Research Article: 2026 Vol: 30 Issue: 2

The Impact Of Regional Accents On Perceived Managerial Competence And Career Growth In Indian Organizations

Archana Jog, Sunrise University, Alwar, India

Citation Information: Jog, A. (2026). The impact of regional accents on perceived managerial competence and career growth in indian organizations. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 30(S2), 1-9.

Abstract

In countries like India, where a mix of languages and cultures work through robust combination, accents play a crucial role. They become means of judging skills at work, reflecting leadership skills and a lot of time impacting the ability to climb the ladder. This study tries to explore that entire mesh. It fetches some eye-opening insights about the biases existing in the system. India, is not just another country but it is actually a web of dozens of languages. To add to the whole jumble, there are all those regional dialects. When people move for jobs, their accents tag along. It is typically observed that in work spaces, especially in larger organizations and cities, everyone tries to acquire a neutral tone of language. If your accent hints at coming from some smaller space in Bengal or Telangana, it sticks out in crowd. Nobody says it out loud. But it marks you. This study goes deeper than just skimming through this circus. The study is conducted through survey reaching out to 350 workers across different companies. Also an overview of some one-on-one discussions with 25 managers and HR personnel is analysed. It was very evident that accent bias is more commonly observed impacting jobs in India. It messes with people quiet strongly. Managers show clear leans in hiring. They skip candidates over accents. They worry about certain accents appearing unsophisticated or that it won't fit customer centric roles. It is also perceived that accent show a reverse impact on chances of promotions, especially to leadership roles where certain accent profiles are generally preferred. This keeps subtle but widespread corporate hierarchies that negatively impact people with non-metropolitan or rural accents. This bias is made worse by the fact that smart people from different language backgrounds can't easily get to important pipeline roles that lead to profit-and-loss management jobs. The biases make it much harder for them to move up in their careers. These systemic biases make meritocracy less effective, generating a "glass cliff" and changing what it means to be successful in a career. The effect is real: accent influences job access, promotions, and pay raises, which shows how important it is for HR professionals and executives to carefully look at and change how things are done now. Institutions that talk a lot about justice and diversity often forget that accent bias is a real and a prominent problem. It's crucial to raise awareness of these micro-prejudices in human resources and leadership programs, not merely to check the "inclusion" boxes, but also to truly increase the number of people who can do the job. The bigger effect on society is also important: making it so that varied styles of speech are not only allowed but also valued can help close gaps that have existed for a long time between regions and classes.

Keywords

Regional Accents, Managerial Competence, Career Growth, India, Workplace Diversity, Linguistic Bias.

Introduction

Language in India isn’t just about exchanging information; it’s woven into every aspect of how societies operate. With more than twenty officially-recognized languages and a crazy patchwork of accents and dialects, the way someone sounds when they speak is practically a pair of binoculars zooming into people’s origins, education, and social position. It’s fascinating how something as basic as an accent can unlock or shut so many doors Coupland, (2016). In India’s corporate world, English is indeed the language of the boardroom, but the flavour of English language spoken reflects a lot more than just the linguistic skills. People notice these details more than they admit, and it quietly steers a lot of decisions who gets the job, who gets picked for fancy overseas projects, who managers actually listen to in meetings. Sometimes, it’s not even intentional. Unconscious biases sneak in: one accent might get a label of “professional,” while another ends up unfairly tagged as “rustic” or “local”. As a result Qualified, candidates can be side-lined in favour of others sounding “right.” Western countries have published a lot of research showing accent bias affecting career prospects and impacting the climb up the corporate ladder. Strangely, in India a place where language is even more of a minefield very little data is available.

