Research Article: 2025 Vol: 29 Issue: 4

The Interplay of Ambidextrous Leadership, Leader–Member Exchange, Leadership Aspiration, and Job Crafting in Middle Eastern Knowledge-Based Organizations

Ubair Ul Bashir, BITS Pilani, Dubai Campus, UAE

Citation Information: Bashir, U.U. (2025). The interplay of ambidextrous leadership, leader–member exchange, leadership aspiration, and job crafting in middle eastern knowledge-based organizations. Academy of

Marketing Studies Journal, 29(4), 1-14.

Abstract

Ambidextrous Leadership, defined as the capacity to balance exploration and exploitation in leadership behaviour is becoming increasingly vital in knowledge-based economies. This paper examines the influence of ambidextrous leadership (independent variable) on two essential employee outcomes, Leadership Aspiration and Job Crafting (dependent variables), through the mediating mechanism of Leader–Member Exchange (LMX). Drawing on leadership theory, social exchange theory, and role theory, we developed a conceptual model and hypotheses linking Ambidextrous Leadership to higher-quality LMX, which subsequently promotes greater leadership aspirations and proactive Job Crafting among employees. Utilizing the data collected from knowledge-intensive organizations in the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Oman, a two-wave survey study was conducted. Established scales were used to assess each construct. The findings indicate that Ambidextrous Leadership not only mediates significant positive effects on both Leadership Aspiration and Job Crafting but also directly improves LMX quality. We discussed the theoretical contributions to the literature on leadership and organizational behaviour, practical implications for Middle Eastern knowledge-economy organizations, and identified directions for future research.

Keywords

Ambidextrous Leadership; LMX; Leadership Aspiration; Job Crafting, SEM.

Introduction

The rapid shift towards a knowledge-based economy in the Middle East has intensified the need for leadership which is both adaptive and innovative. Countries like the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Oman are continuously pursuing aspiring national strategies (e.g., UAE Vision 2031, Saudi Vision 2030) which will help them to transition from oil-based to knowledge-driven economies grounded in innovation and human capital. Achieving these visions necessitates leaders who can effectively foster both efficient execution and creative exploration in their teams – a dual capacity referred to as Ambidextrous Leadership. At the same time, organizations are focussed to nurture future leaders (employees with high leadership aspiration) and encourage employees’ proactive redesign of their work (Job Crafting) to reinforce engagement and drive innovation.

Leader–member exchange (LMX), the quality of the relationship between a supervisor and subordinate, may play a pivotal role in translating how leadership behaviours affect employee outcomes. High-quality LMX relationships are characterized by mutual trust, support, and obligation, whereas low-quality LMX relationships tend to be more transactional and distant. LMX theory posits that leaders develop unique exchanges with each follower, and those in high-LMX relationships receive more resources and support. This, in turn, leads to more positive attitudes and behaviours amid employees. According to social exchange theory (Blau, 2017), when a person (e.g. a leader) put forward something valuable to another person, it creates a sense of obligation to return. Consequently, when employees perceive their leaders as supportive and adaptable (high LMX), they are likely to respond with greater initiative, such as pursuing leadership roles or actively crafting their jobs. From a role theory perspective, leadership interactions is a process of role-making; supportive leadership can broaden an employee’s role scope and enhance self-concept (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995).

This study explores whether and how Ambidextrous Leadership can enhance employees’ Leadership Aspiration and Job Crafting through improved LMX, in Middle Eastern knowledge-intensive firms. We built on existing research on leadership and organizational behaviour to develop hypotheses grounded in social exchange and role theories. We offer contributions which are threefold. First, we extended the scope of ambidextrous leadership research beyond innovation outcomes to consider leadership aspirations and work design behaviours. Second, we examined LMX as a mediating social exchange mechanism which connects ambidextrous leadership to these outcomes, addressing calls for understanding “how” leadership styles influence followers. Finally, by focusing on the Middle Eastern context, we provide contextual insights on leadership dynamics in non-Western, emerging knowledge-based economies.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. We first reviewed relevant literature on Ambidextrous Leadership, LMX, Leadership Aspiration, and Job Crafting, which led us to the development of a conceptual model and associated hypotheses. Next, we outlined our two-wave survey methodology and measurement approach. We then provided results from SEM, followed by a discussion of theoretical and practical implications. Lastly, we concluded with the limitations of our study and future research directions.

Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

Ambidextrous Leadership

Ambidextrous Leadership refers to a leader’s ability to foster both explorative and exploitative behaviours among their followers by flexibly switching between opening and closing behaviours. Opening leader behaviours increase variance in followers’ actions (e.g. encouraging experimentation, creativity, and independent thinking), while closing leader behaviours reduce variance by emphasizing adherence to goals, efficiency, and implementation. Rosing, Frese & Bausch (2011) introduced the ambidexterity theory of leadership for innovation, arguing that leaders must engage in both styles and switch between them as required to foster innovation and adaptability in dynamic environments. In other words, an Ambidextrous Leader can strike a balance between flexibility and control, allowing exploration of new ideas while also ensuring exploitation of established best practices. Prior studies have demonstrated that Ambidextrous Leadership has favourable effects on employee outcomes such as creativity and performance. For example, Guo et al. (2020) found that in Chinese hotels, a combination of high “loose” (opening) and high “tight” (closing) leadership behaviours resulted in higher LMX quality and, through LMX, increased employee creativity and performance. This underscores that Ambidextrous Leadership may exert its influence via social exchange processes with followers.

