Case Studies: 2025 Vol: 26 Issue: 6

THE GREAT GLOBAL UNCERTAINTY: THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC AS A CASE STUDY

Mauro Visaggio, University of Perugia

Citation Information: Visaggio, M. (2025). The Great Global Uncertainty: The Covid-19 Pandemic as a Case Study. Journal of Economics and Economic Education Research, 2025, 26(S6) 1-12.

Abstract

This paper analyzes the COVID-19 pandemic as a case study within the broader phase of the Great Global Uncertainty. The objective is threefold. First, the paper reconstructs the economic evolution of the pandemic between 2020 and 2022, highlighting the sequence of shocks that characterized both the recessionary phase and the subsequent recovery. Second, it examines the macroeconomic policy responses adopted to address the health emergency and its economic consequences, with particular attention to the interaction between ultra-expansive fiscal policy and unconventional monetary policy. Third, the paper applies a simple macroeconomic framework to interpret the crisis, showing how the pandemic can be understood as a combined supply- and demand-side shock amplified by policy interventions. By treating COVID-19 as a case study, the paper provides a theoretical interpretation of the economic dynamics observed during the initial phase of the Great Global Uncertainty.

Keywords

Great Global Uncertainty, COVID-19 pandemic, macroeconomic policy

Introduction

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization officially declared COVID-19 a global pandemic. At that time, world economies appeared to have largely overcome the lingering effects of the 2007–2008 financial crisis and to be firmly placed on a path of stable growth. Unlike previous major economic crises, the pandemic represented a grey/black swan originating outside the economic system, arising instead from the health sphere, in a manner comparable to the Spanish flu pandemic that spread during the final phase of the First World War.

The COVID-19 pandemic marked the beginning of a broader historical phase characterized by an unusually high degree of uncertainty. This phase has increasingly been described as one of persistent or systemic uncertainty, in which large and heterogeneous shocks follow one another in rapid succession, generating unstable expectations and amplifying macroeconomic volatility.

The diffusion of the neologism permacrisis, selected by the Collins Dictionary as the Word of the Year in 2022 and defined as “an extended period of instability and insecurity, especially one resulting from a series of catastrophic events,” reflects the growing perception of this structural condition of instability.

A similar interpretation is explicitly adopted by Christine Lagarde, President of the European Central Bank, who in her 2022 Frankfurt speech “Macroprudential policy in Europe: building resilience in a challenging environment” observed that future historians may well describe the current period as an era of permacrisis, shaped by the rapid succession of powerful shocks such as the pandemic, geopolitical conflicts, and the energy crisis.

Recent contributions emphasize how the COVID-19 shock triggered an unprecedented surge in economic uncertainty, comparable in magnitude only to major historical crises (Bloom, 2009; Baker et al., 2020). Within this broader framework, the present paper focuses exclusively on the COVID-19 pandemic as a case study of the Great Global Uncertainty.

The objective is to analyze its economic dynamics and macroeconomic implications. In line with recent analyses, the pandemic is interpreted as a compound shock simultaneously affecting aggregate demand and aggregate supply, and interacting with large-scale policy interventions (Gourinchas, 2020).

Specifically, the paper reconstructs the economic evolution of the pandemic, distinguishing between the recessionary phase and the subsequent recovery. It then examines the macroeconomic policy responses adopted to address the crisis, with particular attention to fiscal expansion and unconventional monetary policy. Finally, the paper applies a simple macroeconomic framework to interpret the pandemic shock and the associated policy responses, highlighting the role of central banks in stabilizing financial conditions during periods of extreme uncertainty (Forbes and Gagnon, 2021).

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 1 focuses on the first phase of the pandemic. Section 2 examines the second phase. Section 3 presents the macroeconomic interpretation of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The First Phase of the Covid-19 Pandemic: The Global Recession

The spread of the pandemic can be divided into two distinct phases, separated by the discovery of the vaccine and the start of mass vaccination in the first months of 2021, which broadly correspond to a recessionary phase and a subsequent economic recovery. After briefly outlining the initial stages of the pandemic at the global level, this section examines the health and economic policy measures adopted to address the crisis during both the pre-vaccine and post- vaccine phases.