It is really surprising since the stakes are arguably higher here due to the sheer number of linguistic identities intersecting every day. This paper steps into that gap. It doesn’t just ask whether accent bias exists in Indian organizations it actually zooms into how it shapes perceptions of managerial competence, leadership potential, and overall perception building at work places Deprez-Sims & Morris, (2010). Are HR managers subconsciously filtering candidates based on how “polished” their English sounds? Is someone getting passed up for a promotion because their accent doesn’t “fit” with upper management? And how does all this interact with a lot of talk about being unbiased and inclusive and equity? It’s pretty clear that ignoring linguistic bias lets unequal structures quietly persist under the surface, even as organizations put on an inclusive face. To sum it up, the research aims to unmask how regional accents operate as both obvious and subtle gatekeepers impacting growth, progress, attention in Indian business. The hope is, by making these patterns more visible, businesses might be able to handle some of the deep-rooted exclusion wrapped up in “how you sound.”

Literature Review

Accents aren’t just background noises in workplace interactions they’re loaded signals. The body of research spanning sociolinguistics, organizational psychology, and even a bit of anthropology, consistently highlights how accents operate as both communicative shortcuts and instant social badges. A wealth of international scholarship has dug into these dynamics. In Western and notably multicultural settings, accents frequently map onto deeper assumptions about class, education, and even trustworthiness. For instance, a “standard” or “neutral” accent is often equated with competence or leadership potential. Meanwhile, speakers with regional, ethnic, or “non-mainstream” accents face subtle penalties ranging from being sidelined in meetings to missing out on promotions, no matter their actual skills. There’s a mind-boggling diversity of languages and accents colliding in Indian offices, yet the research specifically examining Indian workplace accent dynamics is surprisingly thin. That’s a serious gap, because linguistic hierarchy in India isn’t only about which language is spoken, but about whose accent carries “prestige” or signals belonging to an elite group. North or South, urban or rural, English or Hindi those nuances shape whose ideas are heard, whose authority gets challenged, and whose soft skills are written off Gluszek & Dovidio, (2010). This next section dives into the main theoretical frameworks that have tried to untangle all this. There’s more going on beneath the surface than just words; the way people speak might be pushing careers forward Lev-Ari & Keysar, (2010).

Accents, act as much more than just differences in pronunciation they’re loaded cultural markers. When you walk into a room and start speaking, your accent signals a whole raft of assumptions about where you come from, who you “belong” with, and, bizarrely enough, even how smart or trustworthy you might be. It’s not just a case of “Oh, that person sounds different” these judgments can seriously influence everything from social acceptance to hiring decisions. Lippi-Green, (2012) digs deep into this, highlighting how accents operate as badges of identity, linking people to specific regions or communities, and sometimes erecting social barriers as well. People claim to be unbiased, but research keeps showing that even highly trained professionals make snap judgments about others’ competence and trustworthiness based on little more than a vowel or two. And these biases don’t just shape individual interactions; they become baked into institutional practices, affecting who gets opportunities and who gets sidelined. The implications for social mobility, representation, and equity are massive. So, while it might seem superficial on the surface, accent prejudice is tangled up with deeper issues of power, belonging, and identity in society. Absolutely, digging deeper into what Hosoda & Stone-Romero (2010) uncovered reveals something honestly pretty unsettling about how Western labour market’s function when it comes to accent bias Neeley, (2013). Non-standard or foreign-accented speakers, regardless of their actual skills or qualifications, regularly face tangible hurdles right out of the gate. This isn’t just about hiring it seeps into pay checks and how fast people can climb the ladder too. It’s not merely language comprehension that trips people up, it’s the judgments about competence, intelligence, or even trustworthiness someone makes the moment they hear an accent that doesn’t fit the standard Mold. This bias doesn’t stop at basic employment or wage gaps it gets even stickier in leadership settings. People immediately think of the "standard" accent as a sign of authority and competence. A widespread bias connects certain sound qualities to ideas about leadership, which makes it harder for people with foreign accents to get jobs. Empirical research indicates that these candidates are frequently disregarded for promotions, excluded from leadership roles, and marginalized in decision-making processes, while having similar qualifications. Corporate setups end up pushing certain ways of talking over others. That just keeps those social unfairness issues rolling along. Thing is, companies that actually give a damn about fairness should not lean on some standard accent like it's this supposedly fair way to judge how well someone communicates. They need to dig into those old biases and push back against them on purpose. Take the job world in India for example. There a neutral sounding or city-style English accent basically means you're set for career wins. Folks with that urban way of speaking English get perks right off the bat. People see them as sharper, smarter, even more in the know sometimes. All that even when it has nothing to do with what they really bring to the table in skills or smarts. This tendency also has its roots in the deep historical legacies of colonialism and the idea that metropolitan affiliations signal modernity and sophistication. Conversely, accented English in regional accents, especially those associated with rural identities, is often viewed negatively or with some level of denial. These regional accents (Annamalai, 2004), when not capitalized on for their considerable linguistic variation, may lead to speakers being excluded from, or at least never fully included within, certain social groups, such as the elite. It is also noticed that the context of employment;

