Research Article: 2019 Vol: 23 Issue: 2

The Effects of Scandal on Corporate Image and Purchase Intention Perspectives from Consumers

Zhuofan Zhang, University-Kingsville

Ruth Chatelain-Jardon, University-Kingsville

Jose Luis Daniel, University-Kingsville

Abstract

What are the effects of a scandal on organizational results? How does a socially irresponsible behavior event affect organizational financial performance, organizational image, and consumers’ purchase intentions? Does a scandal lead to a decline in these organizational outcomes? Does the proximity to the end-consumer influence how a scandal affects the organizational results? Previous studies have shown inconclusive results for the relationship between Corporate Social Performance (CSP) and financial performance. This study hypothesizes that scandals have a negative impact on the image and performance of organizations. Moreover, it is expected that irresponsible corporate behaviors negatively affect consumers’ purchase intentions. Results show a significant difference in corporate image, financial performance, and consumers’ purchase intentions between organizations facing scandal conditions and those in non-scandal conditions, regardless of the company’s position in the supply chain. Conclusions and implications are discussed.

Keywords

Corporate social responsibility, Scandals, Corporate image, Financial performance, Purchase intentions.

Introduction

Corporate Social Performance (CSP) is a relatively new term; Wood noted that the term “refers to the principles, practices, and outcomes of businesses’ relationships with people, organizations, institutions, communities, societies, and the earth” (Wood, 2016). The classical term of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) has been incorporated as one of the elements of CSP because of its “ethical and/or structural principles of social responsibility, or business engagement with others” (Wood, 2016). Recent CSP research copes with the idea that businesses play a beneficial social role in their environment, even though their ultimate goal is to achieve superior financial performance. As part of CSP, organizations conduct social activities such as supervising the quality and safety of products and actively engaging in scandal management in order to maintain a good relationship with the end customer and, ultimately, access to potential revenue. These activities vary depending on the firm’s resources and access to credit. Along these lines, Guo and Luo (2017), noted that organizations present idiosyncratic productivity levels and, in many cases, are constrained by credit.

It is important to note that the actions performed by an organization under the CSP umbrella may be the result of “deliberate actions of businesses toward these stakeholders as well as the unintended externalities of business activity” (Wood, 2016). Thus, dealing with negative corporate events/behaviors intended or unintended by the organization may lead to damaging the relationship with the end consumer and may affect access to the potential revenue stream. However, the body of research in this regard is inconclusive. For example, Moskowitz (1972), found a negative or null relationship between CSP and organizational financial performance. On the other hand, Graves and Waddock (1994) reported a positive connection between these two concepts. Thus, the contradictory results may be allocated, in some cases, to the visibility or proximity of the organization to the end consumer. The purpose of this study is to examine whether the visibility/proximity of the organization to the end consumer affects the results of influence of CSP over corporate image, financial performance, and consumers’ purchase intentions when an organization faces a scandal. This research aims at answering the following research questions:

1. Does scandal negatively impact corporate image?

2. Does scandal negatively impact corporate financial performance?

3. Does scandal negatively impact consumers’ purchase intentions?

Specifically, this study aims to demonstrate that a negative organizational event (scandal) will have the same effects on the organizational outcomes (organizational image, financial performance, and consumers’ purchase intentions) of a manufacturer, when compared to the effects on a retailer’s organizational outcome. In other words, it is expected that there will be a difference in organizational outcomes between organizations facing a socially irresponsible behavior event (scandal) and those organizations in non-scandal conditions, regardless of the company’s position in the supply chain (visibility/proximity of the organization to the end consumer).

Literature Review

The Corporate Social and Financial Performance Link

The impact of Corporate Social Performance on firm financial performance has evoked much attention among scholars. According to Wood (1991), CSP can be defined as “a business organization’s configuration of principles of social responsibility, processes of social responsiveness and policies, programs and observable outcomes as they relate to the firm’s societal relationships” (Wood, 1991). The integrated corporate social performance model was first developed as a system integrating both economic, ethical, and legal elements (Carroll, 1979) and was then advanced by combining action (social responsiveness) perspectives and factors motivating action process in the revised CSP model (Wood, 1991).