Spread of the Pandemic

In December 2019, a pneumonia of unknown etiology emerged in Wuhan, a city in China’s Hubei province. Initially, the outbreak did not raise major concern, as transmission was believed to occur only from animals to humans. This assessment changed rapidly in mid-January, when human-to- human transmission was confirmed. In response, the World Health Organization declared a public health emergency of international concern and officially identified the disease as Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. The virus spread at an extraordinary pace, reaching a global scale within little more than one month and leading the World Health Organization to declare a pandemic on March 11, 2020. The global health emergency formally ended only in May 2023, after approximately three years.

The evolution of the pandemic unfolded through successive epidemic waves. Although the concept of an epidemic wave does not admit a perfectly precise definition, it can be described as a cyclical pattern in which periods of rising infections, starting from a local minimum and culminating in a peak, are followed by phases of declining cases that eventually reach a new minimum. A wave is considered exhausted when infections fall to low and relatively stable levels, while a new wave begins when a sustained increase in cases is observed.

From an economic perspective, the development of the pandemic can be broadly divided into two distinct phases, separated by the introduction of mass vaccination campaigns at the end of 2020 and in the early months of 2021. Despite some lag, this distinction closely mirrors the two main phases of the economic cycle observed during the pandemic: an initial recessionary phase followed by a recovery phase.

During the pre-vaccine period, which extends from early 2020 to the end of that year, governments worldwide were confronted with a severe trade-off between protecting public health and sustaining economic activity. In the absence of an effective vaccine, health containment relied primarily on lockdown measures of varying intensity, which significantly restricted mobility and productive activity. At the same time, governments adopted ultra-expansive macroeconomic policies in an attempt to mitigate the depth of the ensuing recession.

In the post-vaccine period, health containment strategies progressively shifted toward vaccination incentives and targeted measures aimed at limiting virus transmission without resorting to generalized lockdowns. In parallel, macroeconomic policies increasingly focused on consolidating economic recovery.

Public Health Emergency and Generalized Lockdown

In the first phase of the pandemic, governments were required to make decisions under the pressure of two conflicting emergencies. On the one hand, the rapid spread of the virus and the sharp increase in mortality, in the absence of an effective vaccine, made strict social distancing unavoidable in order to limit the number of deaths. On the other hand, an economic emergency emerged as a direct consequence of mobility restrictions, which implied a severe contraction of productive activity.

The severity of the health emergency during the initial phase of the pandemic was reflected in the rapid surge of infections and deaths observed over a very short period of time. New cases increased sharply, reaching a peak within a few weeks, while deaths followed with a slight delay. Despite the relatively limited number of detected infections in the early stages, mortality was proportionally high, indicating both the extreme vulnerability of health systems and their limited capacity to contain the spread of the disease. In this phase, the ratio between deaths and newly detected cases reached exceptionally elevated levels, signaling the acute severity of the health shock.

Health containment measures adopted during successive epidemic waves shared a common feature: the need to strike a balance between two inherently conflicting objectives. The first was

the protection of public health, while the second was the preservation of economic activity in order to prevent a collapse in production. Maintaining high levels of economic activity would have inevitably entailed higher human costs, whereas prioritizing health protection required severe restrictions on mobility and production.

Across countries, health policies implemented during the first phase of the pandemic ranged between two extreme approaches. At one extreme, some governments adopted highly restrictive strategies based on generalized lockdowns, severely limiting individual mobility and suspending most non-essential economic activities. At the opposite extreme, other governments pursued more permissive strategies, allowing a broader circulation of the virus among the population while keeping restrictions on movement and production relatively limited.

In practice, health containment strategies evolved over time in response to changes in epidemiological conditions. Periods of strict lockdown were followed by phases of gradual relaxation as infections and deaths declined, allowing for temporary returns toward normal economic activity. As the prospect of an effective vaccine became increasingly concrete, containment measures were managed with greater flexibility, relying on differentiated restrictions calibrated to the intensity of virus transmission.

Economic Recession and Ultra-expansive Macroeconomic Policies

The pandemic crisis revived in the Eurozone the long-standing issue of coordination between fiscal and monetary policy that had already emerged during the 2007–2008 financial crisis. In the United States, monetary policy conducted by the Federal Reserve is supported by a centralized fiscal authority responsible for fiscal policy at the federal level. This institutional arrangement allows, within certain limits, for relatively effective coordination between the two macroeconomic policies.