Theoretical Framework

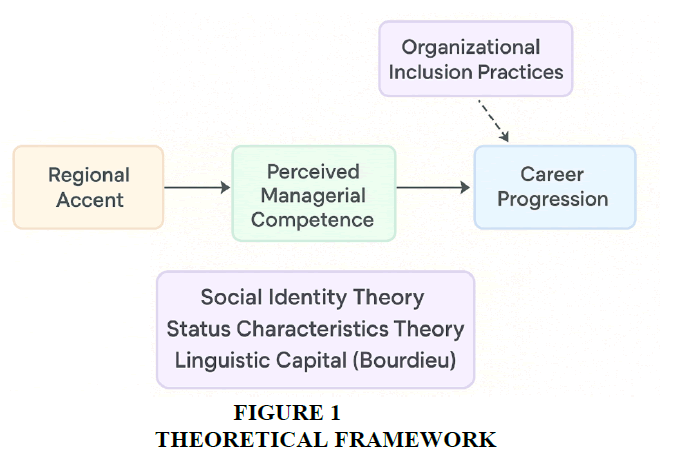

This study explores three interrelated theoretical perspectives which collectively present how accent operates as a sociolinguistic indication influencing perceptions towards managerial competence and impact career growth.

(a) Social Identity Theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979): According to this theory, people categorize others into “in-groups” and “out-groups” based on identifiable traits like language or accent. Typically in Indian organizations, speakers with metropolitan or “neutral” English accents are subconsciously counted as in-group members, clearly indicating more suitable for higher competence and leadership roles. In contrast, those with regional or rural accents may be perceived as less authoritative, resulting in biased treatment towards managerial assessments.

(b) Status Characteristics Theory (Berger et al., 1977): This theory suggests that certain attributes— such as gender, appearance, or linguistic markers—function as status cues impacting assessments of capability. A “standard” accent works as a status characteristic, highlighting professionalism, cognitive ability, and leadership potential. Accent thus becomes a misunderstood signal shaping managerial judgments and promotion opportunities.

(c) Linguistic Capital and Symbolic Power (Bourdieu, 1991): In multilingual societies like India, the way one speaks reflects a lot of aspects. Accents represent linguistic capability that can be converted into social and economic advantage. Those who possess “prestige accents” obviously get easier access to leadership roles, while others experience linguistic side-lining. Therefore, Accent bias is believed to promote structural inequalities camouflaged under merit based systems.

Together, these frameworks clarify how regional accent functions as both a symbolic asset and a barrier within organizational hierarchies. The study’s conceptual model Figure 1 integrates these hypotheses into a testable framework linking accent type, perceived managerial competence, and career progression, moderated by organizational inclusion practices.

Research Gap

Although numerous personal accounts and media reports highlight the existence of accent-based discrimination in India, there remains a notable lack of rigorous empirical research. This study seeks to address this gap by systematically examining the impact of regional accents on managerial judgments and career advancement within Indian organizations.