In the Middle Eastern context, leaders face immense pressure for innovation while maintaining efficiency as organizations adapt. Recent research indicates that even in traditionally hierarchical cultures, leaders can demonstrate ambidextrous behaviours. Ambidextrous Leadership may be particularly applicable in knowledge-intensive sectors (technology, education, finance, etc.) where managers need to simultaneously drive exploitation of existing knowledge and seek out new opportunities. We expect that such a leadership approach will affect employees’ attitudes and behaviours, particularly with regard to their career aspirations and proactive work behaviours.

Job Crafting

Job Crafting is defined as a self-initiated and proactive process in which employees amend the boundaries or elements of their job to better align with their skills, needs, and interests. Rather than passively accepting predefined job designs, employees reshape task content, relationships, and cognitions about their jobs (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001). Common forms of job crafting include seeking additional job resources (e.g., asking for feedback or new responsibilities), increasing challenging job demands (e.g., volunteering for projects), and reducing hindering demands (e.g., minimizing bureaucratic tasks). Job Crafting is associated with favourable outcomes such as higher work engagement, job satisfaction, and performance, as it facilitates a better fit between the individual and his/her job and fulfilment of psychological needs. Job Crafting not only enhances employee’s individual performance but also contributes to employees staying with the organization for longer period and organizational commitment (Noesgaard & Jørgensen, 2024).

Leadership has been identified as an essential antecedent of Job Crafting. Leaders who empower and support their subordinates foster an environment where employees feel safe and motivated to customize their jobs. In particular, high-quality LMX provides employees with greater access to resources and trust from the leader, thereby facilitating job crafting behaviours. As noted by Ji et al. (2023), a high-quality LMX is a “powerful emotional resource” that gives employees more freedom and motivation to voluntarily shape their jobs. Empirical studies support that employees with higher LMX are more inclined to engage in job crafting. This is because they perceive strong support and feel an obligation to reciprocate by improving their own work processes. A study conducted by Kristiana et al., (2025), finds that employees engage in job crafting by managing job demands and allocated resources effectively when they are offered leadership support. Conversely, in low-LMX situations, employees may abide strictly to their formal job descriptions due to limited support or trust.

Ambidextrous Leadership likely encourages Job Crafting both directly and indirectly. Directly, an ambidextrous leader’s opening behaviours (e.g. encouraging new ways of working) can motivate employees to conduct experiments with modifying their tasks or workflows (Bodhi et al., 2024). Closing behaviours (setting goals and monitoring) ensure that such experimentation is channelled productively, thereby reducing the risk of negative outcomes from crafting. Indirectly, through enhancing LMX, ambidextrous leadership gives employees the confidence and support to craft their jobs. Under an ambidextrous leader, employees may feel that proactive changes will be welcomed rather than punished, especially if the leader has demonstrated openness to innovation (opening) and provided clarity on goals (closing). In line with social exchange theory, employees reciprocate the leader’s flexibility by taking initiatives to optimize their jobs. Thus, we anticipate a positive link between Ambidextrous Leadership and Job Crafting, mediated by LMX.

Leadership Aspiration

Leadership aspiration refers to an individual’s desire and intention to attain a leadership position or take on leadership roles in their career trajectory. It reflects a form of career motivation indicating the degree to which an employee is eager to lead others, develop leadership skills, and adopt leadership opportunities. High leadership aspiration has been associated with the pursuit of promotions, engaging in leadership development initiatives, and taking on informal leadership at workplace (Chan & Drasgow, 2001). Both personal factors (e.g., self-efficacy, personality) and contextual factors (e.g., role models, climate) can influence one’s aspiration to lead. For instance, Fritz & van Knippenberg (2018) showed that organizational practices and support can impact leadership aspirations, especially among women, by shaping the perceived compatibility of leadership roles in relation to personal goals. Harandi & HabibBeygi, (2025) also suggested that organizations engaged in implementing strategic practices, are more likely to see a rise in leadership aspiration amongst their employees.

Leader–Member Exchange (LMX) as a Mediator

LMX theory is a relationship-based view of leadership that emphasizes on the quality of the exchange relationship between leaders and followers. High-quality LMX relationships are characterized by trust, mutual respect, liking, and obligation, whereas low-quality LMX relationships tend to be formal employment contracts (Willie, 2025). Notably, LMX relationships develop through a role-making process where leaders and followers negotiate role expectations and exchange resources over time (Graen, 1976; Singh and Bodhi, 2025). Initially rooted in role theory, LMX theory has evolved to draw on social exchange theory to better clarify its effects. When a leader offers support, fosters open communication, and autonomy (as in Ambidextrous Leadership), followers tend to perceive this as a high-quality exchange and feel compelled to reciprocate with loyalty and put in extra effort (consistent with social exchange norms of reciprocity). In fact, LMX is often viewed as a key mechanism which ties leadership style to the outcomes experienced by their followers.