By contrast, in the Eurozone—a recently established optimal currency area—monetary policy is centralized and managed by the European Central Bank, while fiscal policy remains decentralized and is conducted at the national level within a framework of fiscal rules defined by European treaties, such as the Stability and Growth Pact. As a result, policy coordination, particularly during recessionary phases, is inherently more complex.

In the economic crisis triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic, however, macroeconomic policy responses in the Eurozone differed markedly from those adopted during the 2007–2008 financial crisis. Unlike the earlier episode, the policy mix implemented during the pandemic did not substantially diverge from that adopted in the United States, either in terms of timing or intensity. During the global financial crisis, the emphasis on expansionary austerity and the delayed adoption of unconventional monetary policies contributed to a prolonged and uneven recovery, especially in highly indebted economies. By contrast, during the pandemic, both fiscal and monetary policies were deployed rapidly and on an unprecedented scale, reflecting a significant shift in the macroeconomic policy framework.

Quantitative easing monetary policies of the ECB and the Fed

Throughout the pandemic period, and in particular until the third quarter of 2021—when inflationary pressures remained subdued—the monetary policy stance of the European Central Bank was decisively and promptly expansionary. At the outbreak of the pandemic, the Eurozone was already characterized by a prolonged environment of very low interest rates and inflation close to zero, a configuration consistent with a liquidity trap. In this context, conventional monetary policy instruments had limited effectiveness, leading the ECB to rely extensively on unconventional measures centered on large-scale asset purchases and targeted liquidity provision. Within this framework, the ECB pursued three closely related objectives. First, it aimed to preserve access to credit for households and firms during a phase of severe disruption in economic activity. Second, it sought to safeguard financial stability by preventing liquidity shortages and dysfunctions in financial markets. Third, it aimed to ensure the sustainability of sovereign debt by containing borrowing costs at a time when public deficits were expanding sharply in response to the crisis. Monetary interventions were concentrated mainly in the initial months of the pandemic, reflecting the urgency of stabilizing financial conditions. Policy rates were maintained at levels close to zero, reinforcing an accommodative stance that had been in place since the mid-2010s. At the same time, existing asset purchase programs were reactivated and expanded, while new instruments were introduced to strengthen liquidity provision to the banking system. Refinancing operations were enhanced in both scale and maturity, allowing credit institutions to obtain long-term funding under highly favorable conditions, conditional on the maintenance of lending to the real economy. The pandemic crisis revived in the Eurozone the long-standing issue of coordination between fiscal and monetary policy that had already emerged during the 2007–2008 financial crisis. In the United States, monetary policy conducted by the Federal Reserve is supported by a centralized fiscal authority responsible for fiscal policy at the federal level, an institutional arrangement that allows, within certain limits, for relatively effective coordination between the two macroeconomic policies. By contrast, in the Eurozone—a recently established optimal currency area—monetary policy is centralized and managed by the European Central Bank, while fiscal policy remains decentralized and is conducted at the national level within a framework of fiscal rules defined by European treaties, such as the Stability and Growth Pact. As a result, policy coordination, particularly during recessionary phases, is inherently more complex.

In the economic crisis triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic, however, macroeconomic policy responses in the Eurozone differed markedly from those adopted during the 2007–2008 financial crisis. Unlike the earlier episode, the policy mix implemented during the pandemic did not substantially diverge from that adopted in the United States, either in terms of timing or intensity. During the global financial crisis, the emphasis on expansionary austerity and the delayed adoption of unconventional monetary policies contributed to a prolonged and uneven recovery, especially in highly indebted economies. By contrast, during the pandemic, both fiscal and monetary policies were deployed rapidly and on an unprecedented scale, reflecting a significant shift in the macroeconomic policy framework.

A central element of the ECB’s response was the introduction of a pandemic-specific asset purchase program designed to operate with a high degree of flexibility across time, asset classes, and

jurisdictions. By purchasing large quantities of public securities on secondary markets, the ECB aimed to prevent fragmentation in sovereign bond markets and to facilitate the financing of the substantial fiscal expansions implemented to support economic recovery. The scale and speed of these interventions marked a significant intensification of the unconventional monetary policy framework developed in previous years.