Since CSP combines both social and corporate governance, which have societal influences, it is believed to be closely related to firm financial performance based on a wide variety of studies examining CSP’s economic impacts. However, the relationship between CSP and firm financial performance has been debated for decades. While a majority of studies have shown a positive relationship, some other studies have revealed a negative or no relationship between the two concepts (Graves and Waddock, 1994). For example, based on a regression analysis of 469 companies, Graves and Waddock contend that corporate social performance tends to have a long-term positive impact on financial performance due to institutional ownership and a firm’s tendency to maintain CSP investments. Later, Brown (1998) also found a positive relationship between social performance and stock market profitability from corporate reputation perspectives. The positive link between the two concepts is explained by a long-term sustainable social benefit generated by positive corporate social responsiveness (Hay et al., 1976). Enhancing CSP, for example, can raise consumer awareness about a firm’s social responsibility engagement and thus engender trust and a positive reputation in the long run. Moreover, CSP implies how firms manage their stakeholder relationships, and a more satisfactory stakeholder relationship will lead to a better long-standing financial performance (Donaldson & Preston 1995).

On the other hand, the empirical studies that support a negative influence on firm performance of CSP give opposing explanations. For example, Ullman (1985) has argued that corporate social responsiveness behavior generates additional costs that can put firms at an economic disadvantage. A firm’s socially responsible behavior can sometimes even hinder the financial goal and interfere with important managerial decisions.

However, some studies found no relationship between the concepts. McWilliams and Sigel (2001), point out the difficulty of measuring appropriate CSP actions and argue that these measures are dependent on the stakeholder demand as well as costs derived from additional social investments. Generally, this perspective highlights that the seemingly simple relationship of CSP and firm financial performance can be, in fact, much more complicated, as it is contingent on factors that influence the balance of social performance and financial performance from different stakeholders’ perspectives.

Though the relationship of CSP and firm financial performance remains uncertain, many firms believe it is still necessary to engage in socially responsible actions, as firms are regarded as social citizens and failing to do so will cause firms to increase financial loss. For example, the famous Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC) food safety scandal in China in 2006 resulted in an extremely negative public image and tremendous financial loss (dramatic decline in market sales) for the company. Though the misconduct came from KFC’s major suppliers–KFC later announced its appropriate inspection and strict assessment tests–KFC experienced a sudden drop of sales in a very short time. This example stresses the possibility of the financial loss and damaged social image coming from socially irresponsible behavior of certain companies and its spillover effect on their channel members.

With the example of KFC in China in mind, it is believed that factors that influence the relationship between CSP and firm financial performance have remained largely unexplored, and it is proposed that one key to this fundamental relationship is the customers’ awareness of an organization’s CSP in this context. This is because the social dialogue between customers and organizations represents a major part of how CSP is reflected as a social component in the market. Customers have expectations not only on organizational performance but also on social ethical behaviors. In fact, the positive impact of CSP on customer satisfaction has been identified as a source of competitive advantage for an organization (Porter & Kramer 2006). A robust body of research on customer expectation and satisfaction reported and emphasized that past customer experiences can cause variations of future customer expectations and satisfaction (Zeithaml et al., 1993). Unethical or socially irresponsible behavior by an organization can lead to a damaged reputation and be a danger signal able to deter financial performance and consumers’ purchase intentions. Therefore, for organizations building customer awareness of their good social behavior, engaging in CSP activities is an important way of establishing positive social dialogue, retaining customers, enhancing trust, and building a positive corporate social image.

It is important to note that not all organizations may be able to broadcast their CSP efforts. For some organizations, their CSP may not be visible enough to customers in order to achieve a beneficial (or detrimental in the case of a scandal) social dialogue. Even though open disclosure of CSP activities may be an effective way of making customers aware of organizational socially responsible behaviors, CSP efforts may not be visible to the customers because they may depend more heavily on the actual visibility or proximity of the organization to the end customer. For example, regarding the KFC case, the diminishing awareness of suppliers of KFC due to the lack of information accessibility created a misrepresentation of KFC’s CSP. Since KFC is the supply chain member interacting directly with the final customers in the whole supply chain, customers have more familiarity with KFC than with KFC’s suppliers. Even though KFC’s suppliers were responsible for the scandal, KFC suffered tremendous financial loss due to their visibility to the final customers. Therefore:

H1: Consumer’s evaluation of organizational financial performance will be negatively impacted by scandals, regardless of the organization’s position in the supply chain.