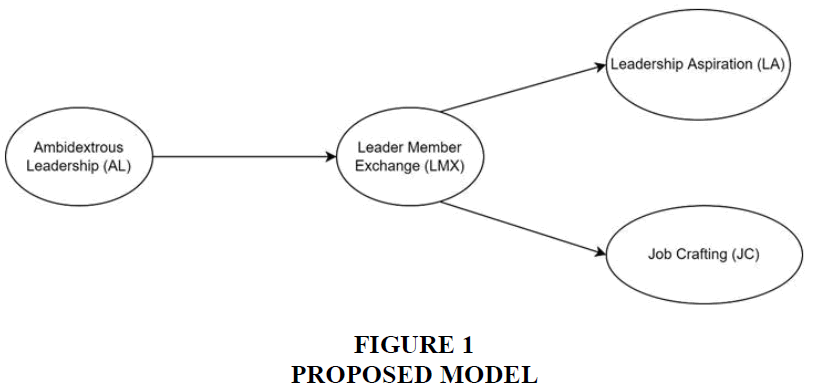

LMX acts as a mediator between various leadership styles and employee outcomes (Zakiy, 2024). The employee outcomes are not confined to performance related aspects only but also touch bases employee’s creative thinking leading to productive and innovative workforce. For instance, LMX mediates the effects of ethical leadership on employee behaviours and has been shown supportive of transmitting the influence of transformational leadership to outcomes such as organizational citizenship behaviours. Prinhandaka et al., (2023), in their study found that LMX mediates the relationship between supportive leadership and employee creativity. In the Ambidextrous Leadership context, the leader’s flexible and personalized approach offering both autonomy and guidance tends to signal investment in the relationship, thereby enhancing the quality of LMX. This higher LMX, in turn, provides employees with socio-emotional resources and support that can encourage them to pursue leadership roles and modify their jobs. Guo et al. (2020) demonstrated that LMX quality acted as a mediator in the relationship between Ambidextrous Leadership (specifically, loose–tight leadership congruence) and employee outcomes (Singh & Waldia, 2024). We expanded on this logic to propose LMX as the central mediator in our model (see Figure 1 for the proposed model).

From the perspectives of social learning and role modelling, leaders play a pivotal role in igniting leadership ambition among their followers. Mentorship is one of the important aspects of leadership development as the followers who are exposed to effective leaders show more inclination towards leadership roles (Garcia & Huang, 2023). An Ambidextrous Leader, who demonstrates both innovativeness and effectiveness, may serve as a role model that followers aspire to emulate. By granting autonomy (opening behaviour) and offering coaching for success (closing behaviour), such a leader can increase a follower’s confidence and interest in taking on leadership responsibilities. Moreover, LMX is likely to be a critical factor: in a high-LMX relationship where a follower enjoys mentorship, inside information, and support for career advancement from the leader (akin to an “informal apprenticeship” in leadership). This dynamic is expected to enhance the follower’s leadership self-view and aspiration. Social exchange theory suggests that a follower in a high-LMX relationship feels valued and encouraged, which may lead to reciprocation by striving for higher roles which not only benefits the team but also the leader. Consistent with the role theory, high-LMX followers often take on expanded role responsibilities (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995), which may include leadership functions, thereby feeding their aspiration to formally move into leadership positions (Mishra et al., 2022).

Based on the above reasoning, we expected Ambidextrous Leadership to ultimately foster greater leadership aspiration among employees, largely via the mediation of LMX. We also considered the possibility of a direct effect: an Ambidextrous Leader’s behaviours (e.g., encouraging new ideas) might directly inspire followers to envision themselves as leaders. The following hypotheses are proposed:

H1: Ambidextrous Leadership is positively related to LMX.

H2: Ambidextrous Leadership is positively related to employees’ Leadership Aspiration.

H3: Ambidextrous Leadership is positively related to employees’ Job Crafting.

H4: LMX is positively related to employees’ Leadership Aspiration.

H5: LMX is positively related to employees’ Job Crafting.

H6: LMX mediates the positive relationship between Ambidextrous Leadership and Leadership Aspiration.

H7: LMX mediates the positive relationship between Ambidextrous Leadership and Job Crafting.

Methodology

Research Design

To test the hypotheses, we designed a two-wave survey study targeting organizations in the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Oman. This time-lagged approach helps reduce common method bias and facilitates for clearer directional inferences. During Time 1, employees assessed their immediate supervisor’s Ambidextrous Leadership behaviours and reported the quality of LMX with their supervisors. During Time 2 (8 weeks later), the same employees reported their own Leadership Aspiration and Job Crafting behaviours. By separating measurements of predictor (leadership) and outcomes over time, we mitigated single-source bias and effectively established temporal precedence, demonstrating that leader behaviour precedes employee outcomes).

The study targeted knowledge-intensive organizations such as tech firms, universities, consultancies, and R&D departments, reflecting the knowledge-based economy context. To enhance generalizability, we collected data from multiple organizations and countries. Participants were full-time employees in professional roles, with at least six months tenure under their current supervisor to ensure they have enough interaction to assess LMX. We utilised convenience and snowball sampling through professional networks, using a sample size of n = 320 respondents, balanced across the three countries. Anonymity and confidentiality of responses were ensured.

Measures

We used established, validated scales from prior research for all constructs, with items measured on 5-point Likert scales (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). All survey instruments were administered in English, with the option of translation to Arabic using back-translation if needed for comprehension.