The monetary policy response of the Federal Reserve closely mirrored that of the ECB in terms of timing, scale, and scope. After a period of gradual monetary tightening that began in the mid-2010s, the Federal Reserve rapidly reversed course as the economic consequences of the pandemic became apparent. In March 2020, the policy rate was cut sharply to near-zero levels, effectively placing the U.S. economy in a liquidity trap similar to that observed in the Eurozone. In parallel with the reduction in policy rates, large-scale asset purchases were resumed and substantially expanded. Following a phase of balance sheet normalization, the Federal Reserve reintroduced quantitative easing on an unprecedented scale, initially through massive purchases of public securities and mortgage-backed securities, and subsequently through a sustained expansion of its balance sheet. Although the pace of purchases moderated after the initial shock, the accommodative stance was maintained throughout 2020 and into early 2021.

Beyond traditional asset purchases, the Federal Reserve deployed a broad set of facilities aimed at stabilizing financial markets and supporting credit flows across a wide range of economic sectors. These interventions included short-term liquidity provision to financial institutions, support for key funding markets, direct purchases of corporate debt instruments, and credit facilities targeting firms, financial intermediaries, and subnational entities. The breadth of instruments reflected an explicit intention to prevent the health shock from evolving into a systemic financial crisis.

A defining feature of the Federal Reserve’s response was the exceptional speed with which these measures were announced and implemented. Most interventions were introduced within a narrow time window during the early weeks of the pandemic, underscoring the central role of monetary policy in containing financial instability and supporting economic activity during the acute phase of the crisis.

Ultra-Expansive Fiscal Policies in the Eurozone and the United States

The institutional context in which fiscal policy was conducted during the COVID-19 crisis differed markedly from that prevailing in the aftermath of the 2007–2008 financial crisis. In that earlier episode, fiscal policy in the Eurozone was largely guided by the principle of so-called expansionary austerity, which imposed strict constraints on the use of deficit-financed stimulus measures. The underlying assumption was that fiscal consolidation, rather than expansion, would restore confidence and foster economic growth in countries characterized by high public debt. Subsequent experience— particularly in economies with severe fiscal imbalances—suggests that this strategy resulted in a prolonged and sluggish recovery, casting serious doubt on the effectiveness of austerity-based prescriptions in deep recessionary contexts.

By contrast, the pandemic crisis prompted a decisive shift in the European fiscal policy framework. Faced with an unprecedented shock threatening not only economic activity but also social and political stability, the application of existing fiscal rules was effectively suspended. Both the Stability and Growth Pact and the Fiscal Compact were set aside, allowing national governments to deploy large-scale discretionary fiscal measures. At the European level, this shift was accompanied by the introduction of common fiscal instruments aimed at providing immediate support to labor markets and financing medium- and long-term recovery efforts. Taken together, these measures represented a significant step toward a more coordinated fiscal response within the Eurozone.

At the national level, fiscal expansion took the form of a broad set of emergency interventions designed to cushion the impact of lockdown measures on households and firms. Policy actions focused on three main objectives: direct income support, the postponement of tax and social security obligations,

and the provision of public guarantees and credit facilities to sustain business liquidity. The scale of the resources mobilized in the initial months of the pandemic was unprecedented in peacetime, reflecting both the severity of the economic disruption and the determination of governments to prevent a permanent loss of productive capacity.

A similarly expansive approach characterized fiscal policy in the United States. Between the spring of 2020 and early 2021, successive fiscal packages were approved, resulting in a massive injection of public resources into the economy. These measures included direct transfers to households, support for businesses, assistance to state and local governments, and increased funding for healthcare and research. Both the magnitude and the speed of implementation of these interventions were exceptional, contributing to a rapid stabilization of income and aggregate demand during the most acute phase of the crisis.

Overall, the first phase of the pandemic was defined by two closely interconnected features. On the one hand, the absence of an effective vaccine necessitated widespread lockdown measures, leading to a sudden and severe contraction of economic activity. On the other hand, governments and central banks responded with fiscal and monetary interventions of unprecedented magnitude and speed, aimed at offsetting the collapse in private demand and preserving the productive structure of their economies.

The Second Phase of the Covid-19 Pandemic: Vaccination, Reopening, and Economic Recovery

The turning point in the evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic, and simultaneously in the economic cycle over the 2020–2022 biennium, is represented by the discovery and subsequent commercialization of effective vaccines and by the launch of large-scale vaccination campaigns. The rapid expansion of vaccine coverage—eventually exceeding 80 percent of the population in many countries—made it possible to achieve a form of herd immunity sufficient to allow economic systems to resume activity on a broad scale.