Signaling Theory

Signaling theory is concerned with the effective use of signals in social interactions; it studies the information flow and patterns from sender to receiver according to an evolutionary framework (Spence 1973). Signals are considered as the sender’s behavioral features that evolve with the purpose of impacting a receiver’s behavior patterns (Smith and Harper 2003). Thus, signals are produced to have specific effects on receivers. Signaling theory has been applied to the marketing field by modern scholars. They propose that organizational reputation is based on the accumulation of consistent signals, and it is expected that positive signals can improve organizational image/reputation. Indeed, signaling theory has been widely used in the marketing field. For example, Koslow (2000), reports that many organizations try to enhance customers’ brand awareness by sending visible signals through advertising and that consumers have adaptive responses to different advertising claims. Recent research also supports a positive relationship between corporate social responsibility and corporate performance. For example, Su et al. (2016) contend that CSR practices positively signal a firm’s financial performance in an institutional environment. Furthermore, Arikan et al. (2014) claim that corporate social responsibility positively leads to consumers’ purchase intentions and customer satisfaction through a mediation role of corporate reputation. Applying signaling perspectives, Alon and Vidovic (2015) examine how sustainability, performance, and assurance increase corporate reputation.

Previous research has examined the relationship between signaling and CSP in attracting stakeholders and states that potential stakeholders receive CSP information as signals for interpretation and that the interpretation of CSP can be fundamental to their overall perception of the organization (Greening & Turban 2000). Thus, CSP could be considered as an attractive tool to signal stakeholders about the organization’s future potential. In order to maximize the social benefits and influences, it is suggested that firms disclose as many positive social actions as possible to the public (Campbell, 2001). Because signals have the function of conveying information and helping frame the predictions of customers as a consequence, signals have an effect on customers’ later responses to organizational socially responsible or irresponsible behavior (Krebs, 1984).

It is important to note that the signals transmitted from senders to receivers are not only dependent on the traits of senders, but they also depend on the receiver’s own characteristics since both senders and receivers are facilitating the transmission process (Krebs, 1984). Information asymmetry is an important condition for signaling theory to apply; consequently, the effectiveness of the process is based on whether the signal meaning can be successfully conveyed and comprehended by receivers (Fearon, 1997). For example, senders can benefit from sending information when transmitted signals successfully reach receivers who have accessibility to the information; as a result, receivers can have a future reaction. Within a CSP context, customers need information accessibility to interpret the positive social practice signals sent by organizations in order to generate awareness and a positive response afterwards. The effectiveness of signal transmission may differ based on the communication channels used or available in the market. Hence, some organizations may transmit socially responsible or irresponsible behavior more effectively than others, and customers’ responses to those behaviors will vary according to the quality of signal transmission.

The Visibility of Members in the Supply Chain

Management of the supply chain involves the exchange of information among members. In a supply chain, every member is linked to other members in an upstream or downstream way; an upstream member needs to receive orders from a downstream member to start the manufacturing process. It is a widely accepted concept that an upstream member is any organization in which activity precedes the production/transformation of the product, while a downstream member is any organization in which a value-creating activity is performed after the production. According to Ayers & Odegaard, “upstream relates to operations that precede point of reference . . . and downstream operations, on the other hand, follow points of reference” (Ayers & Odegaard 2008). As an illustration for this conceptualization, distributors are downstream members of manufacturers and upstream members of retailers.

Every channel member has a specific role in the supply chain, regardless if they are upstream or downstream members. There are three main supply chain roles in a basic supply chain model: manufacturers, distributors, and retailers. In a more sophisticated and widely used model, the four-agent model developed by Forrester (1961), four roles (manufacturer, distributor, wholesaler, and retailer) have been identified as the members of a simple supply chain. In general, the definition of roles in the supply chain varies according to the business function of the supply chain member. For example, a retailer’s supply chain has five basic roles/agents: supplier, manufacturer, distributor, retailer, and consumer. For the purpose of this study, this retailer supply chain model has been adopted as the research focus. Please note that all the members of the supply chain produce value aimed at catering to the end customers’ needs/requirements. Thus, the visibility of each organization (channel member) to the end consumer is determined by the proximity of the supply chain member to the final customer.

