Research Article: 2025 Vol: 29 Issue: 6

The Psychological Toll of Uncertainty on Ngo Staff: Proposing The Policy Frameworks

Walter Mwasaa, Rushford Business School, Switzerland

Citation Information: Mwasaa, W. (2025) The psychological toll of uncertainty on ngo staff: proposing the policy frameworks. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 29(6), 1-17.

Abstract

Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are important in global community development, humanitarian aid, and social justice, often working in volatile spaces characterized by uncertainties. This study critically examines three primary uncertainties—financial constraint, infrastructural limitation, and human resource challenges—highlighting their psychological impact on NGO staff. Drawing exclusively from peer-reviewed articles from the past decade, this research synthesizes theoretical and empirical insights to reveal the effect of these interconnected forms of organizational uncertainty on mental health outcomes like anxiety, burnout, and stress among NGO staff. The analysis is supported by key theoretical frameworks: the Effort–Reward Imbalance (ERI) Model, the Job Demand–Control–Support (JDCS) Model, and the Conservation of Resources (COR) Theory. The objective of the study is twofold: to systematically review relevant articles following inclusion and exclusion criteria and to propose evidence-based policy frameworks for mitigation. A secondary qualitative method approach is used in the study wherein a systematic literature review (SLR) for qualitative information and secondary data from authentic sources is integrated to draw insightful findings. Data from authentic sources revealed that global NGO funding in 2025 covered only 5.2% of needs, with over 60% from three major donors, heightening vulnerability. Workforce trends revealed 3.1% annual growth in total staff, but the vacancy rate was found to be 11%, suggesting issues related to human resource uncertainty. Regional variations are evident, with acute challenges in Africa and South Asia compared to Europe. These trends, coupled with thematic analysis, provide an essential background to comprehend the holistic picture of NGOs' vulnerabilities. The proposed policy framework is based on interconnected strategies, financial reserves, and diversification for budget stabilization; investment in infrastructure and digital training to reduce isolation; HR reform for capacity building and stable contracts; and an integrated mental health support system. In summary, this study fills in knowledge gaps about the psychological effects of uncertainty and promotes systemic changes to improve staff resilience and NGO sustainability. To improve these frameworks, future studies should investigate culturally specific models and longitudinal interventions.

Keywords

NGO, Financial Constraints, NGOs, Mental Health, Psychological Impact, Human Resources, Infrastructure.

Introduction

Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) are indispensable actors in global social welfare, humanitarian response, and social development, often functioning in states with limited capacity. Their scope of work extends to direct service delivery in education, healthcare, promotion of social justice, disaster relief, and research. As their scope expands, NGO staff are exposed to challenging factors, precipitating a psychological toll that is rarely addressed in formal policies (Ager et al., 2012). Though the need for mental health support in NGOs is acknowledged in many studies (Lopes Cardozo et al., 2013; Khudaniya & Kaji, 2014), the sector continues to focus on physical well-being and programmatic yield over staff psychological resilience.

A crucial but underexplored area of NGOs is the risk of uncertainty, particularly financial instability, human resource vulnerabilities, and infrastructural limitations. Financial instability is an almost-constant characteristic of NGO operations, closely tied to changing funding priorities, fluctuating donor interest, and irregular availability of grants (Tugyetwena, 2023). For NGO staff, financial uncertainty results in limited career advancement, inconsistent program delivery, job insecurity, and elevated anxiety regarding the sustainability of efforts and employment continuity (Gilstrap et al., 2019). Many studies have revealed that fiscal volatility is directly correlated with stress, risk of depression, and emotional exhaustion among NGO staff, particularly in the development and healthcare sectors that depend on high-stakes funding (Ali, 2016; Jachens et al., 2019).

The Effort-Reward Imbalance (ERI) model (Siegrist, 1996) offers important explanations for this dynamic, revealing that when high occupational inputs are not balanced with financial or symbolic compensation, workers experience increased psychological strain, a framework that supports the reports of burnout in underfunded NGOs (Navajas-Romero et al., 2020). Infrastructure limitations like communication breakdown, inadequate access to office space, and poor transportation systems result in structural uncertainty. This is prominent in field-based NGOs working in conflict-affected or remote areas, wherein the ability to deliver services is impeded by logistical constraints, resulting in operational inefficiencies (Malhouni & Mabrouki, 2024). Infrastructural uncertainty can be linked to Karasek’s Job Demand-Control-Support (JDCS) model states that high demand with minimal control results in heightened occupational stress (Van der Doef & Maes, 2019). The uncertainty related to human resource challenges further compounds the issue.

The aim of this study is to critically examine the psychological impact of uncertainty, related to financial constraints, infrastructure issues, and human resource challenges, on staff working in NGOs. Drawing exclusively from peer-reviewed articles from the past decade, this research synthesizes theoretical and empirical insights to reveal the effect of these interconnected forms of organizational uncertainty on mental health outcomes like anxiety, burnout, and stress among NGO staff. The primary goal of the research is to develop an evidence-based policy framework that can support stakeholders in addressing the risks, improving staff resilience, and sustaining performance in a volatile space.