Between early 2021 and the formal end of the state of emergency in March 2022, additional pandemic waves occurred. Unlike the initial phase, however, these waves did not generate comparable disruptions to economic activity. As early as the second half of 2020, growing confidence in the imminent availability of vaccines led to a marked shift in health policy strategies. The scope and intensity of lockdown measures were progressively reduced, while reopening processes became increasingly widespread.

This change in policy stance became more pronounced with the start of vaccination campaigns in early 2021. Throughout that year, containment of the pandemic relied primarily on measures designed to promote vaccination, including the introduction of health certification systems linked either to vaccination or recovery from infection. Over time, such certifications became mandatory for access to a wide range of public spaces and workplaces, effectively replacing generalized lockdowns as the main instrument of health policy.

The evolution of epidemiological indicators over this period highlights the decisive role played by vaccination in mitigating the most severe effects of the pandemic. As vaccine coverage expanded and reached high levels, the fatality rate declined sharply and stabilized at very low values, despite the persistence of new infection waves. This decoupling between contagion dynamics and severe health outcomes made it possible to progressively normalize economic activity and ultimately led to the termination of the state of emergency in early 2022.

Macroeconomic Policies of Consolidation between Economic Recovery and Inflation

In the second phase of the pandemic, the progressive relaxation of lockdown measures— made possible by the vaccination campaign and the gradual achievement of herd immunity— allowed for the almost complete reopening of productive activities. At the same time, macroeconomic policies initially accompanied the recovery of economic activity through consolidation measures, at least until the rapid

expansion of aggregate demand generated an unexpected feedback effect: a sustained and generalized increase in inflation.

During the recovery phase, the monetary policy stance of both the European Central Bank and the Federal Reserve underwent a gradual but decisive reversal. After an extended period of strong expansionary interventions, monetary policy shifted toward a restrictive orientation, passing through an intermediate phase of tapering.

As discussed earlier, the response of governments and central banks to the deep recession triggered by the pandemic was exceptional in both scale and speed. Ultra-accommodative monetary policy and large fiscal deficits, combined with the rollout of vaccines, played a central role in sustaining aggregate demand and fostering a rapid recovery already by the end of 2020. However, the strength of the rebound produced an adverse macroeconomic side effect: inflation rose to levels not observed for several decades, recalling dynamics that were last experienced in the second half of the 1970s.

The sharp increase in aggregate demand, driven by expansive fiscal policy and by the massive liquidity injected into the economy by central banks—was not matched by an equally rapid adjustment on the supply side. As a result, upward pressure on prices intensified, giving rise to a classic episode of demand-pull inflation. Central banks thus found themselves once again confronted with the traditional trade-off between inflation and economic activity, facing the dilemma of whether to tighten monetary policy at the risk of slowing the recovery or to maintain an accommodative stance and tolerate higher inflation in the expectation that it would prove temporary.

Throughout much of 2021, both the ECB and the Fed adopted a cautious approach. Subsequently, starting in the second half of the year, they initiated a gradual normalization of monetary policy through a three-stage process. First, asset purchases under quantitative easing programs were progressively reduced through tapering. Second, policy interest rates were increased after a prolonged period at the effective lower bound. Third, balance sheet reduction was implemented through the active or passive unwinding of previously accumulated assets.

In the United States, the Federal Reserve began tapering its asset purchases in late 2021, gradually reducing the pace of Treasury and mortgage-backed securities acquisitions. This was followed, in early 2022, by the first increase in the policy rate since the onset of the pandemic, initiating a tightening cycle that brought interest rates to restrictive levels by mid-2023. At the same time, the Federal Reserve began reducing the size of its balance sheet, marking the transition to quantitative tightening.

In the Eurozone, a similar sequence unfolded with a slight delay. Asset purchases were progressively scaled back during 2021, and policy rates increased starting in mid-2022 after several years at zero or negative levels. Subsequently, the ECB initiated balance sheet normalization by reducing its holdings of assets accumulated under its purchase programs.