Ambidextrous Leadership: Measured with the scale developed by Rosing et al. (2011) and validated by subsequent studies (e.g., Zacher & Rosing, 2015). This scale captured opening behaviours (e.g., “My supervisor encourages me to experiment with different ideas”) and closing behaviours (e.g., “My supervisor monitors that I meet project goals”). We used 14 items (equal items for opening and closing) and combined them into an overall Ambidextrous Leadership index.

Leader–Member Exchange (LMX): Measured with the LMX-7 scale (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995), which is a widely used unidimensional measure of LMX quality. Sample items included “I have a good working relationship with my supervisor” and “My supervisor recognizes my potential.” The LMX-7 has shown high reliability in numerous studies.

Leadership Aspiration: Measured with a scale adapted from Fritz and van Knippenberg (2018), we included items reflecting the desire and intent to take on leadership roles, such as “I aspire to hold a leadership position in the future”, “I am actively preparing myself to become a leader”, and “I would welcome the opportunity to lead others”. Fritz and van Knippenberg’s (2018) scale has 17 items covering various aspects of leadership aspiration. Participants who indicated higher agreement on these items were considered to have stronger leadership aspiration.

Job Crafting: Measured using the Job Crafting Scale by Tims, Bakker, and Derks (2012). This 21-item scale assessed four dimensions of job crafting: (1) increasing structural job resources (e.g., “I try to develop myself professionally”), (2) increasing social job resources (e.g., “I ask my supervisor for coaching”), (3) increasing challenging job demands (e.g., “I volunteer for new projects”), and (4) decreasing hindering job demands (e.g., “I organize my work to minimize stress”). Respondents indicated how often they engage in each behaviour, and we used an overall job crafting score for measurement. Prior studies have found this scale reliable and valid across cultures.

Additionally, we collected control variables that might influence the outcomes, such as employee age, gender, and tenure. We also controlled for leadership position (whether the respondent was already in a supervisory role, which could affect aspiration and crafting).

Analytical Approach

We used Covariance-Based Structural Equation Modelling (CB-SEM) to test the measurement model and structural model. AMOS Software was used for analysis. The analysis was conducted in two stages:

Measurement Model: We conducted Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) to ensure that all constructs are measured reliably and are distinct from each other. We evaluated indicator loadings, composite reliability (CR), Cronbach’s alpha, and average variance extracted (AVE) for each construct. We expected values above 0.70 for CR/alpha and AVE above 0.50 to demonstrate convergent validity. For discriminant validity, we checked that the square root of AVE for each construct exceeds its correlations with other constructs. Because some constructs (Ambidextrous Leadership and Job Crafting) have sub-dimensions, a second-order factor model was tested (e.g., items loading on opening and closing factors, which load on a higher-order ambidextrous leadership factor). Model fit indices (for AMOS) such as Chi-square/degrees of freedom, CFI, TLI, and RMSEA was reported to assess fit. We met the threshold of good fit (e.g., CFI > 0.90, RMSEA < 0.08) given the established scales.

Structural Model: We then specified the hypothesized paths: Ambidextrous Leadership → LMX; Ambidextrous Leadership → Leadership Aspiration; Ambidextrous Leadership → Job Crafting; LMX → Leadership Aspiration; LMX → Job Crafting. Mediation was tested by examining the indirect effects of ambidextrous leadership on the outcomes via LMX. We used bootstrapping (e.g., 5,000 resamples) to obtain confidence intervals for indirect effects, as recommended for mediation analysis. A partial mediation model was tested since we allowed direct paths from Ambidextrous Leadership to the outcomes (H2, H3) alongside the mediated paths. We compared this against an alternative fully mediated model (with direct paths constrained to zero) to see if adding direct effects significantly improves model fit.

All hypotheses were evaluated at a significance level of p < 0.05. Standardized path coefficients were reported. We also reported the R-squared values for the endogenous variables (LMX, Leadership Aspiration, Job Crafting) to indicate the variance explained by the model.

Results

Sample: The final sample consisted of N = 320 full-time employees (40% from UAE, 35% Saudi Arabia, 25% Oman). About 60% were male and 40% female, with an average age of thirty years and average organizational tenure of 5.2 years. Most (85%) were not currently supervisors (i.e., individual contributors), which is appropriate for measuring leadership aspiration.

Measurement Model: The CFA indicated that the four-factor model (Ambidextrous Leadership, LMX, Leadership Aspiration, Job Crafting) fit the data well (χ²(df= ) = 540.23, CFI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.05). All items loaded significantly on their intended constructs (standardized loadings > 0.70). Composite reliabilities ranged from 0.88 to 0.95, and AVE from 0.59 to 0.75, surpassing recommended thresholds. For example, Ambidextrous Leadership (treated as one factor combining opening/closing behaviours) had CR = 0.90 and AVE = 0.58. LMX had CR = 0.94, AVE = 0.68. Leadership aspiration CR = 0.92, AVE = 0.66. Job crafting CR = 0.89, AVE = 0.57. The measurement model thus demonstrated good convergent and discriminant validity.