Literature Review

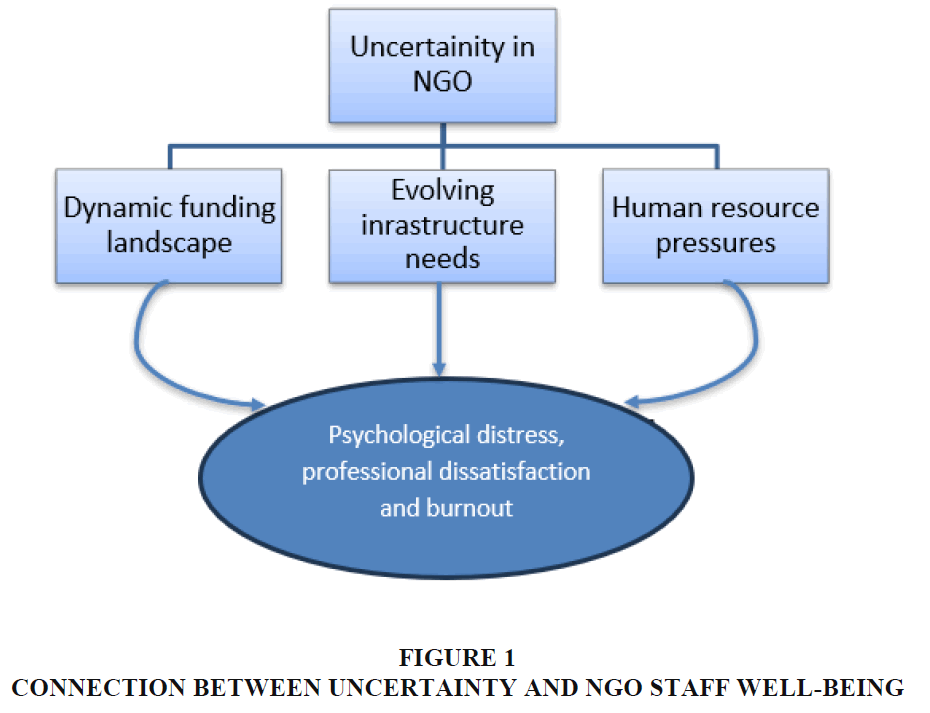

Uncertainty has become a defining characteristic of the work of NGO staff globally, governed by evolving infrastructural needs, a changing funding landscape, and managing human resource pressures. These domains result in operational challenges and synergistically interact to result in professional dissatisfaction, psychological distress, and burnout, as shown in Figure 1.

Financial Constraints: Structural Funding Barriers

A recurring theme in literature is the “unpredictability of funding streams” for NGOs. Kermani and Reandi (2023) leveraged practical case analysis from rural Malawi and revealed that funding scarcity and volatility are major chronic stressors for small NGOs. It limits project sustainability and results in stress and staff layoffs. Batti (2014) throws light on the endemic challenges associated with resource mobilization in local African NGOs, revealing weak donor connections, strict funding parameters, and limited capacity in proposal writing.

Karanth (2018) presents a conceptual analysis in which the misalignment between the project lifespan and donor funding cycle is attributed to being the major reason behind the imbalance in cash flow. The cyclical shortfall jeopardized the organizational continuity, and it also increased anxiety among leadership and staff about job security (Tugyetwena, 2023).

Ali and Gull (2016) and Ali (2016) presented a subtle perspective on government funding, highlighting its double-edged sword nature. Public grants help in creating financial stability, but excessive reliance can result in politicization, mission drift, and uncertainty if priorities of the government change or compliance requirements are updated. Their study takes into account case data and surveys from Pakistan and the Northern Territory of Australia, revealing the absence of participative funding practices and staff concern about short-termism.

A comparative study by Cunningham et al. (2014) shows the effect of government funding models in Canada and Australia on employment in the non-profit sector. The risk of short-term employment and contractualization increases staff insecurity. The findings aligned with the theoretical framework of both Effort–Reward Imbalance (ERI) and Job Demand–Control–Support (JDCS) models, as the former model connects work imbalance and insufficient compensation with adverse mental health and burnout, and the latter model explains stress as an outcome of high job demand and insufficient support.

Psychological Toll of Funding Volatility

Jachens et al. (2019) supported the ERI model in the humanitarian sector, suggesting a strong relationship between effort-reward impact and burnout in social workers. The findings of their study confirm that when organizational resources like reward and security fail to match the efforts and risks undertaken by the workers, it results in a proliferation of adverse mental health outcomes. Further study by Navajas-Romero et al. (2020) extended to well-resourced developed areas, showing that even when basic financial stability is achieved, psychological well-being is still sabotaged by structural uncertainties, limited staff support, and shifting performance expectations. It implies that the perception of uncertainty, rather than just financial stability, usually determines staff mental stress and burnout risk. Tugyetwena (2023) explored the interrelation between funding strategy, governance, and sustainability. It concluded that weak governance can increase the destabilization impact of uncertain funding and eventually impact staff morale and retention.

Infrastructure Limitations: Logistical and Technological Barriers

Malhouni and Mabrouki (2024) focused on conflict-affected contexts (the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and the Central African Republic (CAR)). They present rare field-driven evidence suggesting that a lack of foundational infrastructure, like transport and digital communication, complicates humanitarian logistics, also impacting the working environment and psychological safety of workers. Insecurity in field access, support shortfall, and delays result in operational breakdown and heightened occupational stress. Similarly, Batti (2014) and Kermani & Reandi (2023) highlight that infrastructural limitations in rural NGOs are a major roadblock to donor engagement, beneficiary outreach, and staff retention, showing the compounding effect of financial and infrastructure deficiencies.

