Research Article: 2021 Vol: 25 Issue: 5

The Moderating Effects of Typicality and the Mediating Effects of Advertising Message Involvement on Comparative Advertising

Tommy Hsu, Tarleton State University

Leona Tam, University of Technology Sydney

Citation Information: Hsu, T. & Tam, L. (2021). The moderating effects of typicality and the mediating effects of advertising message involvement on comparative advertising. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 25(5), 1-12.

Abstract

It is proposed that comparing a typical versus an atypical product attribute in advertising will distort the value of naming your competitor. Using two experimental studies, this research investigates how typicality of the product attribute influences the effectiveness of different types of comparative advertising in terms of consumer's attitude. Results from two experiments show that product attribute typicality interacted with the types of comparative advertising: direct comparative advertising was significantly more effective in changing consumers' attitude than indirect comparative advertising when a typical product attribute was compared; whereas such significant difference in effectiveness no longer held when an atypical product attribute was compared. These results were consistent regardless the compared brand was a market leader (Study 2) or not (Study 1). Finally, mediation analysis found that the product attribute typicality by comparative advertising type interaction influenced consumers' brand attitudes through the mediating role of advertising message involvement.

Keywords

Comparative Advertising, Typicality, Advertising Message Involvement.

Introduction

Comparative advertising research has progressed greatly, but results have been inconclusive and contradictory, with the majority of studies focusing on the relative effectiveness of comparative versus non-comparative advertising (Pechmann & Esteban 1993). Due to increasingly intense competition, companies have increased their use of both direct (naming their competitors) and indirect comparative advertising (Beard 2010; Miniard et al. 2006; Zhang et al. 2011). Thus, the relative effectiveness of direct and indirect comparative advertising has become a crucial topic in advertising (Pechmann & Stewart 1991; Donthu 1992; Miniard et al. 2006; Zhang et al. 2011).

Contradictory empirical findings from numerous studies means the effectiveness of direct versus indirect comparative advertising remains disputed. Thus, the main effect of either type of comparative advertising on attitude is expected to be not significant. Therefore, the effect of the independent variable (direct/indirect comparative advertising) on the dependent variable (attitude toward the brand) was evaluated based on the effects of one moderator (attribute typicality) and one mediator (advertising message involvement).

In comparative advertising, direct or indirect, the advertiser always compares itself to another company in terms of certain product attributes.

For example, in recent automobile comparative advertisements, fuel efficiency, safety, and stability are usually the focal compared points. However, are these product features compared in the advertisement perceived as important by consumers, and what are typical or atypical features that consumers think of when they think about the products? These questions relate to the concept of attribute typicality. Very little research has investigated the effect of attribute typicality, and no research of this type has been conducted in the comparative advertising context save for Pechmann & Ratneshwar (1991); Pillai & Goldsmith (2008).

Attribute Typicality as A Moderator

Product or brand attributes can be categorized on a spectrum ranging from typical to atypical (Pillai & Goldsmith 2008). Typical attributes are well-known or important functions associated with a product. When a comparative advertisement uses a typical attribute to compare, it is more likely for consumers to be involved in analyzing the comparison thoughtfully and having a piecemeal review of product attributes (Pillai & Goldsmith 2008). According to Pillai & Goldsmith (20085), “piecemeal information processing occurs when existing knowledge stored in memory is accessed to engage in a more extensive processing of a stimulus on an attribute-by-attribute basis.” Therefore, the evaluating processes will pose serious threats to consumers’ current attitudes toward both the advertised and compared brands and, thus, create counter-argumentation in their minds.

Additionally, since direct comparative advertisements engage consumers to directly associate the focal brand with the compared brand, typical attributes can not only strengthen the association but effectively differentiate the focal brand and the compared brand because typical attributes are perceived as important by consumers (Pechmann & Ratneshwar 1991). Such advertising also increases consumers’ perception of correlation between the typical attributes compared in the comparative advertisement and other attributes (Pillai & Goldsmith, 2008), and this correlation among product attributes can help them fortify their product category structure (Pechmann & Ratneshwar 1991). This structure, formed in consumers’ minds, will help them process the advertising information, especially when the comparative advertisement is direct (Barigozzi et al. 2009).