Research Objectives

i. To examine the extent to which regional accents affect perceptions of managerial competence in Indian organizations.

ii. To analyse the impact of accent bias on career progression and leadership opportunities.

iii. To identify the underlying stereotypes associated with different regional accents.

iv. To propose organizational strategies to mitigate accent-based discrimination.

Methodology

This article adopts a mixed-methods approach to develop a nuanced understanding of the impact of regional accents on evaluations of managerial prosocial competence and actual managerial advancement. Combining quantitative survey data with qualitative interview data effectively captures the complex nature of bias in various company contexts. This convergence of methods allows for a thorough exploration of both the general trends in the data and the lived experiences of individuals, resulting in a more complete picture of how accent-based disparities affect career trajectories Ramanathan, (2005).

Research Design

A mixed-methods approach was adopted, integrating quantitative surveys and qualitative interviews.

Sample

Surveyed 350 people from the busy metropolitan area of Delhi who worked in IT, finance, education, and manufacturing. That took care of the numbers. For the qualitative part, I did 25 in-depth interviews with managers, HR professionals, and employees. I made sure to include a variety of regional accents to get a wider range of perspectives and deeper insights Table 1.

| Table 1 Sample | ||||

| Method | Sample Size | Participants | Sector/Location | Focus |

| Quantitative Survey | 350 | Employees | IT, Finance, Education, Manufacturing (Delhi) | Measured perceptions of managerial competence across accents |

| Qualitative Interviews | 25 | Managers, HR professionals, and employees | Delhi (metropolitan hub) | Explored deeper insights on accent bias, recruitment, and promotion |

Instruments

Measures of accent bias in the pre-screening and rating process: survey. Online survey measuring perceptions of competence, leadership potential, and expect promotions across 3 different accents using Likert-scale questions and open-ended response qualitative demographic measures. Measures of accent bias in the pre-screening and rating process: interviews. Semi-structured interview guide used for qualitative interviews designed to elicit detailed personal narratives of experiences with accent bias in occupational contexts. Includes probes to encourage further elaboration and follow-up questions.

Data Analysis

Quantitative data were processed using SPSS for descriptive statistics, regression analysis, and ADECA. Qualitative data underwent thematic coding via NVivo.

Research Objectivity and Validation

To achieve methodological robustness, the study ensured reliability and validity across both quantitative and qualitative components.

Instrument Validation: The survey items were adapted from validated scales on linguistic bias and leadership perception (Fuertes et al., 2012; Hosoda & Stone-Romero, 2010). A pilot test with 30 respondents yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.86, confirming internal consistency.

Sampling Rationale: Delhi was chosen due to its cosmopolitan workforce and linguistic diversity, providing an ideal setting to capture accent variation. Stratified purposive sampling ensured representation across North, South, East, and West Indian speech backgrounds.

Data Analysis Rigor

• Quantitative data were analysed through multiple regression models predicting perceived managerial competence from accent, education, and gender.

• ADECA tests compared mean competence ratings across regional groups.

• Qualitative interviews were transcribed verbatim and coded in NVivo using an inductive thematic approach.

• Inter-coder reliability (Cohen’s κ = 0.81) confirmed coding consistency.

• Triangulation between datasets enhanced interpretive validity.

Findings

This section presents the results from both the quantitative survey and qualitative interviews, highlighting how regional accents influenced perceptions of managerial competence and career progression in Indian organizations.