Digital Divide and Organizational Stress

Digital transformation across sectors was largely accelerated as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, but Mikolajczak et al. (2022) state that many NGOs, particularly outside urban centers, were crippled by poor internet access, lack of digital literacy, and insufficient technology. This resulted in fragmented teamwork, increased feelings of professional isolation, and reduced access to mental health support, specifically during peak crisis times.

Human Resource Challenges: Staffing Precarity and Employment Conditions

Cunningham et al. (2014) and Bhui et al. (2016) outline an increase in short-term, project-related contractual employment in the non-profit sector, driven by market-oriented updates and funder preference, in line with the JDCS model. This employment trend declines job security, results in responsibility overload, and reduces staff’s perceived control over their role, all core components for psychological distress. Furthermore, Batti (2014) and Kermani & Reandi (2023) highlight the dual challenge of retaining skilled workers and managing heavy workloads with limited funding, which usually triggers skill drain and high turnover. Ali (2016) observed that organizational instability, connected to inconsistent government funding, discourages skilled mental health professionals from staying in NGO-related workspaces.

Mental Health Outcomes and Stigma

Khudaniya & Kaji (2014) and Bhui et al. (2016) found that NGO staff, similar to government and corporate sector staff, report increased job dissatisfaction and occupational stress. Qualitative interview data were analyzed to find that workload and lack of clarity of responsibilities increase the risk of anxiety and depression. Further, the stigma associated with mental health is a major hurdle, as highlighted by Bharadwaj et al. (2017), stating that employees in many NGOs are hesitant to talk about psychological stress because of the fear of judgment and professional repercussions. This results in a culture wherein psychological distress is unacknowledged and unaddressed, further worsening staff withdrawal and mental health decline. The primary qualitative study conducted by Castanheira (2024) explored the effectiveness of mental health support strategies in the humanitarian sector. The findings emphasize the lack of organization-wide systematic psychosocial intervention and dependence on ad hoc coping practices. It was found that NGOs with strong psychosocial support had higher morale, enhanced perception of inclusivity, and lower rates of burnout.

COVID-19 and New Stressors

Mikolajczak et al. (2022) and Begum et al. (2024) studied the impact of the pandemic and reported that there was an increase in work-related stress and ambiguity in roles because staff moved to emergency response or remote modalities under resource limitations. Begum et al. (2024) found that in Bangladesh, a significant rise in stress, depressive, and anxiety symptoms among NGO staff was observed, wherein lack of institutional support and limited coping resources further increased the risk.

International directors experience cross-cultural stressors and high-stakes decision-making in resource-constrained environments where coping strategies range from peer support to disengagement, wherein the latter might increase the risk of reduced commitment and resignation (Gilstrap et al., 2019).

Integrative Theoretical Analysis: Effort-Reward Imbalance (ERI) Model

The ERI model given by Siegrist (1996) states that work imbalance and insufficient reward are connected with employee burnout and adverse mental health conditions. Multiple studies (Ali, 2016; Jachens et al., 2019; Bhui et al., 2016) support this model, revealing that NGO workers face high expectations but are provided limited financial, reputational, or social reward. This imbalance is further increased because of structural funding gaps and donor reliance, resulting in absenteeism, emotional stress, and retention challenges.

Job Demand-Control-Support (JDCS) Model

Karasek & Theorell in 1990 gave this model to explain that stress is a consequence of high job demand, insufficient support, and low control. Studies by Cunningham et al. (2014), Bhui et al. (2016), and Navajas-Romero et al. (2020) provide empirical evidence for this framework. High job demands related to output targets, deadlines, and multitasking; low control, like role ambiguity and inflexible contracts; and insufficient support interact to heighten the psychosocial risks.

Conservation of Resources (COR) Theory

Hobfall et al. (2018) believe that psychological stress is the outcome of threatening or losing valuable resources (psychological or tangible), and when gains are limited. This theory is echoed in studies by Malhouni & Mabrouki (2024) and Begum et al. (2024) arguing that stress is the outcome of threat or loss of valuable resources, be they financial (benefits, salary), human (mental health services, support staff), or infrastructural (stable premises, tools). Resource loss spirals are evident during times of crisis, acute funding cuts, or sectoral reform, triggering a compounded psychological impact.

Regional Variations and Organizational Response Developed vs. Developing context

Research reminds us that even well-funded NGOs in developed countries are not immune to mental health risks, particularly during the pressure of innovation, digitalization, and diversification of funding sources (Navajas-Romero et al., 2020). In China, Yao et al. (2025) discussed uncertainty in roles, insufficient funding security, unclear policy direction, and organizational capacity limitations in NGOs. However, the situation is comparatively worse in lower-income, less institutionalized developing contexts (Kermani & Reandi, 2023; Batti, 2014; Malhouni & Mabrouki, 2024). Operational risk is more acute in such NGOs due to weaker HR pipelines, funding volatility, and lack of infrastructure, as a result of which adverse health of staff is more likely.

Coping Strategies and Policy Gaps

Coping mechanisms identified from a review of literature include the development of peer support groups, rotational workloads, and external counseling access (Gilstrap et al., 2019; Castanheira, 2024). But these mechanisms remain highly informal and scattered unless made mandatory by the organization. Few articles (Castanheira, 2024; Navajas-Romero et al., 2020) reveal evidence of large-scale and systematically incorporated mental health support practices within the sector.