Conversely, when the attributes compared are atypical, the correlation between the advertised attribute and other attributes is weak (Pillai & Goldsmith, 2008) and consumers will have difficulty forming any category structure based on the weak correlation (Pechmann & Ratneshwar 1991). When consumers are exposed to the comparative advertisement with atypical attributes, they are likely to have less counter-argumentation than those exposed to comparative advertisement with typical attributes, so the information provided by the comparative advertisement is less threatening to the compared brands in consumers’ minds (Pechmann & Ratneshwar 1991). Consequently, the attribute atypicality will prevent consumers from processing the information in detail (Pillai & Goldsmith, 2008).

Therefore, direct comparative advertisements with atypical attributes will not be able to decrease or worsen consumers’ evaluations of the compared brands as they do when the compared attributes are typical. Indirect comparative advertisements with atypical attributes also will not be convincing when the advertisers claim they are better than every other brand as consumers do not form any association or correlation between them (Pechmann & Ratneshwar 1991).

Essentially, when consumers are exposed to either direct or indirect comparative advertisements using atypical product attributes, they will not carefully go through the attribute information provided in the advertisements and will not be influenced by what they are exposed to. Thus, the hypothesis for the moderator of attribute typicality is:

H1: Attribute typicality moderates the relationship between advertising directness and attitude toward the brand (the positive effect of direct comparative advertisements), and this is stronger when the compared attribute is atypical than when the compared attribute is typical.

In this paper, the conceptual framework includes the directness of comparative advertising (direct vs. indirect) as the independent variable and attitude toward brand as the dependent variable, while attribute typicality (typical vs. atypical) is the moderator and advertising message involvement is the mediator.

Study 1: Cell Phone Services

Cell phone service providers were used as the stimulus for this study, with T-Mobile as the advertised brand and AT&T as the competitor brand. We aimed at investigating the moderator, attribute typicality, as stated in H. A pretest was conducted to determine which attributes consumers considered typical or atypical.