In a customer-oriented supply chain, all the organizations involved in the supply network have the ultimate goal of reaching and satisfying end consumers; however, the consumers’ information access to each member is different; retailers have dominant capability of information transmission due to their proximity (position located right next to the end consumers). On the other hand, suppliers sit in a less important position in the channel regarding information communication. Signaling theory proposes both the impact of positive and negative signals on customers’ perceptions (Rao & Reukert 1994). So, while consistent positive signals can potentially enhance the firm’s corporate image, negative signals can harm the organization’s reputation and image and are believed to be detrimental to organization’s financial performance. As a consequence, it is expected that negative signals will have a negative impact regardless of the company position in the supply chain. It is important to note that even though CSP-related marketing activities are typically interpreted as positive signals, firms cannot avoid some negative signals emerging from irresponsible social practices such as scandals, which can negatively affect organizational image and financial performance.

Consistent with signaling theory, which suggests that the senders’ signals indicate their behavior patterns, spillover effect of socially irresponsible corporate behavior will strongly influence the receiver’s perspective of the senders’ behavior patterns (Smith & Harper 2003). This scenario represents important implications for the organization since it will influence consumers’ purchase intentions. According to Mohr et al. (2001), corporate social responsibility has a strong influence over consumers’ purchasing intentions. They note that consumers are more likely to boycott companies that conduct irresponsible behavior. On the same path, Mohr and Webb (2005), also studied the influence of corporate social responsibility on consumers’ purchase intent and compared it to the impact of price over consumers’ purchase intentions. Interestingly, they report that social responsibility has a stronger impact on purchase intentions than a low price. Finally, Sen and Bhattacharya (2001) found that a lack of social responsibility initiatives could decrease consumers’ intentions to buy products. Thus, the following hypotheses are presented:

H2 Consumer perspectives on organizational overall corporate image will be negatively impacted by scandals, regardless of the organization’s position in the supply chain.

H3 Consumer’s purchase intention of organizational products will be negatively impacted by scandals regardless of the organization’s position in the supply chain.

Spillover Effect on Channel Members

According to Robson, spillover effect, from an economist’s perspective, refers to the idea that “public policies in one jurisdiction necessarily have effects that significantly affect others” (Robson, 1998). Spillover effect is widely used in marketing literature to explain the risk of product line extension, umbrella branding, market entrance, etc. For example, Roehm and Tybout (2006), explain how scandals may exert spillover effect positively or negatively on competitors’ products. Competitors’ products can be impacted negatively if the scandalous event suggests a possible “association” with other brands in the same product category. This study clearly indicates the importance of considering the relevance of “association” between two parties when examining the direction and strength of spillover effect. Based on the notion of “association,” it can be argued that the supply chain members are closely associated with each other as a result of delivering the products through the supply channels. Because of such connections, people might assume other related companies may have the same practices as the company conducting socially irresponsible behavior, especially if they share the same channels. Consequently, other channel members cannot be deemed as “innocent” if one company is involved in socially irresponsible corporate behavior (e.g., scandals).

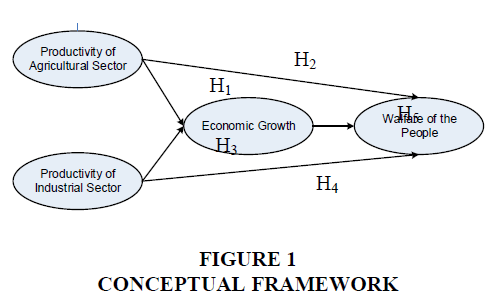

In summary, it has been hypothesized that irresponsible corporate behaviors (scandals) would negatively influence the organizational image, financial performance, and consumers’ purchase intentions since, according to signaling theory, these negative signals (unethical behavior) sent by the organization will cause the receiver (customer) to form his or her perspective of the organization’s future potential.

Please note that even though the proximity of the channel member to the end customer may influence the visibility of the organization and hence increase or decrease the potential damage caused by the scandal, it is considered that spillover effect would be able to neutralize the visibility/proximity of the channel member. The model for this study is presented in Figure 1.

Methodology

The purpose of this study is to examine whether the visibility/proximity of the organization to the end consumer affects the result of CSP on corporate image, financial performance, and consumers’ purchase intentions when an organization faces a scandal. It is expected that there will be a difference in organizational outcomes between organizations facing a socially irresponsible behavior event (scandal) and those organizations in non-scandal conditions, regardless of the company’s position in the supply chain (visibility/proximity of the organization to the end consumer).