Synthesis: Key Patterns and Research Gaps

The systematic review of literature established that uncertainty, in terms of finance, infrastructure, and human resources, directly or indirectly affects NGO staff’s mental health, satisfaction, and NGO sustainability. The theoretical frameworks like ERI, JDCS, and COR provide strong explanatory support, but the majority of the interventions remain context-dependent and isolated. The need for data-driven and integrated policy responses was further highlighted during the pandemic. The required policy would acknowledge various stressors faced by NGO staff, specifically the intersection of funding, infrastructure, and human resources.

Further, the gap in literature is significant in terms of longitudinal research, quantitative mental health metrics, and rigorous evaluation of psychosocial interventions. Comparing context, systematizing policy framework, and incorporating mental health in HR strategy and governance is the need of the hour for sectoral reforms Table 1.

| Table 1 Summary of SLR | ||||

| Author(s) and year | Region/Context | Methodology | Findings/Focus | Theoretical lens |

| Cunningham et al., 2014 | Canada, Australia | Survey/Comparative | Government funding impacts employment, increasing precarity. | ERI, JDCS |

| Batti, 2014 | Africa (General) | Case study/Survey | Local NGOs face hurdles in resource mobilization, infrastructure, and HR barriers. | COR |

| Khudaniya & Kaji, 2014 | India | Quantitative | NGO staff stress linked to job satisfaction | JDCS |

| Ali & Gull, 2016 | Pakistan | Mixed Method | Government funds provide security but can shift priorities, politicize, and increase uncertainty. | ERI, JDCS |

| Ali, 2016 | Australia | Case study | Government funding fluctuations impact the mental health of NGO staff. | ERI |

| Bhui et al., 2016 | UK | Qualitative Survey | Stigma around mental health and the issue of misaligned interventions | ERI, JDCS, COR |

| Zupancic & Pahor, 2016 | Slovenia | Qualitative stakeholder analysis | Highlighted resource constraints, role ambiguity, and unstable funding as core uncertainties. | COR |

| Bharadwaj et al., 2017 | International | Literature/Survey | Stigma discourages mental health disclosure and support usage. | COR |

| Karanth, 2018 | Conceptual/India | Framework Analysis | Donor cycle misaligned with project requirement, resulting in cash flow gaps and staff anxiety. | ERI, COR |

| Hobfoll et al., 2018 | Review/Global organizational studies | Conceptual Review | COR theory explains how stress arises from actual or threatened loss of valued resources at work. | COR |

| Jachens et al., 2019 | International | Quantitative Survey | ERI connected to burnout in aid workers | ERI |

| Gilstrap et al., 2019 | International Directors | Qualitative | Coping with operational, resource, and cross-cultural stressors | JDCS, COR |

| Navajas-Romero et al., 2020 | Developed EU | Quantitative Survey | Even resource-rich NGOs have uncertainty and workplace stress | JDCS |

| Mikolajczak et al., 2022 | Europe/Emerging Markets | Case/Survey Review | COVID-19 increased funding and technology challenges, and declining NGO working conditions | JDCS, COR |

| Kermani & Reandi, 2023 | Malawi | Case Study | Small NGOs struggle with funding, staff strain, and limited infrastructure. | JDCS, COR |

| Tugyetwena, 2023 | International (Literature Review) | Synthesis | Link between governance and funding strategy: instability results in unsustainability. | ERI, COR |

| Massazza et al., 2023 | Global | Scoping Review | Reviewed 101 studies linking uncertainty, like job, economic, and political uncertainty, with mental health, like stress, anxiety, and depression. | COR |

| Castanheira, 2024 | Humanitarian Field | Qualitative/Thesis | Systematic mental health support is valuable but rarely practiced. | ERI, JDCS, COR |

| Malhouni & Mabrouki, 2024 | DRC, CAR | Fieldwork | Workforce risk, infrastructure/logistical challenges | JDCS, COR |

| Begum et al., 2024 | Bangladesh | Mixed Methods | COVID-19 increases stress and anxiety; limited coping in NGO staff | COR |

| Yao et al., 2025 | Shanghai, China | Qualitative interviews, thematic analysis | NGO leaders revealed uncertainty in their role, funding insecurity, and organizational capacity limitations. | COR |

Methodology

Study Design

This research uses a secondary qualitative approach, including thematic analysis, to extensively understand the psychological impact of uncertainty on NGO staff. For the qualitative part, a systematic literature review (SLR) approach, particularly focusing on financial constraints, infrastructure limitations, and human resource issues, is adopted. To ensure rigor, transparency, and reproducibility, SLR strictly follows the established protocols and incorporates PRISMA for guiding the review process. For the quantitative part of the study, secondary data from reputable government websites, large-scale surveys, and databases will be used to draw descriptive inferences.

Eligibility Criteria: Inclusion Criteria

• Peer-reviewed journal articles, dissertations, policy briefs, and conference proceedings from 2014 to 2025

• Research providing empirical detail on psychological outcomes from three core uncertainties

• Studies related to local and international NGOs in the social, health, and humanitarian sectors

Exclusion criteria:

• Articles without peer review, editorials, or commentaries without authentic data

• Study outside the defined sectoral (NGO-related studies) focus and period.