Pretest

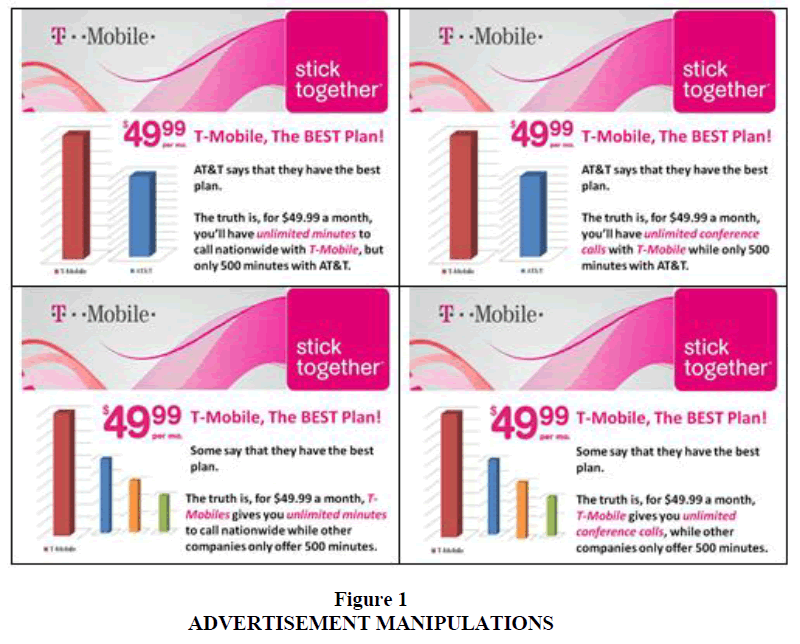

Based on cell phone plans shown on various providers’ websites, 10 different attributes for a cell phone plan were obtained. Participants were 66 undergraduate business students of a large public university in the United States (US). After being shown the 10 attributes and their descriptions, participants were asked to rank three attributes from 1 (most typical) to 3 (third-most typical) and three from 10 (least typical) to 8 (third-least typical) when they thought about cell phone service plans. From the results, we found that talking minutes was the most typical attribute (ranked most typical by 64% of participants, second-most by 6%, and third-most by 14%) and conference calling capability was the least typical one (ranked as least typical by 36% of participants, second-least by 21%, and third-least by 18%). Therefore, in Figure 1, talking minutes was used as the typical attribute and conference calling capability used as the atypical attribute.

Design and Procedure

Data were collected via Amazon Mechanical Turk. Participants were 143 adult customers in the US. The sample consisted of 81 (56.2%) female and 63 (43.8%) male participants. Respondents’ ages ranged from 20 to 66 years old with an average age of 34.4 years old and a standard deviation of 10.1. Respondents were mostly Caucasian Americans (74.2%).

An experiment was conducted with a two (advertising directness: direct vs. indirect) by two (attribute typicality: typical vs. atypical) between-subject design. Advertising directness was manipulated by whether T-Mobile specifically named AT&T (direct comparative advertising) or not (indirect comparative advertising) in the advertisement. Attribute typicality was manipulated by whether T-Mobile used a typical (talking minutes) or atypical (conference call capacity) attribute in the advertisement. In the advertisement with the typical attribute, it was stated “you’ll have unlimited minutes to call nationwide with T-Mobile,” while the advertisement with the atypical attribute stated “you’ll have unlimited conference calls with T-Mobile.”

Participants were randomly assigned into one of four experimental conditions (direct and typical, direct and atypical, indirect and typical, and indirect and atypical). First, each participant was shown the assigned advertisement and asked to read the advertisement. Then, manipulation checks questions were asked. Then, the participant responded to a series of questions regarding their attitude toward the focal brand (T-Mobile) and to provide their demographic information.

Manipulation Check

Participants were asked the degree they agreed or disagreed using a seven-point strongly disagree/agree Likert scale on two questions—“do you think T-Mobile is comparing itself to one particular competitor in the advertisement?” and “do you think the cell phone plan feature, talking minutes/conference call, T-Mobile compared in the advertisement is considered a typical one?”—for the manipulation check of advertising directness and attribute typicality respectively. For the advertising directness question, participants given direct comparative advertisements reported significantly higher (n = 66, mean = 6.756) than those given indirect comparative advertisements (n = 78, mean = 2.11) (F(1,132) = 359.89, p < .001). Additionally, participants given typical advertisements reported significantly higher (n = 73, mean = 4.99) than those given atypical advertisements (n = 71, mean = 3.0) on the attribute typicality question (F(1,132) = 44.95, p < .001). Therefore, the two manipulations in Study 1 worked as intended.

Moderating Effect of Attribute Typicality

The results of the ANOVA models showed that the main effect of advertising directness on attitude toward the brand was significant (Cronbach’s alpha = .988, F(1,132) = 11.01, p = .001). In support of H, the interaction between advertising directness and attribute typicality was significant for attitude toward the brand (F(1,132) = 6.11, p = .015).

Based on the results of the planned contrast, when the comparative advertisement was typical (coded as 1), direct comparative advertising (coded as 1) generated significantly more positive attitude toward the brand (mean = 5.43) than indirect comparative advertising (coded as 0) (mean = 4.15, F(1,132) = 14.47, p < .001). Additionally, when the comparative advertisement was atypical (coded as 0), direct comparative advertising still generated slightly more positive attitude toward the brand (mean = 4.47) than indirect comparative advertising (mean = 4.5). However, the mean difference between direct and indirect comparative advertising when an atypical attribute was used was not significant (F(1,132) = .004, p > .90).