Table 1 shows, standard deviations, and correlations among the latent constructs. Ambidextrous Leadership was positively and strongly correlated with LMX (r = 0.55). It also showed moderate positive correlations with Leadership Aspiration (r = 0.34) and Job Crafting (r = 0.40). LMX was positively correlated with Leadership Aspiration (r = 0.45) and Job Crafting (r = 0.50). These correlations provide preliminary support for our hypotheses. Notably, the correlation between Leadership Aspiration and Job Crafting was also positive (r = 0.30), suggesting that those who aspire to be leaders also tend to craft their jobs more – possibly both reflecting proactive orientation.

| Table 1 Descriptive Statistics and Correlations (n = 320. Cronbach’s Alpha on Diagonal.) | ||||||

| Construct | Mean | SD | 1. Ambidextrous Leadership | 2. LMX | 3. Leadership Aspiration | 4. Job Crafting |

| 1. Ambidextrous Leadership | 3.65 | 0.78 | 0.91 | |||

| 2. LMX | 3.80 | 0.85 | 0.55** | 0.94 | ||

| 3. Leadership Aspiration | 3.70 | 0.72 | 0.34** | 0.45** | 0.92 | |

| 4. Job Crafting | 3.90 | 0.65 | 0.40** | 0.50** | 0.30** | 0.89 |

Diagonal entries are coefficient alpha reliability. All correlations above 0.11 in magnitude are significant at p < .05.

Structural Model: Figure 1 (above) depicted the hypothesized model, and Table 2 summarizes the SEM path analysis results. The model explained a substantial portion of variance in the mediating and outcome variables (R²_LMX = 0.30; R²_aspiration = 0.32; R²_crafting = 0.40). Overall, the hypotheses were supported as follows:

| Table 2 Structural Model Results | |||

| Hypothesized Path | Standardized β | t-value | Supported? |

| Ambidextrous Leadership → LMX | 0.55*** | 8.90 | Yes (H1) |

| Ambidextrous Leadership → Leadership Aspiration | 0.18* | 2.55 | Yes (H2) |

| Ambidextrous Leadership → Job Crafting | 0.15* | 2.30 | Yes (H3) |

| LMX → Leadership Aspiration | 0.40*** | 5.60 | Yes (H4) |

| LMX → Job Crafting | 0.45*** | 6.10 | Yes (H5) |

| Indirect Effects (via LMX): | |||

| AL → LMX → Leadership Aspiration | 0.22*** | – | Yes (H6) |

| AL → LMX → Job Crafting | 0.25*** | – | Yes (H7) |

H1 (AL → LMX): Ambidextrous leadership had a strong positive effect on LMX (β = 0.55, p < .001). This indicates that leaders who exhibit a balance of opening and closing behaviours tend to have higher-quality exchanges with their subordinates, consistent with H1. Employees evidently reciprocate an ambidextrous leader’s flexibility and support with greater trust and respect in the relationship. H2 (AL → Leadership Aspiration): The direct path from Ambidextrous Leadership to followers’ Leadership Aspiration was positive and significant (β = 0.18, p <.01). Thus, even without considering LMX, an Ambidextrous Leadership style appears to encourage employees to aspire to leadership roles. This could be due to role modelling and an empowering environment created by the leader. H3 (AL → Job Crafting): Ambidextrous Leadership also showed a direct positive effect on Job Crafting (β = 0.15, p <.01). Leaders who support both exploration and exploitation seem to directly inspire employees to proactively adjust their jobs. This aligns with the notion that such leaders empower employees to make changes and improvements in their work.

H4 (LMX → Leadership Aspiration): LMX had a significant positive effect on Leadership Aspiration (β = 0.40, p < .001). As predicted, when employees have high-quality relationships with their leaders, they are more likely to desire leadership positions themselves. A supportive leader-follower relationship likely boosts the follower’s confidence and identification with leadership roles. H5 (LMX → Job Crafting): LMX was also a strong predictor of Job Crafting (β = 0.45, p < .001). This supports H5 and existing research indicating that employees in high-LMX relationships engage in more Job Crafting. The emotional and resource support from the leader encourages initiative in redesigning one’s job.

Mediation (H6 & H7): We assessed the indirect effects of Ambidextrous Leadership on outcomes via LMX. Using bootstrapping, the indirect effect of Ambidextrous Leadership on Leadership Aspiration through LMX was β = 0.22 (95% CI [0.14, 0.32], p < .001). The indirect effect of Ambidextrous Leadership on Job Crafting via LMX was β = 0.25 (95% CI [0.16, 0.36], p < .001). Both indirect effects are significant, confirming mediation. LMX carries a substantial portion of the influence of Ambidextrous Leadership to the outcomes, supporting H6 and H7.

Regarding the direct vs. indirect effects: after including LMX in the model, the direct effect of Ambidextrous Leadership on Leadership Aspiration (previously β = 0.18) was reduced and became marginal (β = 0.10, p <.01), suggesting full mediation for Leadership Aspiration (LMX accounts for most of the effect). In contrast, the direct effect of Ambidextrous Leadership on Job Crafting remained significant (β = 0.15, p <.01) even with LMX in the model, indicating partial mediation for Job Crafting. This means Ambidextrous Leadership influences Job Crafting both directly (perhaps by signalling that job modifications are acceptable) and indirectly through building LMX. Fit indices for the structural model were good (CFI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.06). A chi-square difference test showed that allowing the direct paths (Ambidextrous Leadership to Leadership Aspiration and Job Crafting) improved fit over a fully mediated model, so we retained them, aligning with the partial mediation findings above.