Data Sources and Search Strategy

The initial search was focused on scholarly databases (PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science) and sector-specific sources like humanitarian and nonprofit organization journals. The search was performed using a combination of targeted keywords like “NGO” AND “financial constraints,” “NGOs” AND “mental health” OR “psychological impact,” “human resource,” and “infrastructure.” Reference management software (EndNote) was used to collate and perform initial screening of the articles. The eligibility of each source was checked through sequential review of the title, abstract, and full text as per the inclusion criteria discussed.

Study Selection Process

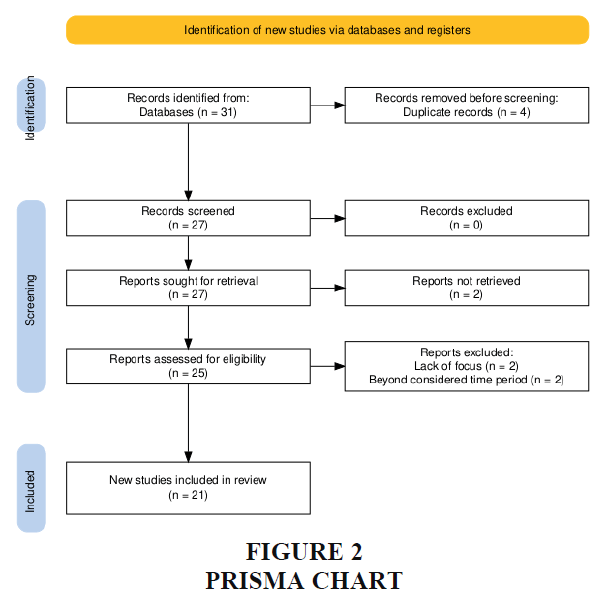

The article selection process followed four major steps as per the PRISMA structure shown in Figure 2. In the identification stage, all the potentially relevant articles (31 articles) from PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar were compiled and cross-checked. In the initial screening, 4 articles were removed because of duplicates.

The abstracts of the remaining 27 articles were screened, and an attempt was made to access the full text. 2 articles were removed because of access issues, 25 articles were then checked, and because of a lack of focus or being beyond the considered time period, 4 articles were removed, and eventually 21 articles were selected for SLR.

Secondary Data Analysis

For quantitative analysis, secondary data from national government statistics, annual reports on NGOs, and databases managed by the United Nations, the International Labor Organization (ILO), and the World Bank were considered. To ensure the integrity of data and cross-country comparison, secondary data from only reputable and verified sources was collected. The data selection focused on NGO funding level, year-to-year variability, human resource indicators, infrastructure access, and quantitative reports on psychological health. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize trends in secondary data and visualize relationships between study parameters in a tabular format. Since the secondary data sources were all publicly accessible, the need for formal ethical approval was eliminated. Considering heterogeneity in the research design, a narrative synthesis approach was used. Thematic analysis was used to group according to three core uncertainties and psychological outcomes. Specific focus was given to theoretical frameworks across different selected studies.

Findings

Qualitative Findings: Financial Constraints: Instability, Government Funding, and Psychological Risk

Financial instability has emerged as a persistent factor in NGO operations across diverse regional settings. Local NGOs across Africa and in Malawi cite issues like the unpredictability of grant cycles and donor volatility as major stressors that jeopardize staff livelihoods and project sustainability (Batti, 2014; Kermani & Reandi, 2023). Interview data and other similar studies reveal that sudden interruptions in funding result in unpaid work, salary delay, and job insecurity (Cunningham et al., 2014; Ali & Gull, 2016).

Government funding is described as a mixed perk; it provides temporary stability but has the risk of compliance hurdles, sudden shifts in resources, and politically driven challenges (Ali, 2016; Tugyetwena, 2023). In such an environment, staff experience emotional stress and professional detachment because efforts hardly lead to sustained rewards, thus aligning with the tenets of the ERI model.

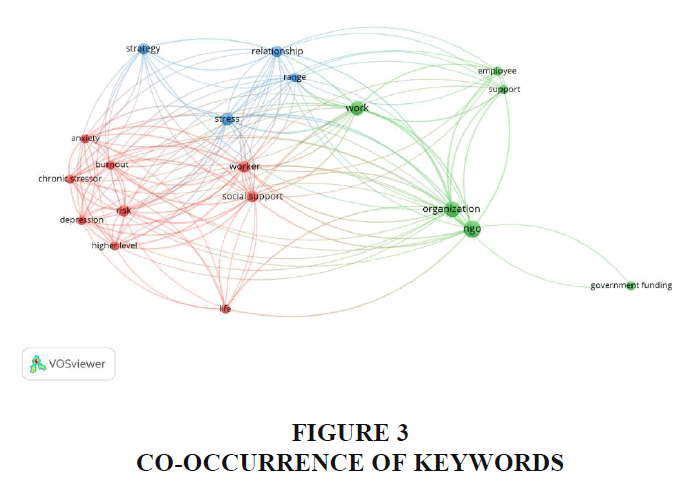

The selected articles were analyzed on VOSviewer. The co-occurrence of keywords, as shown in Figure 3, revealed dominant keywords like worker, stress, and chronic stressor. The map also reveals government funding and support, which emphasizes the connection between these tressors and psychological impacts like anxiety and depression.

The psychological toll is tangible; workers who face funding issues report a higher risk of absenteeism, withdrawal, and burnout, more so as distress is compounded over repeated funding issues (Navajas-Romero et al., 2020).