Discussion

The results from Study 1 provide some guidelines for advertisers in terms of whether compared attributes should be typical or atypical. However, the information could be employed more effectively if a better understanding was gained on the underlying factors that influence how consumers process direct and indirect comparisons in advertisement messages. Therefore, we conducted a second study to better understand the mediating effects in the process.

Advertising Message Involvement as a Mediator

Advertising message involvement mediates the relationship between advertising messages and consumer responses or evaluations (Wang 2006; Polyorat et al. 2007). It has been investigated extensively. Eisend (2013) found that consumers with a higher level of message involvement are more likely to be affected by negative messages, while those with a lower level of message involvement are influenced by the amount of information they have received. In comparative advertising, direct comparisons have long been considered to be perceived negatively (Pechmann & Ratneshwar 1991). Therefore, it enables the advertiser to more heavily involve consumers. Conversely, indirect comparisons are generally perceived more positively (Pechmann & Ratneshwar 1991) which could have more impact on consumers with low involvement. Wang (2006) indicated that the manipulations in advertising messages work as the door attendants of message involvement which, in turn, directly affect how consumers receive and process the information (Polyorat et al. 2007). Therefore, we believe that advertising message involvement could serve as a mediator in our model.

Market Leader as the Advertised Brand

It aims at exploring a potential mediator, advertising message involvement, of the moderating effect of attribute typicality and replicating the moderating effect of attribute typicality found both in the literature and Study 1. Pechmann & Stewart (1991) found that the effects of direct comparative advertising were contingent on the relative market position of the advertised brand. In Study 1, we used a market follower, T-Mobile, as the advertiser and a market leader, AT&T, as the compared brand. Therefore, Study 2 used a market leader as the advertised brand and a market follower as the compared brand for generatability of the findings while avoiding adding overwhelming brand effect (Chang 2006, Fuchs et al. 2013).

Design and Procedure

Data were collected via Amazon Mechanical Turk. Participants were 196 adult customers in the US. The sample consisted of 102 (52%) male and 94 (48%) female participants. Respondents’ ages ranged from 18 to 71 years old with an average age of 38.2 years old and a standard deviation of 11.38. Respondents were mostly Caucasian Americans (74.8%).

