of Facebook relates to the election outcomes. International Journal of Market Research, 59(1), 77-96.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Mangold, W. G., & Faulds, D. J. (2009). Social media: The new hybrid element of the promotion mix. Business horizons, 52(4), 357-365.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Markowitz-Elfassi, D., Yarchi, M., & Samuel-Azran, T. (2019). Share, comment, but do not like: The effect of politicians’ facial attractiveness on audience engagement on Facebook. Online Information Review.

Indexed at, , Google Scholar, Cross ref

Mercanti-Guérin, M. (2010). Facebook, un nouvel outil de campagne: Analyse des réseaux sociaux et marketing politique. La revue des Sciences de Gestion, (2), 17-28.

Oviedo-García, M. Á., Muñoz-Expósito, M., Castellanos-Verdugo, M., & Sancho-Mejías, M. (2014). Metric proposal for customer engagement in Facebook. Journal of research in interactive marketing.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref,

Pansari, A., & Kumar, V. (2017). Customer engagement: the construct, antecedents, and consequences. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45(3), 294-311.

Pascal, P. (1994). Political engagement: decline or mutation.Presses de Sciences Po.

Paveau, M.A. (2017). Digital discourse analysis. Dictionary of forms and practices. Hermann.

Paveau, M.A., & Gadet, F. (2010). Discourse theory: fragments of history and criticism. Franche-Comté University Press.

Pletikosa Cvijikj, I., & Michahelles, F. (2013). Online engagement factors on Facebook brand pages. Social network analysis and mining, 3(4), 843-861.

Safiullah, M., Pathak, P., Singh, S., & Anshul, A. (2017). Social media as an upcoming tool for political marketing effectiveness. Asia Pacific Management Review, 22(1), 10-15.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Smith, B. G., & Gallicano, T. D. (2015). Terms of engagement: Analyzing public engagement with organizations through social media. Computers in human Behavior, 53, 82-90.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Stetka, V., Surowiec, P., & Mazák, J. (2019). Facebook as an instrument of election campaigning and voters’ engagement: Comparing Czechia and Poland. European Journal of Communication, 34(2), 121-141.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Steuer, J. (1992). Defining virtual reality: Dimensions determining telepresence. Journal of communication, 42(4), 73-93.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Sun, J., Wang, G., Cheng, X., & Fu, Y. (2015). Mining affective text to improve social media item recommendation. Information Processing & Management, 51(4), 444-457.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Thomson, M. (2006). Human brands: Investigating antecedents to consumers’ strong attachments to celebrities. Journal of marketing, 70(3), 104-119.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Vaccari, C. (2013). Digital politics in Western democracies: A comparative study. JHU Press.

Vaccari, C., Chadwick, A., & O'Loughlin, B. (2015). Dual screening the political: Media events, social media, and citizen engagement. Journal of communication, 65(6), 1041-1061.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Wen, W. C. (2014). Facebook political communication in Taiwan: 1.0/2.0 messages and election/post-election messages. Chinese Journal of Communication, 7(1), 19-39.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Wojcieszak, M. E., & Mutz, D. C. (2009). Online groups and political discourse: Do online discussion spaces facilitate exposure to political disagreement? Journal of communication, 59(1), 40-56.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Xu, Q., & Sundar, S. S. (2014). Lights, camera, music, interaction! Interactive persuasion in e-commerce. Communication Research, 41(2), 282-308.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Yarchi, M., & Samuel-Azran, T. (2018). Women politicians are more engaging: male versus female politicians’ ability to generate users’ engagement on social media during an election campaign. Information, Communication & Society, 21(7), 978-995.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Zhang, Y. J. (Ed.). (2006). Semantic-based visual information retrieval. IGI Global.

Received: 26-May-2022, Manuscript No. AMSJ-22-12086; Editor assigned: 30-May-2022, PreQC No. AMSJ-22-12086(PQ); Reviewed: 13-Jun-2022, QC No. AMSJ-22-12086; Revised: 28-Jun-2022, Manuscript No. AMSJ-22-12086(R); Published: 04-Jul-2022