Infrastructure Limitations: Logistical Gaps and Occupational Strain

Many NGOs, specifically in low-income areas, struggle with major infrastructure deficits, including scarce digital tools, unreliable transport, and inadequate space. The limitation affects daily operational efficiency and service delivery effectiveness (Malhouni & Mabrouki, 2024; Kermani & Reandi, 2023). Qualitative data further reveals that NGO staff in such spaces feel professionally unsupported and isolated, an issue that became serious during the pandemic (Mikolajczak et al., 2022). The digital divide intensifies role ambiguity and stress, especially when there is a lack of technological support to opt for a hybrid or remote model (Begum et al., 2024). The gap in infrastructure reduces collective morale and worsens emotional fatigue.

Human Resource Challenges: Burnout, Turnover, and Stigma

Job precarity and high staff turnover are unavoidable in NGOs facing uncertainty. High workload but low salary pushes away skilled staff; NGOs are left with new recruits or contractual volunteers with limited knowledge of the field (Cunningham et al., 2014). This instability blurs job boundaries and results in role overload, eventually increasing stress. Anxiety, burnout, and depression are repeatedly noted in qualitative literature, aligning with their dominant occurrence in VOSviewer analysis results. Stigma associated with psychological support hampers open discussion on mental health and blocks support-seeking attitudes. NGOs with limited preventive initiatives or psychosocial support face staff disengagement and absenteeism. Studies further revealed that during the COVID-19 pandemic, a significant increase was observed in staff anxiety and distress (Begum et al., 2024).

Data Integration for Essential Insights: NGO Funding: Patterns, Sources, and Volatility

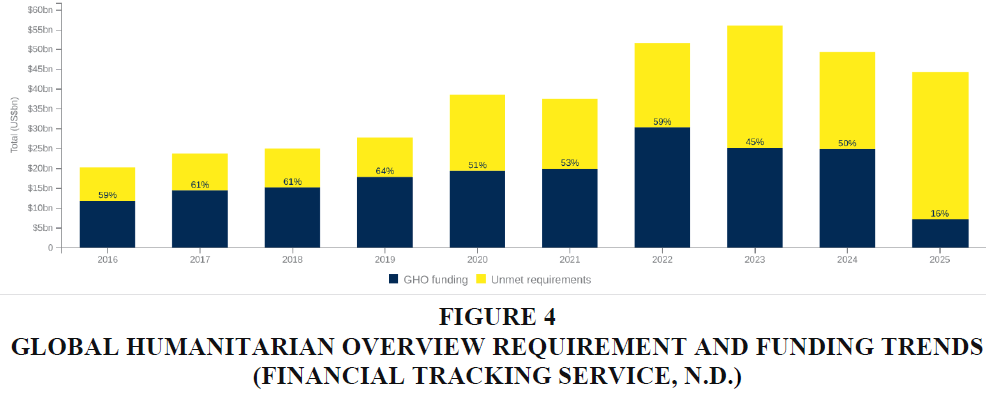

As of the February 2025 update, the Global Humanitarian Overview tracked around $2.32 billion in funding, whereas the required funds were $44.7 billion. Thus, covering only 5.2% of the global need, a crucial data point that shows the issue of underfunding in this sector (Financial Tracking Service, n.d.). Further, the trend of the last 10 years shows an increase in funding from 2016 to 2019 as per the increase in fund demand (Figure 4). However, post-COVID, there is a decline in the availability of funds, leaving behind a larger part of unmet requirements.

Figure 4 Global Humanitarian Overview Requirement and Funding Trends (Financial Tracking Service, N.D.)

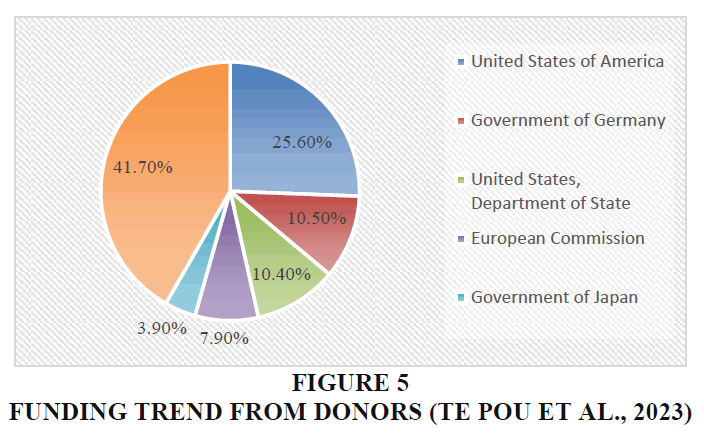

When it comes to major donors, the top three governmental donors include the United States, the European Commission, and Germany, as shown in Figure 5. These three sources account for around 61% of global funding for NGOs, suggesting significant dependence on a few sources and a higher risk of sector-wide instability in case of a shift in major donors.