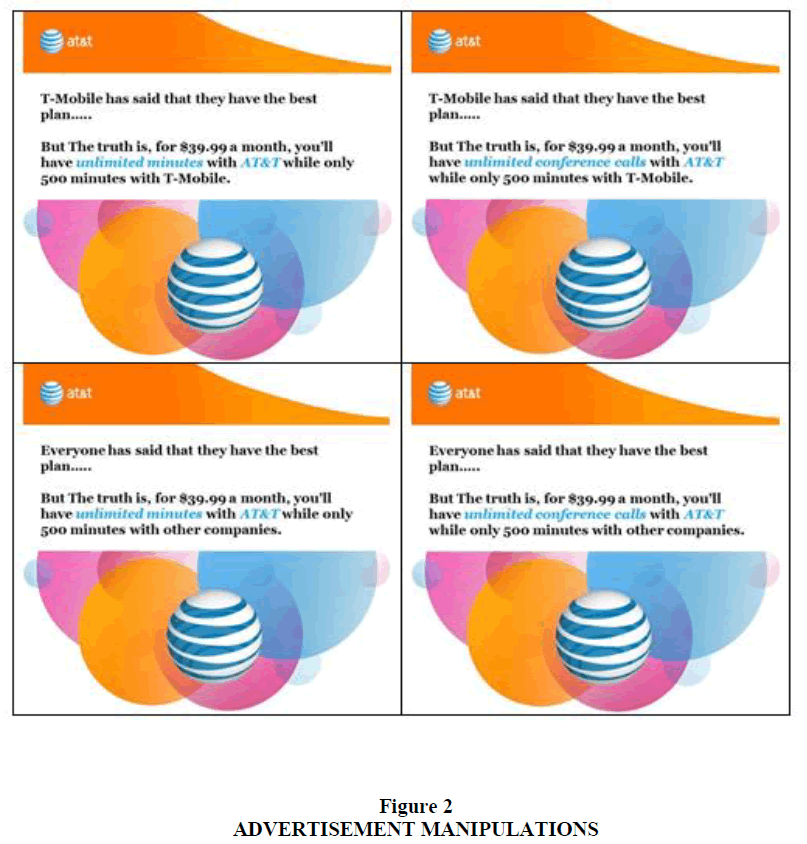

A two (advertising directness: direct vs. indirect) by two (attribute typicality: typical vs. atypical) between-subject design was used in Figure 2.

Advertising directness was manipulated by whether AT&T specifically named T-Mobile (direct comparative advertising) or not (indirect comparative advertising) in the advertisement. Attribute typicality was manipulated by whether AT&T used a typical (talking minutes) or atypical (conference calls) attribute in the advertisement. Then, participants responded to questions about their attitudes toward the brand, perceptions about their levels of involvement with the advertising messages, thoughts regarding the messages, and their demographics information. Advertising message involvement was measured using a 10-item 7-point semantic differential scale: “when looking at the ad, do you find what is advertised to be important/of concern to you/relevant/meaning a lot to you/valuable/beneficial/mattering to you/essential/significant to you/motivating” (Spielmann & Richard 2013).

Manipulation Check

Participants responded to state the level they agreed or disagreed with the following two statements using 7-point strongly disagree/agree Likert scales: “AT&T is comparing itself to one particular named competitor in the advertisement” (manipulation check of advertising directness), as well as “Unlimited conference calls/talking minutes is considered a typical feature for cell phone services” (manipulation check of attribute typicality). Participants in the direct comparative advertising conditions reported significantly higher scores (n = 94, mean = 6.60) than those in the indirect comparative advertising conditions (n = 102, mean = 1.82) on manipulation check measure (F(1,195) = 731.50, p < .001). Participants given talking minutes as the compared attribute reported significantly higher scores (n = 91, mean = 5.60) than those given conference calls (n = 105, mean = 3.39) on manipulation check measure (F(1,195) = 78.20, p < .001). Therefore, the two manipulations worked as intended.

Replicating the Moderating Effect

Consistent with Table 1, the results of the ANOVA models showed that the main effect of advertising directness on attitude toward the brand was significant (Cronbach’s alpha = .988, F(1,195) = 4.443, p = .001). Consistent with the hypothesis, the interaction between advertising directness and attribute typicality was significant for attitude toward the brand (F(1,177) = 15.28, p < .001). When the comparative advertisement was typical (coded as 1), direct comparative advertising (coded as 1) generated significantly more positive attitude toward the brand (mean = 4.58) than indirect comparative advertising (coded as 0) (mean = 3.35, F(1,177) = 28.44, p < .001). Additionally, when the comparative advertisement was atypical (coded as 0), direct comparative advertising still generated slightly more positive attitude toward the brand (mean = 4.04) than indirect comparative advertising (mean = 3.68). However, the mean difference between direct and indirect comparative advertising when an atypical attribute was used (coded as 1) was not significant (F(1,177) = 3.27, p > .07).

| Table 1 Dependent Variable: Post-Exposure Attitude | |||||

| Source | Type III Sum of Squares | Degrees of Freedom | Mean Square | F | Sig. |