Experiment

Given the specifications of this study, experimentation was required. The study was conducted in a controlled setting in a university lab. A total of 113 undergraduate students from a mid-western university participated in a four-condition experiment. Table 1 presents the dimensions for scandal and no-scandal.

| Table 1 Dimensions for Scandal and No-scandal | ||

| Dimensions | Scandal | No-scandal |

| Manufacturer | Scandal faced by Manufacturer | No-scandal faced by Manufacturer |

| Retailer | Scandal faced by Retailer | No-scandal faced by Retailer |

Participants were randomly assigned to one of the four conditions. To manipulate scandals, a company scenario was selected that involved either scandals or no scandals. In the scandal condition, participants were informed that the manufacturer was involved in hiring refugee children to make clothing for their major factories. In the non-scandal condition, participants were informed that the manufacturer followed normal operation, conforming to government regulations. To manipulate supply chain members’ proximity, participants were either assigned to a manufacturer (upstream member) or to a retailer (downstream member) condition. After evaluating the scenarios, participants answered a questionnaire containing dependent measures and demographic questions.

Instrument

The instrument measured three constructs: organizational image, organizational performance, and customers’ purchasing intentions. The latent variables had three indicators; they all used a 1-7 Likert-type scale and acceptable reliability measures were found. The following table shows one item per construct, the scale used, and the corresponding Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. Table 2 presents the constructs and their correspondent Cronbach’s alpha.

| Table 2 Constructs and Cronbach’s Alpha | |||

| Construct | Indicator | Scale used | Cronbach’s alpha |

| Organizational Image | What is your overall impression of the company’s corporate image? | 1 - very bad/poor/negative 7 - very good/excellent/positive | 0.985 |

| Organizational Performance | Please rate the overall performance of the company | 1 - I think the company is performing badly/I have a negative opinion about this company/My opinion is unfavorable 7 - I think the company is performing well/I have a positive opinion about this company/My opinion is favorable | 0.915 |

| Purchasing Intentions | How likely would it be for you to consider the product from this company? | 1 - Very unlikely/not probable/impossible 7 - Very likely/highly probably/possible” | 0.945 |

Data Analysis

The purpose of this study is to examine if the visibility/proximity of the organization to the end consumer affects the influence of CSP on corporate image, financial performance, and consumers’ purchase intentions when an organization faces a scandal. Three hypotheses were stated in order to examine it. Since it was expected that there would be a difference in organizational outcomes between organizations facing a socially irresponsible behavior event (scandal) and those organizations in non-scandal conditions, regardless of the company’s position in the supply chain (visibility/proximity of the organization to the end consumer), a two-way ANOVA and two one-way ANOVAs were performed.

Hypothesis one (H1) stated that consumers’ perspectives on organizational corporate image would be negatively impacted by scandals, regardless of the organization’s position in the supply chain. In order to test H1, a two-way ANOVA was presented with scandals and supply chain members as independent variables and customers’ overall impression of a company’s corporate image as dependent variables. Hypothesis two stated that a consumer’s evaluation of organizational financial performance would be negatively impacted by scandals, regardless of the organization’s position in the supply chain. To test this hypothesis, a one-way ANOVA was performed with scandals as independent variables and consumers’ evaluation of corporate performance as dependent variables. Hypothesis three stated that consumers’ purchase intentions of organizational products would be negatively impacted by scandals regardless of the organization’s position in the supply chain. This hypothesis was tested using a one-way ANOVA in which scandals were the independent variable and purchase intentions the dependent one.

Results

The results of hypothesis one indicate that the overall impression of organizational corporate image is significantly different between participants in scandal condition (M=2.500) and those in non-scandal condition (M=4.930, p<.001). Furthermore, there is no mean difference of overall impression on corporate image between participants in manufacturer’s scandal condition (M=2.414) versus participants in retailer’s scandal condition (M=2.593, p>.05). Therefore, hypothesis one is supported (Tables 3 and 4).

| Table 3 Cell Sizes and Mean Differences Across Conditions for Hypothesis 1 | |||

| Manufacturer | Retailer | Manufacturer vs Retailer | |

| Scandal Condition | |||

| Cell size | 29 | 27 | |

| Mean | 2.069 | 2.531 | p>.05 |

| Standard Deviation | 1.549 | 1.654 | |

| Non-Scandal Condition | |||

| Cell size | 30 | 27 | |

| Mean | 4.911 | 4.778 | p>.05 |

| Standard Deviation | 0.888 | 1.333 | |

| Scandal vs Non-Scandal | p<.001 | p<.001 | |

| Table 4 Cell Sizes and Mean Differences Across Conditions for Hypothesis 2 | |||