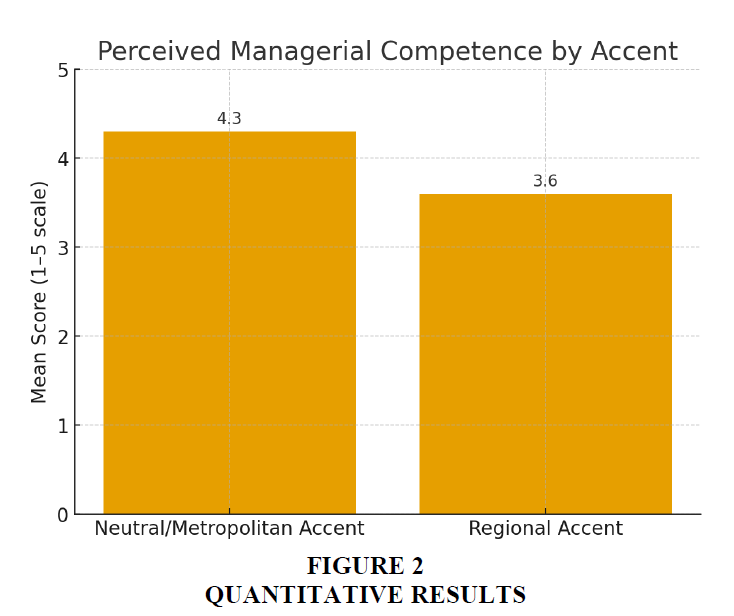

Quantitative Results

Statistically significant correlation emerged between accent and perceived managerial competence, with individuals possessing neutral or metropolitan accents receiving notably higher ratings (mean score: 4.3) than those with pronounced regional accents (mean score: 3.6). This research suggests that accent bias contributes significantly to assessments of leadership potential, explaining approximately 18% of the observed variation. Study participants also expressed a clear preference for candidates with neutral accents during both hiring and promotional evaluations, reinforcing the implications of accent bias in career advancement Figure 2.

Qualitative Results

Respondents from rural and semi-urban backgrounds described experiencing ridicule or correction regarding their accents during professional interactions. While HR professionals stated that accent is not explicitly listed as a hiring qualification, they acknowledged its subtle impact on perceptions of professionalism and readiness for client-facing roles. Some managers classified accent as a "soft skill" that could influence communication effectiveness, even when technical abilities are comparable among candidates.

Regression analysis revealed that accent significantly predicted managerial competence (β = 0.42, p < .001) even after controlling for education, experience, and gender. The model explained 18.7% of variance (R² = .187) in competence ratings. ADECA results indicated that respondents with neutral accents were rated significantly higher (M = 4.3) than those with strong regional accents (M = 3.6), F(2,347) = 9.72, p < .01.

Thematic analysis identified three recurring narratives

• Accent as a Soft Skill: HR professionals associated accent neutrality with communication skill.

• Self-Consciousness and Identity Suppression: Employees consciously modified their accents to “fit in.”

• Structural Exclusion: Accent bias subtly offered access to customer-facing and leadership opportunities.

Discussion

The findings support global evidence on linguistic discrimination but applies it to the multilingual Indian context. Accent works not just as a phonetic variation but as a symbolic indicator of personality and hierarchy. The results support Social Identity Theory, clearly indicating that individuals with neutral or metropolitan accents are accepted as part of an in-group associated with professionalism and competence. On the contrary, regional accents point to out-group perceptions, leading to subtle exclusion from leadership pipelines.

In agreement with Status Characteristics Theory, accent serves as an implicit status signal that build expectations of ability. The overvaluation of certain accents reiterates linguistic elitism and may wear down the credibility of otherwise capable managers. From a Bourdieusian perspective, linguistic capital works as a gatekeeping mechanism: those possessing “high-status” linguistic skills enjoy unjustified advantages in promotions and evaluations.

This study highlights how accent bias overlaps with class, geography, and education to reinforce systemic inequality within Indian organizations. The findings contribute a new perspective to diversity and inclusion literature by presenting accent as a critical but unnoticed dimension of workplace bias.

Managerial And Policy Implications

For Human Resources and Organizational Leaders

• Incorporate accent awareness into diversity and inclusion contexts, ensuring unbiased practices of recruitment and promotion assessments.