| Intercept | 5.728 | 1 | 5.728 | 4.767 | .031 |

| Pre-Attitude | 114.107 | 1 | 114.107 | 94.968 | .000 |

| Age | .164 | 1 | .164 | .136 | .713 |

| Gender | .113 | 1 | .113 | .094 | .759 |

| Race | .754 | 1 | .754 | .627 | .430 |

| Direct | 13.231 | 1 | 13.231 | 11.012 | .001 |

| Typical | 1.185 | 1 | 1.185 | .987 | .322 |

| Direct * Typical | 7.342 | 1 | 7.342 | 6.110 | .015 |

| Error | 158.601 | 132 | 1.202 | ||

| Total | 3459.280 | 144 | |||

| Corrected Total | 382.729 | 143 | |||

Mediating Effect of Advertising Message Involvement

To test the mediation effects of advertising message involvement on the attitude toward the advertised brand, we closely followed the approach suggested by Zhao, Lynch, and Chen (2010) rather than the usual methodology of Baron and Kenny (1986). Zhao et al. (2010) highlighted several issues with Baron and Kenny’s (1986) procedure and suggested a revised testing approach that provides a more nuanced analysis of mediation effects. Zhao et al. (2010) recommend replacing the Baron–Kenny “three tests + Sobel” approach with a single bootstrap test of the indirect (mediated) effect (which is the multiplicative product of the path from the independent variable to the mediator and the one from the mediator to the dependent variable (Preacher & Hayes 2008); see Zhao et al. (2010) for detailed discussion).

Discussion

The results indicated that the mean indirect effect for advertising message involvement from the bootstrap analysis was positive and significant (.0544), with a 95% confidence interval that did not include zero (.0996 ~ .3150). In the indirect path, a change from indirect comparative advertising to direct comparative advertising increased advertising message involvement by .533 units on the one-to-seven scale. Holding advertising directness constant, a unit increase in advertising message involvement increased the attitude toward the advertised brand by .357. However, the direct effect (–.0098) of advertising directness on the attitude toward the advertised brand was not significant (p = .923). Thus, we concluded that advertising message involvement is an indirect-only mediator for the relationship between advertising directness and attitude toward the advertised brand. Building on Zhao et al. (2010), our results provide evidence that the mediator is consistent with the hypothesized theoretical framework and it is unlikely there is any omitted mediator.

A conceptual framework was developed in this paper to address the research gap on direct versus indirect comparative advertising and investigate the effects of one moderator and one mediator that could help explain the mixed results in previous research. Two studies were conducted based on this framework, and both provide invaluable insights for understanding the effectiveness of direct versus indirect comparative advertising, particularly with respect to different formats of comparative advertisements regarding attributes compared. As hypothesized, in Study 1, it was found that when the compared attribute was typical, direct comparative advertisements generated more positive attitude toward brand than indirect comparative advertisements. When the compared attribute was atypical, there was no difference in attitude toward the brand and purchase intention generated by direct and indirect comparative advertisements. The results from Study 2 indicate that comparison type is irrelevant when an atypical attribute is used in the advertisement, supporting the earlier findings of Pillai and Goldsmith (2008).

In Table 2, the results of the mediation analysis indicate that a change from indirect comparative advertising to direct comparative advertising increases advertising message involvement which improves the attitude toward the advertised brand. Thus, direct comparative advertisements are significantly better than indirect comparative advertisements in enhancing consumers’ involvement with advertising messages and, in turn, increasing the consumer’s attitude toward the advertised brand. This indirect-only mediating effect provides another explanation for the inconclusive findings among previous studies on the relationship between advertising directness and consumer responses. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first research specifically focused on the mediating effect of advertising message involvement on the effectiveness of comparative advertising. We hope this research can advance existing knowledge but also initiate a new research stream in comparative advertising research.

| Table 2 Anova Results of Study 2 | |||||

| Dependent Variable: Post-Exposure Attitude | |||||

| Source | Type III Sum of Squares | Degrees of Freedom | Mean Square | F | Sig. |