| Manufacturer | Retailer | Manufacturer vs Retailer | |

| Scandal Condition | |||

| Cell size | 29 | 27 | |

| Mean | 2.414 | 2.593 | p>.05 |

| Standard Deviation | 1.455 | 1.360 | |

| Non-Scandal Condition | |||

| Cell size | 30 | 27 | |

| Mean | 4.989 | 4.864 | p>.05 |

| Standard Deviation | 0.882 | 0.944 | |

| Scandal vs Non-Scandal | p<.001 | p<.001 | |

For hypothesis two, a similar pattern to the results of H1 was expected. As expected, the analysis showed that participants rated the organizational performance higher when the organization reported normal operations (M=4.848) compared to the organizations that were facing unethical organizational behavior events (M=2.292, p<.001). Please note that the results did not differ between manufacturer’s condition (M=2.069) and retailer’s condition (M=2.531, p>.05) when companies were involved in scandals. Therefore, hypothesis two is supported as well.

For hypothesis three, the same pattern was found; the results indicate that participants’ purchase intentions of products from organizations facing scandal conditions (M=2.548) was significantly lower when compared to purchasing intentions of products from organizations in non-scandal conditions (M=4.737, p<.001). Once again, there was no difference of consumers’ purchase intentions between participants in manufacturer’s scandal condition (M=2.563) versus participants in retailer’s scandal condition (M=2.531, p>.05). Therefore hypothesis three is also supported (Table 5).

| Table 5 Cell Sizes and Mean Differences Across Conditions for Hypothesis 3 | |||

| Manufacturer | Retailer | Manufacturer vs Retailer | |

| Scandal Condition | |||

| Cell size | 29 | 27 | |

| Mean | 2.563 | 2.531 | p>.05 |

| Standard Deviation | 1.561 | 1.445 | |

| Non-Scandal Condition | |||

| Cell size | 30 | 27 | |

| Mean | 4.711 | 4.765 | p>.05 |

| Standard Deviation | 1.237 | 1.304 | |

| Scandal vs Non Scandal | p<.001 | p<.001 | |

Discussion and Conclusion

The objective of the study was to demonstrate that a negative organizational event (scandal) would have the same effect on the organizational outcomes (financial performance, organizational image, and consumers’ purchase intentions) of a manufacturer, when compared to the effect on a retailer’s organizational outcomes. In other words, any organization facing scandalous conditions will have the same potential loss in organizational image, financial performance, and consumers’ purchasing intentions, regardless of the organization’s position in the supply chain (visibility/proximity of the organization to the end consumer). With the intention to achieve this objective, three hypotheses were stated and tested using a sample size of 113 subjects; intriguingly, all the hypotheses were supported.

Even though previous research shows that supply chain members closer to the final consumer have more visibility, and hence their signaling capability appears to be stronger, spillover effects seem to neutralize this visibility and communication capability since being part of an integrated supply chain leaves no room for innocent parties. Thus, the results found here support the idea that scandals have a negative effect on organizational outcomes (financial performance, organizational image, and consumers’ purchase intentions), regardless of the organization’s position in the supply chain.

Contribution and Implication

While previous studies mainly focus on socially responsible behavior and its relationship to performance, this study aimed to go further by taking a view on the negative side of this scenario (unethical or socially irresponsible behaviors/scandal) and how it affects not only the organizational financial performance but also the organizational image, and even more importantly, the consumers’ purchasing intentions. Consumers’ responses to socially irresponsible practices are generally noticeable; sales drops are quite common after scandal revelations. It is important to emphasize the practical implications of this study. The outcome suggests that organizations should pay more attention to CSP efforts and actively engage in corporate social reporting to the public since signaling theory suggests that this positive message to the market would improve the organization’s future potential. Even though CSP reporting may involve costly efforts, and many organizations may strategically reveal information to maximize financial benefits under social pressure to avoid additional disclosure costs, it is important to emphasize that CSP efforts and CSP broadcasting have a positive impact on the organizational financial performance, the corporate image, and most importantly, the customers’ purchasing intentions. Thus, it is of vital importance for organizations to engage in positive CSP activities since this will improve the probability of survival in the market, especially in unstable environments.

Limitation and Future Research

Future research is needed to eliminate the limitations of this research. Future studies may be aimed at examining the effects of specific types of socially irresponsible corporate behavior (scandals). Scandalous conditions and the effects of interaction with supply chain member relationships should also be studied.