In summary, the SEM results provided evidence that Ambidextrous Leadership has significant positive effects on both follower’s Leadership Aspiration and Job Crafting, and much of this influence is explained by the leader’s ability to cultivate a high-quality LMX relationship. Ambidextrous leaders achieve a dual impact by directly encouraging proactive behaviours, and indirectly motivating employees through strong social exchange relationships.

Discussion

This study set out to examine how Ambidextrous Leadership – a leadership style which balances exploratory and exploitative behaviours affects two important employee-level outcomes: Leadership Aspiration and Job Crafting in knowledge-based organizations. Additionally, it assessed the mediating role of LMX in these relationships. The theoretical model was supported by the analysis. Below, we discuss the findings in light of theory and prior research, the implications for practice, particularly in the Middle Eastern context, and the study’s limitations along with future research directions.

Theoretical Contributions

Our findings contribute to several streams of literature. First, we extended the scope of Ambidextrous Leadership research beyond its typical focus on innovation and performance outcomes to consider its impact on follower development (Leadership Aspiration) and proactive behaviours (Job Crafting). This suggests that the benefits of Ambidextrous Leadership are not confined to immediate task outcomes but also shape employees’ mindsets and behaviours regarding their careers and work design. The direct positive effect of Ambidextrous Leadership on Leadership Aspiration, though partially mediated, indicates that when leaders exemplify flexibility and openness, employees are likely to internalize those leadership qualities and develop greater interest in pursuing leadership roles or levels themselves. This is in alignment with role modelling and social learning principles as employees learn what it means to be a leader themselves from observing their ambidextrous leaders. It also resonates with role theory, indicating ambidextrous leaders likely expand the roles of their followers, enabling them to engage in more leadership-related activities, which can increase their aspirations.

Second, our study underscores the critical role of LMX as a mediating mechanism. In line with social exchange theory, Ambidextrous Leadership appears to foster high-quality exchanges, creating a sense of obligation and support that drives followers to go above and beyond their formal duties (e.g., craft their jobs, prepare for leadership). We answer calls for more research on “the inner mechanisms” linking paradoxical leadership styles and follower outcomes. By showing that LMX quality transmits the effects of Ambidextrous Leadership to both attitudinal and behavioural outcomes, we integrated Ambidextrous Leadership into the broader literature on relational leadership. This also confirms and expands the findings of Guo et al.’s (2020) which indicated that LMX mediates between Ambidextrous Leadership and performance/creativity– we show mediation applies to other outcomes as well. Interestingly, LMX fully mediated the effect on Leadership Aspiration, suggesting that employees mainly ramp up their aspirations when they feel in a high-quality exchange (perhaps because they then get encouragement and opportunities for leadership from the supervisors). For Job Crafting, mediation was partial; an ambidextrous leader likely signals permission to craft directly (especially via opening behaviours encouraging new approaches), in addition to the general sense of empowerment felt through LMX.

Third, we contributed to the Leadership Aspiration literature by identifying leadership style and leader-follower relationship as significant contextual factors. Prior studies on leadership aspiration have primarily focused on individual differences (e.g., gender, personality) or organizational culture (Fritz & van Knippenberg, 2018). Our results highlight that how one’s immediate leader behaves can considerably impact their ambition to pursue leadership roles which is in alignment with the study conducted by Xu, M. L. (2024) which studied how supportive leadership fosters and strengthens the leadership Aspirations. High LMX, characterized by mentorship and trust, seems to boost confidence and desire to lead, aligning with career motivation theories that emphasize developmental relationships. This integrates Leadership Aspiration with leadership and OB theories, suggesting aspiration is malleable and can be cultivated by supportive, Ambidextrous Leadership (Singh et al., 2022).

Furthermore, our study responds to calls to examine proactive work behaviours like Job Crafting in relation to leadership. While previous research showed empowering or inclusive leadership can encourage Job Crafting, we demonstrated that a nuanced style like Ambidextrous Leadership also plays a role. The positive relationship between LMX and Job Crafting reinforces that when employees feel trusted and supported (high LMX), they repay the organization by proactively improving and enhancing their current jobs. This finding aligns with the JD-R model perspective that social resources (like a supportive leader) spur crafting. We thus bridge LMX and job design literatures, suggesting high-quality leader-follower relationships enable employees to be active job crafters, which can enhance employee’s well-being and performance.