Figure 5 Funding Trend from Donors (Te Pou et al., 2023)

The “NGO Estimates Report 2022” by Te Pou et al. (2023) provides important data specifically related to NGOs delivering adult alcohol and drug, and mental health services in Aotearoa New Zealand. The data reveals that the total estimated full-time equivalent (FTE) staff, both employed and vacant, as of March 2022, was 5165 positions. This shows an increase of 6% since 2018; population growth was 5%. The vacancy rate almost doubled from 2018 to 2022, at 11%. The instability of the sector is reflected by a recruitment rate of 21% and a resignation rate of 14%. Further, the composition breakdown of NGO staff reveals that 60% are support staff, 21% are registered professionals, and 19% are administrators/managers. Lived experience roles are reported to be 9%, and Maori cultural roles are 6%. Kaupapa Maori NGOs had higher proportions in lived and cultural experience roles, and non-Kaupapa Maori NGOs, although they had larger teams, had higher variability in turnover. The impact of the pandemic was significantly visible in the workforce; the reported reduction in the workforce was 23%, attributed to uncertainty and stressful work environments. The high vacancies are the outcome of understaffing and increasing workload, which has led to stress and burnout.

Recommended Policy Framework

The findings of this study reveal the pervasive psychological toll of uncertainty on NGO staff, driven by interconnected factors related to finance, infrastructure, and human resources. A comprehensive framework is proposed for addressing the issues. The proposed framework in figure 6 is grounded in the theoretical frameworks of the Effort–Reward Imbalance (ERI) Model (Siegrist, 1996), the Job Demand–Control–Support (JDCS) Model (Karasek & Theorell, 1990), and the Conservation of Resources (COR) Theory (Hobfoll et al., 2018).

The aim of the framework is to foster equitable resource allocation, organizational resilience, and proactive mental health support to mitigate the risk of stress, anxiety, and burnout. The three core domains included in the framework are financial resilience, infrastructural enhancement, and human resource sustainability, with the fourth cross-cutting element for implementation and monitoring. The recommendations in this framework are evidence-based, drawing from both systematic literature review findings and quantitative insights.

Financial Resilience and Adaptability

Financial uncertainty, credited to government grant dependencies and volatile donor funding, directly results in emotional exhaustion and job insecurity, as highlighted in various studies (Ali & Gull, 2016; Kermani & Reandi, 2023). To overcome this challenge, the policies should give priority to predictability and diversification. Firstly, NGOs should have multi-source funding so that the dependence on a few dominant donors is reduced. This could be done through the establishment of a collaborative funding pool with local philanthropists, international agencies, and private foundations to ensure that at least 30-40% of the budget comes from flexible sources. Donors and governments could incentivize this through tax benefits or matching grants for diversified portfolios, aligning with COR theory as it safeguards against resource loss spirals (Hobfoll et al., 2018).

Secondly, scenario-based financial planning should be implemented along with reserving funds. NGOs should mandate annual stress testing of funds and budgets, simulating scenarios like economic downturns or donor withdrawal, and having reserves equivalent to around 6 months of operational costs. This practice would reduce the psychological burden of uncertainty, as staff surveys revealed a correlation between financial instability and higher depression rates (Massazza et al., 2023). Thirdly, improve staff involvement and transparency in financial decisions. The quarterly financial health report of the NGO should be shared with the employees, along with a participatory budgeting practice wherein resource allocation is governed by staff input. This helps in building trust and also mitigates ERI imbalance, ensuring that the efforts of the staff are directly connected with the stability of the NGO (Jachens et al., 2019).

Infrastructural Strengthening and Digital Equity

Infrastructural limitations worsen operational stress and isolation, more so in conflict-affected or rural areas, wherein logistical gaps result in professional futility (Malhouni & Mabrouki, 2024; Kermani & Reandi, 2023). The policy in this aspect is focused on adaptive capacity building and equitable access. Primarily, NGOs should invest in physical and digital infrastructure, leveraging targeted grants. Government and donors should allocate funds for specific infrastructure upgrades of NGOs, like secure facilities, high-speed internet, and reliable transportation, particularly for areas with low access rates. Partnership with a technology company could provide what looks like a cloud-based platform at a subsidized rate. This is in accordance with COR theory; preserving important resources like communication channels helps to reduce feelings of isolation (Castanheira, 2024).

Further, NGOs should mandate adaptive training and infrastructure audits. Biannual assessments can be conducted on infrastructural needs, and the staff feedback incorporated to identify gaps that result in workforce stress. Training programs on crisis-resistant operation and digital tools could be designed, with certification, to enhance staff competency. Studies reveal that better infrastructure support leads to a decrease in burnout risks (Navajas-Romero et al., 2020), supporting JDCS by enhancing control over work environments. Lastly, shared infrastructure networks should be promoted. The policy could promote consortia wherein resources of multiple NGOs are pooled for digital hubs or communal facilities, fostering collaboration and reducing individual costs. This could be largely significant in high-uncertainty contexts wherein infrastructure failures increase psychological distress.

Human Resource Sustainability

Human resource challenges like role overload and high turnover directly relate to anxiety and burnout. Policies need to focus on stability, destigmatization, and support. NGOs should start with fair employee practices. It should shift to long-term contracts and offer competitive compensation, funded through dedicated grants from donors. It would address precarity, as studies revealed that short-term roles increase staff stress (Cunningham et al., 2014). Flexible working arrangements should be included to balance demands. Further, proactive mental health support should be integrated into the regular practice of the NGO. Training leaders and managers in supportive supervision could be helpful in reducing stigma and promoting help-seeking behaviors. Mentorship and peer networks are to be formalized to build resilience, aligning with the COR model, by conserving social resources. Lastly, the focus is on diversity and capacity building. The policy should support career pathways, inclusive hiring, and ongoing training. This would enhance workforce retention, with data indicating that growth in specialized roles improves overall morale (Yao et al., 2025).