Additional studies could compare the effects of organizational unethical behaviors in integrated supply networks versus traditional distribution channels and analyze the financial and social influences of spillover effect of upstream members to downstream members.

References

- Alon, A., & Vidovic, M. (2015). Sustainability performance and assurance: Influence on reputation. Corporate Reputation Review, 18(4), 337-352.

- Arikan, E., Kantur, D., Maden, C., & Telci, E. E. (2016). Investigating the mediating role of corporate reputation on the relationship between corporate social responsibility and multiple stakeholder outcomes. Quality & Quantity, 50(1), 129-149.

- Ayers, J.B. & Odegaard, M.A. (2008). Retail Supply Chain Management, Auerbach Publications. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis Group

- Brown, B. (1998). Do stock market investors reward companies with reputations for social performance?. Corporate Reputation Review, 1(3), 271-280.

- Campbell, C. (2001). Social capital and health: contextualising health promotion within local community networks.

- Carroll, A. B. (1979). A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Academy of Management Review, 4(4), 497-505.

- Donaldson, T., & Preston, L. E. (1995). The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. Academy of Management Review, 20(1), 65-91.

- Fearon, J. D. (1997). Signaling foreign policy interests: Tying hands versus sinking costs. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 41(1), 68-90.

- Forrester, J. (1961). Industrial Dynamics. Waltham. MA: Pegasus Communications.

- Graves, S. & Waddock, S. (1994). Institutional owners and corporate social performance. Academy of Management Journal, 37(4), 1034-46.

- Greening, D. W., & Turban, D. B. (2000). Corporate social performance as a competitive advantage in attracting a quality workforce. Business & Society, 39(3), 254-280.

- Hay, R. D., Gray, E. R., & Gates, J. E. (Eds.). (1976). Business & Society: Cases and text. South Western Publishing Company.

- Koslow, S. (2000). Can the truth hurt? How honest and persuasive advertising can unintentionally lead to increased consumer skepticism. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 34(2), 245-267.

- Krebs, J. R. (1984). Animal signals: mindreading and manipulation. Behavioural Ecology: An Evolutionary Approach, 380-402.

- McWilliams, A., & Siegel, D. (2001). Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Academy of Management Review, 26(1), 117-127.

- Moskowitz, M. (1972). Choosing socially responsible stocks. Business and Society Review, 1(1), 71-75.

- Mohr, L. A., & Webb, D. J. (2005). The effects of corporate social responsibility and price on consumer responses. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 39(1), 121-147.

- Mohr, L. A., Webb, D. J., & Harris, K. E. (2001). Do consumers expect companies to be socially responsible? The impact of corporate social responsibility on buying behavior. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 35(1), 45-72.

- Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2006). The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harvard Business Review, 84(12), 78-92.

- Ruekert, R. W., & Rao, A. (1994). Brand alliances as signals of product quality. Sloan Management Review, 36(1), 87-97.

- Roehm, M. L., & Tybout, A. M. (2006). When will a brand scandal spill over, and how should competitors respond?. Journal of Marketing Research, 43(3), 366-373.

- Robson, P. (1998). The economics of International Integration. Routledge: London.

- Sen, S., & Bhattacharya, C. B. (2001). Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(2), 225-243.

- Smith, J. M., & Harper, D. (2003). Animal signals. Oxford University Press.

- Spence, M. (1973). VJob market signalingV. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87(3), 355.

- Su, W., Peng, M. W., Tan, W., & Cheung, Y. L. (2016). The signaling effect of corporate social responsibility in emerging economies. Journal of Business Ethics, 134(3), 479-491.

- Ullman, A. A. (1985). Data in search of a theory: A critical examination of the relationships among social performance, social disclosure, and economic performance of US firms. Academy of Management Review, 10(3), 540-557.

- Wood, D. J. (1991). Corporate social performance revisited. Academy of management review, 16(4), 691-718.

- Wood, D. (2016). Corporate social performance. Oxford Bibliographies. Retrieved July 27, 2016, from http://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199846740/obo-9780199846740-0099.xml.

- Guo, Z. Y., & Luo, Y. (2017). Credit constraint exports in countries with different degrees of contract enforcement. Business and Economic Research, 7(1), 227-241.

- Zeithaml, V. A., Berry, L. L., & Parasuraman, A. (1993). The nature and determinants of customer expectations of service. Journal of the academy of Marketing Science, 21(1), 1-12.