Practical Implications

The results carry several practical implications, especially for organizations operating in the Middle East’s emerging knowledge economies: Leadership Development: Organizations should consider training and developing managers in ambidextrous leadership behaviours. This means cultivating leaders’ ability to be flexible – knowing when to adopt an opening approach to stimulate innovation and when to use closing behaviours to provide structure. For example, leaders can be trained to provide their employees with an autonomous environment in problem-solving while also setting clear deadlines and standards. Our findings suggest that such balanced leadership not only improves immediate team outcomes but also builds a pipeline of future leaders (by raising aspirations) and promotes a proactive workforce (via job crafting). Companies focussed on innovation which is a key highlight in UAE’s and Saudi’s strategic plans would significantly benefit from leaders who can manage this duality. Enhancing LMX Quality: Given that LMX is a key mediator, organizations should encourage their leaders to build high-quality relationships with all their team members. This can be achieved by coaching leaders on communication, empathy, and fairness. Simple practices such as regular one-on-one meetings, offering mentorship, and recognizing good work can go a long way in improving LMX. In many Middle Eastern workplaces, leaders traditionally maintained power distance; however, our implications urge a shift toward more inclusive and supportive leader-follower relationships to fully unlock employees’ true potential. HR could implement 360-degree feedback or LMX assessments to make leaders aware of relationship quality with subordinates and set improvement goals. Career Pathing and Mentoring: To foster Leadership Aspiration, organizations (especially in knowledge sectors) should create environments where employees perceive leadership as both attainable and desirable. Ambidextrous leaders by virtue of high LMX might identify and encourage employees who show leadership interest. Formal mentoring programs can further boost this by pairing employees with senior ambidextrous leaders as role models. Given that many Gulf companies are pushing national talent into leadership (Emiratization or Saudization policies), having current leaders ignite aspiration in young professionals is valuable. Ensuring women and underrepresented groups have high-LMX relationships with their superiors could also help bridge gaps in leadership aspirations.

Promoting Job Crafting: Our findings suggest that when employees are provided support, they proactively craft their jobs. Managers can encourage job crafting by explicitly providing permissions for employees to suggest changes to their jobs or pursue projects that interest them. Workshops on job crafting or reflection exercises (e.g., having employees design their “ideal” job within organizational bounds) could be useful. Particularly in dynamic, knowledge-based roles, employees who craft their jobs often find more efficient and innovative ways to work, ultimately benefiting their organization. Leaders should thus view proactive changes not as insubordination but as positive engagement – mindset ambidextrous leaders naturally possess. Organizational systems such as flexible job descriptions or innovation time allowances (e.g., “20% time”) can institutionalize this approach. Contextual Consideration: In the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Oman, cultural norms such as respect for hierarchy and collectivism could influence how ambidextrous leadership and LMX play out. Practically, leaders in these contexts might need to carefully balance openness with the authoritative role expected of them. Our research suggests that those who manage to balance (e.g., be open to employee ideas while still respected as a guide) can achieve more favourable outcomes. Organizations in the Middle East should note that adopting some elements of Western leadership styles (empowerment, openness) does not equate to losing control. In fact, it can be integrated with traditional directive leadership to yield ambidexterity. Policymakers driving knowledge economy initiatives should invest in leadership development programs that emphasize this balance.

Limitations and Future Research

Like any study, this research has limitations that open avenues for future inquiry:

Causality and Design: We employed a two-wave survey which helps address some common method bias, but it is not a true experimental or longitudinal panel design. Reverse causality is a possibility – for example, perhaps employees who craft their jobs more could influence their leader to behave in an ambidextrous way, or high-aspiring employees might form better LMX with their supervisors. While theory guided our causal model, future studies could employ longitudinal designs with three or more waves or intervention experiments (e.g., training leaders in ambidexterity) to more definitively establish causality. An experimental vignette study might also test how participants react in terms of aspiration or crafting intentions when presented with descriptions of ambidextrous vs. non-ambidextrous leader behaviours. Single-source Data: Our data for both predictor and outcomes came from employees (albeit at different times). This raises the issue of common rater bias. We did take steps to mitigate it (time separation, assuring anonymity). However, future research could enhance the robustness of the findings by obtaining multi-source data. For instance, have leaders rate LMX from their perspective or have supervisors confirm subordinates’ job crafting behaviours. Objective career outcomes such as promotions and leadership applications could complement self-reported leadership aspiration.

Generality across Cultures: While our study context is the Middle East, the sample might not truly capture all cultural nuances of each country. We did not explicitly model cultural differences; future research could compare whether the effects of Ambidextrous Leadership differ in, say, the UAE vs. Western countries, possibly using cultural values (power distance, uncertainty avoidance) as moderators. For example, do employees in high power distance cultures respond differently to opening behaviours? Our theoretical expectation is that the positive effects hold, although their strength might vary. Including cultural orientation measures could provide valuable insights. Other Mediators and Moderators: We focused on LMX as the mediator, but other mechanisms might also be at work. For leadership aspiration, role modelling and leadership self-efficacy could mediate the influence of leader behaviour (an ambidextrous leader might increase a follower’s efficacy to lead, beyond just exchange quality). For job crafting, psychological empowerment or work engagement might be mediators. Future studies could test multiple mediators in parallel to see the unique contribution of LMX. Additionally, moderators could affect the relationships e.g., employee proactive personality might strengthen the link between LMX and job crafting (proactive individuals capitalize more on support). Gender could moderate the effect on leadership aspiration, as some literature suggests women respond more to certain cues (our model could be tested separately for male and female employees). In the Middle East, examining nationality (expatriate vs. local) might be insightful, as leadership dynamics sometimes differ for expat workers.

Ambidextrous Leadership Measurement: We treated ambidextrous leadership in a somewhat collected manner. However, some research suggests it’s the dynamic switching between opening and closing that truly defines ambidexterity. We did not capture the temporal flexibility aspect explicitly. Future research could employ the diary methods to see how leaders shift behaviours and how these shifts affect daily LMX or job crafting. Also, polynomial regression and response surface methods, as used in some congruence studies, could examine if balanced high opening & closing yields best outcomes compared to imbalance. While beyond our scope, this fine-grained approach could deepen understanding of the optimal mix of ambidexterity.