| Intercept | 1.029 | 1 | 1.029 | 1.144 | .286 |

| Involve_AVG | .439 | 1 | .439 | .489 | .485 |

| Pre_Att_AVG | 59.236 | 1 | 59.236 | 65.893 | .000 |

| Age | .186 | 1 | .186 | .207 | .649 |

| Gender | .017 | 1 | .017 | .019 | .890 |

| Race | 3.020 | 1 | 3.020 | 3.360 | .068 |

| Direct | 27.111 | 1 | 27.111 | 30.158 | .000 |

| Typical | .038 | 1 | .038 | .042 | .838 |

| Direct*Typical | 13.738 | 1 | 13.738 | 15.282 | .000 |

| Error | 159.118 | 177 | .899 | ||

| Total | 3377.760 | 194 | |||

| Corrected Total | 459.689 | 193 | |||

This paper also has managerial implications and applications. First, the results inform us that companies using direct comparisons must, to ensure the effectiveness of their advertisements, identify the attributes typically considered by consumers when they make purchasing decisions. Presently, we see more direct comparative advertisements, such as Apple versus Samsung or Coke versus Pepsi, with most companies directly competing in multiple countries and markets. This issue can become even more critical when a company is targeting multiple market segments as typical attributes may be different across different market segments.

Conclusion

Although this paper provides useful and meaningful insights and managerial implications, there are some limitations. First, this research does not consider the different levels of “directness” of comparative advertising. In practice, different comparison strategies have been used by companies. For example, some companies only show competitors’ logos or brand names in their direct comparative advertisements without naming them in the messages. Some companies included competitors’ slogans in their messages to imply who they are referring to (e.g., Esurance, an Allstate company, states “15 minutes can save you 15% of car insurance” in the advertisements to imply comparison with Geico). In both examples, consumers potentially know the particular competitor the advertiser is referring and comparing to. Additionally, it cannot be assumed that consumers perceive “the leading brand” and “other brands” identically. This research only uses “other brands” and “everyone else” in the manipulations of indirect comparative advertisements.

Generalizability is a concern for both studies in this paper. The conclusions of each study are based on findings from a research setting and one product. No additional studies were done to generalize the findings.

Additionally, both studies use products generally considered as utilitarian products (cell phone services). Therefore, no hedonic products or attributes are considered in this paper.

References

- Barigozzi, Francesca, Paolo G. Garella, and Martin Peitz (2009), "With a Little Help from My Enemy: Comparative Advertising as a Signal of Quality," Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 18 (4), 1071-94.

- Barry, Thomas E. (1993). “Comparative Advertising: What Have We Learned in Two Decades?”. Journal of Advertising Research, March/April, 19-29.

- Beard, Fred & Chad Nye (2010). “Caught In The Middle: A History Of The Media Industry's Self-Regulation Of Comparative Advertising”, American Academy of Advertising Conference Proceedings, 52-53.

- Chang, Angela Chiu-Chi and Kukar-Kinney, Monika (2007), “The impact of a pioneer brand on competition among later entrants,” Journal of Customer Behaviour, 6(2), 195-210.

- Chang, Chingching (2007). “The Relative Effectiveness of Comparative and Noncomparative Advertising: Evidence For Gender Differences in Information-Processing Strategies”, Journal of Advertising, 36(1), 26-35.

- Donthu, Naveen (1992), "Comparative Advertising Intensity," Journal of Advertising Research, 32 (6), 53-58.

- Eisend, Martin (2013), “The Moderating Influence of Involvement on Two-Sided Advertising Effects”, Psychology and Marketing, 30(7), 566–575.

- Gentner, Dedre & Arthur B. Markman (1994), "STRUCTURAL ALIGNMENT IN COMPARISON: No Difference Without Similarity," Psychological Science (Wiley-Blackwell), 5 (3), 152-58.

- Grewal, Dhruv, Sukumar Kavanoor, Edward F Fern, Carolyn Costley, and James Barnes (1997). “Comparative versus noncomparative advertising: A meta-analysis”, Journal of Marketing, 61(4), 1-15.

- Jeon, Jung Ok and Sharon E. Beatty (2002), "Comparative advertising effectiveness in different national cultures," Journal of Business Research, 55(11), 907-13.