Overall, between late 2021 and the first half of 2022, monetary policy in both the United States and the Eurozone completed the transition from peak quantitative easing to a regime characterized by tapering, rising policy rates, and ultimately quantitative tightening.

During the second phase of the pandemic, fiscal policy largely followed the trajectory established in the initial phase, consolidating the support measures already in place. In the United States, additional fiscal packages approved at the end of 2020 and in early 2021 extended income support, unemployment benefits, and transfers to state and local governments. In Europe, national fiscal policies continued to provide targeted support to households and firms affected by the lingering effects of the health crisis, building upon the emergency measures introduced in 2020.

In sum, the second phase of the COVID-19 pandemic was characterized by a clear asymmetry in macroeconomic policy adjustments. On the health policy side, generalized lockdowns were almost entirely abandoned in favor of vaccination-based containment strategies. On the macroeconomic policy side, fiscal policy maintained a broadly supportive stance, while monetary policy underwent a gradual

but irreversible shift from ultra-expansionary measures toward monetary tightening, passing through an intermediate phase of tapering.

Pandemic Economic Cycle: An Overview

This section provides an overview of the economic cycle that began in the early months of 2020 and unfolded during the global spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. The recession triggered by the pandemic was exceptionally short-lived. In the United States, economic activity reached a peak at the beginning of 2020 and a trough only a few months later, marking the end of the recessionary phase and the rapid transition to recovery. Similar dynamics characterized other advanced economies.

Beyond its extreme brevity, the pandemic-induced recession displays a second distinctive feature: the extraordinary speed of the subsequent recovery. After the sharp contraction recorded in the first half of 2020, real output returned to pre-crisis levels within a remarkably short time span. Compared with previous major downturns—most notably the global financial crisis—the recovery following the COVID-19 shock was unprecedented in both timing and intensity. This pattern gives rise to a clearly identifiable V-shaped economic cycle.

The pandemic economic cycle can therefore be divided into two main phases: an initial recessionary phase, characterized by generalized lockdowns and ultra-expansive macroeconomic policies, and a recovery phase, driven by vaccination, policy support, and a rapid rebound in aggregate demand.

Recessionary Phase: Generalized Lockdowns and Ultra-Expansive Policies

The recessionary phase, concentrated in the first part of 2020, is characterized by two main features. First, the contraction in economic activity was extremely abrupt, reflecting the sudden and widespread suspension of productive activities following the introduction of health containment measures. Second, output volatility was exceptionally high, with a large gap between the peak and the trough of economic activity over a very short period.

The collapse in production was reflected in labor market dynamics and price developments. While the closure of productive activities led to job losses, the increase in measured unemployment remained relatively contained in several countries. This outcome was largely driven by job retention schemes, temporary freezes on layoffs, and the sharp decline in job search activity during lockdowns.

Inflation dynamics during the recessionary phase were shaped by two opposing forces. On the supply side, restrictions on production exerted upward pressure on prices. On the demand side, the collapse in income, consumption, and international trade generated strong downward pressure. The demand-side effect dominated, leading to a generalized decline in inflation rates, which in many economies approached zero. In a context of near-zero nominal interest rates, this implied extremely low real interest rates and reinforced liquidity trap conditions.

Overall, the recessionary phase of the pandemic economic cycle was triggered by the joint occurrence of a negative supply shock—stemming from lockdowns and production constraints— and a dominant negative demand shock, resulting from the contraction of consumption, investment, and exports. The prevalence of the demand-side contraction explains why the sharp decline in output was accompanied by falling inflation.

Recovery Phase: Vaccination and Policy-Driven Rebound

The recovery phase began shortly after the trough in economic activity and was initially rapid and sustained. Economic growth rebounded strongly as health restrictions were progressively lifted and vaccination campaigns expanded. This phase continued until early 2022, when new geopolitical shocks contributed to a slowdown in global economic momentum.

The recovery was accompanied by a gradual normalization of labor markets and a pronounced acceleration in inflation. Inflation rates rose sharply across advanced economies, reaching levels not

observed for several decades. In the presence of persistently accommodative monetary conditions, this surge in inflation translated into negative real interest rates, further stimulating aggregate demand.