Conclusion

In summary, this study sheds light on the pivotal role of ambidextrous leadership in nurturing positive employee outcomes in knowledge-based organizations, and highlights LMX as the bridge linking leadership behaviour to employees’ aspirations and proactive behaviours. By effectively engaging in both directive and empowering leadership behaviours, ambidextrous leaders cultivate high-quality relationships that encourage employees to envision themselves as future leaders and to actively shape their own work roles. These insights are particularly salient for Middle Eastern economies in transformation, where developing human capital and innovation is paramount. Leaders who can simultaneously provide vision and flexibility will be instrumental in developing the next generation of leaders and an engaged workforce. Future research and practice should continue to explore this balancing act of leadership to unlock the full potential of employees in the evolving world of work.

References

Blau, P. M. (2017). Exchange and power in social life. Routledge.

Bodhi, R., Joshi, Y., & Singh, A. (2024). How does social media use enhance employee's well-being and advocacy behaviour? Findings from PLS-SEM and fsQCA. Acta Psychologica, 251, 104586.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Chan, K. Y., & Drasgow, F. (2001). Toward a theory of individual differences and leadership: understanding the motivation to lead. Journal of applied psychology, 86(3), 481.

Fritz, C., & van Knippenberg, D. (2018). Gender and leadership aspiration: The impact of work–life initiatives. Human Resource Management, 57(4), 855-868.

Garcia, M., & Huang, L. (2023). Mentorship and Leadership Development: How Leaders Inspire Leadership Aspirations. Leadership & Organizational Studies, 38(2), 112-128

Graen, G. B. (1976). Role-making processes within complex organizations. Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology.

Graen, G. B., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader–member exchange (LMX) theory over 25 years. The Leadership Quarterly, 6(2), 219-247.

Guo, Z., Yan, J., Wang, X., & Zhen, J. (2020). Ambidextrous leadership and employee work outcomes: a paradox theory perspective. Frontiers in psychology, 11, 1661.

Harandi, A. O., & HabibBeygi, H. (2025). A Systematic Review on Strategic renewal (A bibliometric Approach). Journal of Strategic Management Studies.

Ji, H., Zhao, X., & Wu, Q. (2023). The mediating role of job crafting between LMX and flow at work among medical workers. BMC Psychology, 11(1), 289. (Example empirical paper on LMX, job crafting, and flow)

Kristiana, Y., Sijabat, R., Sudibjo, N., & Bernarto, I. (2025). Service-oriented job crafting for employee well-being in hotel industry: a job demands-resources perspective. Cogent Business & Management, 12(1), 2463816.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Mishra, R., Rai, S., Thakur, G., & Singh, A. (2022). An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure: a study on emotional regulation, thwarted social needs, disposable income and its relationship with psychological well-being. International Journal of Work Organisation and Emotion, 13(3), 260-281.

Noesgaard, M. S., & Jørgensen, F. (2024). Building organizational commitment through cognitive and relational job crafting. European Management Journal, 42(3), 348-357.

Prinhandaka, D., Rohman, I., & Wijaya, N. (2023). Supportive leadership and employee creativity: Will Leader-Member Exchange mediate the relationship?. Annals of Management and Organization Research.

Rosing, K., Frese, M., & Bausch, A. (2011). Explaining the heterogeneity of the leadership-innovation relationship: Ambidextrous leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 22(5), 956-974.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Singh, A., & Bodhi, R. (2025). Does mindfulness moderate between incivility, aggression and conflict at work? Findings from symmetric and asymmetric modeling approaches. Acta Psychologica, 254, 104844.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Singh, A., & Waldia, N. (2024). “If you want peace avoid interpersonal conflict”: a moderating role of organizational climate. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 11(4), 892-912.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Singh, D., Singh, A., Omar, A., & Goyal, S. B. (Eds.). (2022). Business intelligence and human resource management: Concept, cases, and practical applications. CRC Press.

Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2012). Development and validation of the job crafting scale. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(1), 173-186.

Willie, M. (2025). Leader-Member Exchange and Organisational Performance: A Review of Communication, Biases, and Personality Challenges. Golden Ratio of Human Resource Management.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Wrzesniewski, A., & Dutton, J. E. (2001). Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 179-201.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Xu, M. L. (2024). A Valuable Asset in Personal and Professional Growth: How to Build a Positive Relationship with Mentors as a Mentee. ACN Journal

Zacher, H., & Rosing, K. (2015). Ambidextrous leadership and team innovation. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 36(1), 54-68. (Example of ambidextrous leadership empirical study)

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Zakiy, M. (2024). Linking Person Supervisor Fit With Employee Performance and Work Engagement: The Mediating Role of LMX. Sage Open.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Received: 12-Mar-2025, Manuscript No. AMSJ-25-15859; Editor assigned: 25-Mar-2025, PreQC No. AMSJ-25-15859(PQ); Reviewed: 28-Apr-2025, QC No. AMSJ-25-15859; Revised: 05-May-2025, Manuscript No. AMSJ-25-15859(R); Published: 31-May-2025