• Conduct accent-neutral language usage workshops that highlight clarity and empathy over use of elite speech patterns.

• Develop inclusive language policies identifying linguistic diversity as a strategic advantage.

For Learning and Development

• Develop focused modules on unconscious linguistic bias as a part of leadership development programs.

• Initiate mentorship and coaching initiatives valuing regional speech styles, emphasizing psychological safety and feeling of belongingness.

• Such measures can convert linguistic diversity into a source of developing cross-cultural competence rather than working as a barrier to leadership development.

Limitations And Directions For Future Research

• The sample was limited to the Delhi region, which may not represent linguistic perceptions across India’s diverse corporate landscapes.

• The reliance on self-reported data presents possible social desirability bias.

• Future studies could employ experimental designs to separate fundamental effects of accent.

• Expanding the scope of study to include multiple supporting factors like gender, region, and class could offer a deeper understanding of different perspectives to linguistic inequality.

• Longitudinal exploratory research could initiate a study about relationship between of accent adaptation over time and career outcomes.

Conclusion

Accent prejudice shows up in Indian companies. It messes with meritocracy in a small way, but it's still pretty significant. Thing is, it links how people from different regions talk to judgments about their skills or if they can lead. There's this quiet push for what counts as a standard accent. You hear it all the time on national TV or news. That just makes the bigger inequalities even worse. It's not some shallow issue. It points to how power and social setups run deep in society. Companies that demand everyone speaks the same way end up killing off different ideas. Those varied views are what drive new thinking and inDecation. Instead, you get a setup where fitting in beats being yourself. That drags down people's spirits. It also makes the business struggle more over time. To really fix things, you need solid policies tackling accent bias from start to finish. That means hiring all the way to promotions. Not those half-hearted diversity nods. Workers should get regular training. It helps them spot their own biases and handle them. Bosses have to lead by example. They need to back different ways of speaking. Show how to talk without judging accents. India boasts all these languages. Still, folks with local accents face rough going at work. Getting rid of this bias matters ethically. It's smart strategy too. Companies can tap into India's rich language mix. That builds real creativity. Better teamwork. Growth that lasts.

References

Coupland, N. (Ed.). (2016). Sociolinguistics: theoretical debates. Cambridge University Press.

Deprez-Sims, A. S., & Morris, S. B. (2010). Accents in the workplace: Their effects during a job interview. International Journal of Psychology, 45(6), 417-426.

Fuertes, J. N., Gottdiener, W. H., Martin, H., Gilbert, T. C., & Giles, H. (2012). A meta-analysis of the effects of speakers' accents on interpersonal evaluations. European journal of social psychology, 42(1), 120-133.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Gluszek, A., & Dovidio, J. F. (2010). Speaking with a nonnative accent: Perceptions of bias, communication difficulties, and belonging in the United States. Journal of language and social psychology, 29(2), 224-234.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hosoda, M., & Stone-Romero, E. (2010). The effects of foreign accents on employment-related decisions. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 25(2), 113-132.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lev-Ari, S., & Keysar, B. (2010). Why don't we believe non-native speakers? The influence of accent on credibility. Journal of experimental social psychology, 46(6), 1093-1096.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lippi-Green, R. (2012). English with an accent: Language, ideology and discrimination in the United States. Routledge.

Neeley, T. B. (2013). Language matters: Status loss and achieved status distinctions in global organizations. Organization Science, 24(2), 476-497.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ramanathan, V. (2005). The English-vernacular divide: Postcolonial language politics and practice (Vol. 49). Multilingual Matters.

Received: 01-Dec-2025, Manuscript No. AMSJ-25-16335; Editor assigned: 02-Dec-2025, PreQC No. AMSJ-25-16335(PQ); Reviewed: 15-Dec-2025, QC No. AMSJ-25-16335; Revised: 19-Dec-2025, Manuscript No. AMSJ-25-16335(R); Published: 24-Dec-2025