The V-shaped recovery reflects the combined action of three mutually reinforcing factors. First, the abandonment of generalized lockdowns and the shift toward vaccination-based health strategies allowed productive capacity to be restored. Second, ultra-expansive fiscal policies sustained household income and aggregate demand. Third, unconventional monetary policies— centered on large-scale asset purchases and near-zero policy rates—accommodated fiscal expansion and prevented financial instability.

While this policy mix proved highly effective in restoring output, it also generated two significant side effects: a sharp rise in inflation and a substantial increase in public debt.

Inflationary Pressures and Public Debt Dynamics

The surge in inflation during the recovery phase can be attributed to two main mechanisms. The first is the presence of supply bottlenecks. The rapid rebound in demand encountered rigidities in production capacity and global supply chains, particularly in sectors characterized by complex input structures. These constraints led to price pressures consistent with demand-pull inflation dynamics, especially in goods-producing sectors excluding food and energy.

The second mechanism relates to inflation expectations. As inflation accelerated, expectations of further price increases became increasingly entrenched, prompting firms with market power to adjust prices upward in anticipation of higher future costs.

At the same time, the recovery phase was associated with a marked increase in public debt. Large fiscal deficits implemented to support households, firms, and employment translated into higher debt-to-GDP ratios across advanced economies. Although accommodative monetary policy mitigated the immediate financing burden, the legacy of the pandemic includes significantly higher public debt levels relative to the pre-crisis period.

Macroeconomic Interpretation of the Covid-19 Pandemic

At this point, a simple macroeconomic framework can be used to provide a theoretical interpretation of the dynamics observed during the COVID-19 pandemic. In particular, the two phases of the pandemic economic cycle are analyzed separately: the recessionary phase and the subsequent recovery phase.

Recessionary Phase

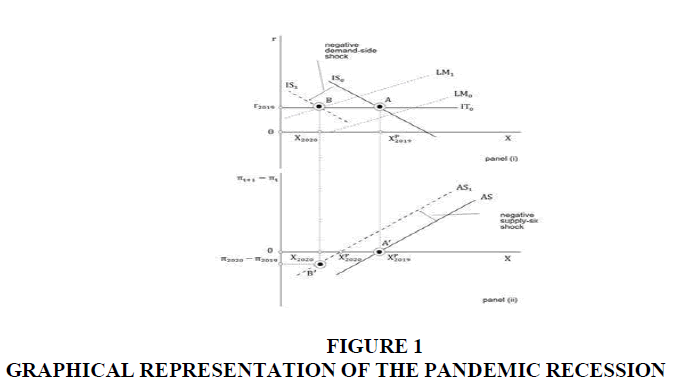

Figure 1 provides a graphical representation of the recessionary phase of the pandemic economic cycle. Panel (i) depicts equilibrium in the goods and money markets, represented by the IS curve, the monetary policy rule (IT curve), and the LM curve. Panel (ii) illustrates equilibrium in the labor market through the aggregate supply (AS) curve.

At the end of 2019, the economy is assumed to be in an initial macroeconomic equilibrium, represented by point A in panel (i) and point A′ in panel (ii). This equilibrium is characterized by output at its full-employment level, a stable inflation rate, and a real interest rate close to zero, consistent with a liquidity trap environment.

The spread of the pandemic generates two simultaneous negative shocks. On the supply side, the health containment measures introduced to limit contagion constitute a negative supply shock.

Which shifts the AS curve leftward in panel (ii), reducing potential output. On the demand side, the collapse in consumption, investment, and exports generates a negative demand shock, represented by a leftward shift of the IS curve in panel (i).

When negative supply and demand shocks occur simultaneously, macroeconomic theory predicts that if the demand shock dominates, actual output falls below the new potential level. As a result, a negative output gap emerges and inflation declines. Graphically, the economy moves from point A to point B in panel (i), while in panel (ii) it moves from point A′ to point B′, where the change in inflation is negative.

Economic Recovery Phase

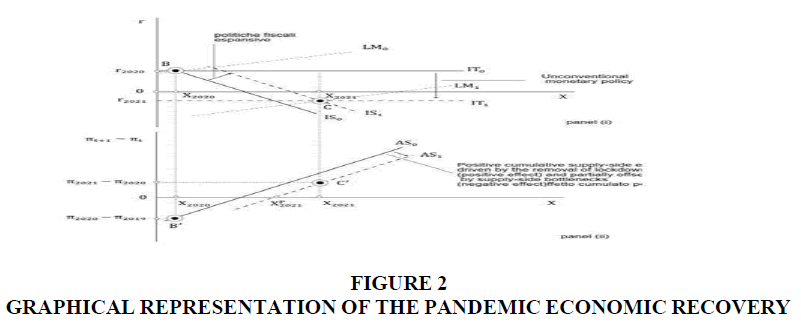

Figure 2 illustrates the recovery phase of the pandemic economic cycle, assuming that the effects of macroeconomic policies interact with the progressive relaxation and eventual abandonment of lockdown measures.