- Mazodier, Marc, Armando Maria Corsi, and Pascale G. Quester (2018). “Advertisement Typicality: A Longitudinal Experiment”, Journal of Advertising Research, 58(3), 268-281.

- Miniard, Paul W., Michael J. Barone, Randall L. Rose, & Kenneth C. Manning (2006). “A Future Assessment of Indirect Comparative Advertising Claims of Superiority Over All Competitors”, Journal of Advertising, 35(4), 53–64.

- Na, WoonBong, Youngseok Son, & Roger Marshall (2006), "The Structural Effect of Indirect Comparative Advertisements on Consumer Attitude, When Moderated by Message Type and Number of Claims," in Advances in Consumer Research - Asia-Pacific Conference Proceedings.

- Pechmann, Cornelia & David W. Stewart (1990). “The Effects of Comparative Advertising on Attention, Memory, and Purchase Intentions”, Journal of Consumer Research, 17, 180-191.

- Pechmann, Cornelia & David W. Stewart (1991). “How Direct Comparative Ads and Market Share Affect Brand Choice”, Journal of Advertising Research, 47-55.

- Pechmann, Cornelia & S. Ratneshwar (1991). “The Use of Comparative Advertising for Brand Positioning: Association versus Differentiation”, Journal of Consumer Research, 18(2), 145-160.

- Pechmann, Cornelia & Gabriel Esteban (1993), "Persuasion Processes Associated With Direct Comparative and Noncomparative Advertising and Implications for Advertising Effectiveness," Journal of Consumer Psychology (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates), 2 (4), 403.

- Pillai, Kishore G. & Ronald E. Goldsmith (2008). “How brand attribute typicality and consumer commitment moderate the influence of comparative advertising”, Journal of Business Research, 61(2008), 933–941.

- Polyorat, Kawpong, Dana L. Alden, Eugene S. Kim (2007), “Impact of Narrative versus Factual Print Ad Copy on Product Evaluation: The Mediating Role of Ad Message Involvement”, Psychology & Marketing, 24(6), 539–554.

- Priester, Joseph R., John Godek, D.J. Nayakankuppum, & Kiwan Park (2004), "Brand Congruity and Comparative Advertising: When and Why Comparative Advertisements Lead to Greater Elaboration," Journal of Consumer Psychology (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates), 14 (1/2), 115-23.

- Schwaiger, Manfred, Carsten Rennhak, Charles R. Taylor, & Hugh M. Cannon (2007), "Can Comparative Advertising Be Effective in Germany? A Tale of Two Campaigns," Journal of Advertising Research, 47 (1), 2-13.

- Shao, Alan T., Yeqing Bao, & Elizabeth Gray (2004), "Comparative Advertising Effectiveness: A Cross-Cultural Study," Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising (CTC Press), 26 (2), 67-80.

- Snyder, Rita (1992), "Comparative Advertising and Brand Evaluation: Toward Developing a Categorization Approach," Journal of Consumer Psychology (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates), 1 (1), 15.

- Spielmann, Nathalie & Marie-Odile Richard (2013), “How Captive Is Your Audience? Defining Overall Advertising Involvement”, Journal of Business Research, 66, 499–505.

- Wang, Alex (2006), “Advertising Engagement: A Driver of Message Involvement on Message Effects”, Journal of Advertising Research, December, 355-368.

- Wilkie, William L. & Paul W. Farris (1975), "Comparison Advertising: Problems and Potential," Journal of Marketing, 39 (4), 7-15.

- Yang, Xiaojing, Shailendra Jain, Charles Lindsey, & Frank Kardes (2007), "Perceived Variability, Category Size, and the Relative Effectiveness of "Leading Brand" Versus "Best in Class" Comparative Advertising Claims," Advances in Consumer Research, 34, 209-09.

- Zhang, Lin, Melissa Moore, & Robert Moore (2011), "The Effect of Self-Construal on the Effectiveness of Comparative Advertising," Marketing Management Journal, 21 (1), 195-206.