On the supply side, two opposing forces are at work. The easing and subsequent removal of lockdown restrictions constitute a positive supply shock, partially offsetting the initial contraction in productive capacity. At the same time, bottlenecks in production and disruptions in supply chains limit the speed at which supply can adjust to the rapid recovery in demand, generating a countervailing negative supply shock. Assuming that the positive effect dominates, the AS curve shifts rightward, though not fully back to its pre-pandemic position.

On the demand side, the combination of ultra-expansive fiscal policy and unconventional monetary policy, particularly quantitative easing, leads to a strong increase in aggregate demand. In panel (i), this is represented by a rightward shift of the IS curve and a downward shift of the IT curve, reflecting the decline in the real interest rate, which becomes negative during this phase.

Since actual output exceeds the new level of potential output, inflationary pressures emerge. Consequently, the economy moves to point C in panel (i) and to point C′ in panel (ii), where the change in inflation is positive.

Conclusion

This paper has analyzed the COVID-19 pandemic as a case study of the Great Global Uncertainty, interpreting it as the initial and defining episode of a broader historical phase characterized by heightened and persistent macroeconomic instability. By focusing on the period 2020–2022, the analysis has shown that the pandemic generated an unprecedented economic cycle, marked by an extremely short but severe recession followed by a rapid V-shaped recovery. This pattern sharply contrasts with previous major crises and reflects both the exogenous nature of the shock and the exceptional scale of policy interventions.

From a policy perspective, the paper highlights how the pandemic triggered a fundamental shift in the macroeconomic policy framework. Ultra-expansive fiscal policies and unconventional monetary interventions were deployed simultaneously and on an unprecedented scale, allowing governments and central banks to stabilize aggregate demand and to support a rapid recovery once health restrictions were progressively lifted. At the same time, these policies produced important side effects, most notably a sharp increase in inflation and a significant rise in public debt, which have become central features of the subsequent phase of global uncertainty.

The macroeconomic framework adopted in the paper provides a coherent interpretation of these dynamics. The recessionary phase is explained by the joint occurrence of negative supply and demand shocks, with the latter prevailing and generating disinflationary pressures. The recovery phase, by contrast, reflects the combined effects of the removal of lockdown measures and strongly expansionary macroeconomic policies, giving rise to demand-driven inflationary dynamics in a context of constrained supply.

Overall, the COVID-19 pandemic emerges as a paradigmatic manifestation of Great Global Uncertainty, in which large exogenous shocks, policy responses, and macroeconomic feedback effects interact in shaping economic outcomes. As such, the pandemic offers a useful analytical benchmark for understanding how modern economies respond to extreme uncertainty and for assessing the effectiveness and long-term consequences of large-scale macroeconomic stabilization policies in an increasingly unstable global environment.

References

Baker, S. R., Bloom, N., Davis, S. J., & Terry, S. J. (2020). Covid-induced economic uncertainty (No. w26983). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bloom, N. (2009). The impact of uncertainty shocks. Econometrica, 77(3), 623-685.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Dictionary, C. (2022). Permacrisis: Word of the year. Collins—The Collins Word of the Year.

Forbes, K., & Gagnon, J. (2021). A New Era for Central Banking. MIT Sloan Management Review 62 (3).

Gourinchas, P. O. (2020). Flattening the pandemic and recession curves. Mitigating the COVID economic crisis: Act fast and do whatever, 31(2), 57-62.

Received: 1-Dec-2025, Manuscript No. JEEER-26-16822; Editor assigned: 10-Dec-2025, PreQC No. JEEER-26-16822(PQ); Reviewed: 15-Dec-2025, QC No. JEEER-26-16822; Revised: 20-Dec-2025, Manuscript No. JEEER-26-16822(R); Published: 27-Dec-2025