Cross-Cutting Implementation Strategies

To ensure the efficacy of policies, monitoring practices like annual impact evaluation using standard tools and burnout scales from Jachens et al. (2019) should be included. Multisectoral partnerships with private entities, donors, and the government should encourage knowledge sharing and funding. This framework has the potential to significantly reduce psychological risk based on intervention studies (Castanheira, 2024) and thus foster sustainable NGO ecosystems.

Conclusion

The study has highlighted the profound psychological toll of uncertainty on NGO staff, presenting evidence from a systematic literature review and quantitative data to highlight the interconnection between financial constraints, infrastructural limitations, and human resource challenges. The key themes that emerged from the study are funding volatility triggers burnout and erodes job security, infrastructural deficits amplify stress and isolation, and HR instability fosters stigma and overload. Theoretical frameworks like JDCS, ERI, and COR provided robust lenses for understanding these dynamics, with COR particularly apt in explaining resource loss spirals. The proposed framework offers actionable strategies for the mitigation of these issues.

References

Ager, A., Pasha, E., Yu, G., Duke, T., Eriksson, C., & Cardozo, B. L. (2012). Stress, mental health, and burnout in national humanitarian aid workers in Gulu, Northern Uganda. Journal of traumatic stress, 25(6), 713-720.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ali, T. M. (2016). Impacts of government funding on the mental health non-government organizations in the Northern Territory, Australia. Global Business and Management Research, 8(4), 19.

Ali, T. M., & Gull, S. (2016). Government Funding to the NGOs: A blessing or a curse?. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science, 5(6), 51.

Batti, R. C. (2014). Challenges facing local NGOs in resource mobilization. Humanities and Social Sciences, 2(3), 57-64.

Begum, S., Kabir, R., & Mondal, M. S. H. (2024). Exploring The Impact Of Covid-19 Pandemic On The Mental Health Of Ngo Staff In Bangladesh, Focusing On Stress And Coping. Journal of Sociology: Bulletin of Yerevan University, 15(2 (40)), 50-63.

Bharadwaj, P., Pai, M. M., & Suziedelyte, A. (2017). Mental health stigma. Economics Letters, 159, 57-60.

Bhui, K., Dinos, S., Galant-Miecznikowska, M., de Jongh, B., & Stansfeld, S. (2016). Perceptions of work stress causes and effective interventions in employees working in public, private and non-governmental organisations: a qualitative study. BJPsych bulletin, 40(6), 318-325.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Castanheira, J. A. N. (2024). Mental Health support programs in the Humanitarian sector: Field workers' well-being and perspectives on NGO practices (Master's thesis, ISCTE-Instituto Universitario de Lisboa (Portugal)).

Cunningham, I., Baines, D., & Charlesworth, S. (2014). Government funding, employment conditions, and work organization in non‐profit community services: A comparative study. Public Administration, 92(3), 582-598.

Gilstrap, C. M., Schall, S., & Gilstrap, C. A. (2019). Stress in international work: stressors and coping strategies of RNGO international directors. Communication Quarterly, 67(5), 506-525.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J. P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual review of organizational psychology and organizational behavior, 5(1), 103-128.

Jachens, L., Houdmont, J., & Thomas, R. (2019). Effort–reward imbalance and burnout among humanitarian aid workers. Disasters, 43(1), 67-87.

Karanth, B. (2018). Funds management in NGOs-A conceptual framework. Annamalai International Journal of Business Studies and Research, 1(1), 116-129.

Kermani, F., & Reandi, S. T. A. (2023). Exploring the funding challenges faced by small NGOs: perspectives from an organization with practical experience of working in rural Malawi. Research and Reports in Tropical Medicine, 99-110.

Khudaniya, K. S., & Kaji, S. M. (2014). Occupational stress, job satisfaction & mental health among employees of government and non-government sectors. Int J Indian Psychol, 2(1), 150-8.

Lopes Cardozo, B., Gotway Crawford, C., Eriksson, C., Zhu, J., Sabin, M., Ager, A., & Simon, W. (2012). Psychological distress, depression, anxiety, and burnout among international humanitarian aid workers: a longitudinal study.

Malhouni, Y., & Mabrouki, C. (2024). Mitigating risks and overcoming logistics challenges in humanitarian deployment to conflict zones: evidence from the DRC and CAR. Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management, 14(3), 225-246.

Navajas-Romero, V., Caridad y Lopez del Rio, L., & Ceular-Villamandos, N. (2020). Analysis of wellbeing in nongovernmental organizations’ workplace in a developed area context. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(16), 5818.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Siegrist, J. (1996). Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. Journal of occupational health psychology, 1(1), 27.

Te Pou. (2023). NGO workforce estimates: 2022 survey of adult alcohol and drug and mental health services . Te Pou.

Tugyetwena, M. (2023). A literature review of the relationship between governance, funding strategy and sustainability of non-government organizations. International NGO Journal, 18(2), 10-19.

Van der Doef, M., & Maes, S. (1999). The job demand-control (-support) model and psychological well-being: A review of 20 years of empirical research. Work & stress, 13(2), 87-114.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Received: 28-Jul-2025, Manuscript No. AMSJ-25-16086; Editor assigned: 29-Jul-2025, PreQC No. AMSJ-25-16086(PQ); Reviewed: 10- Aug-2025, QC No. AMSJ-25-16086; Revised: 05-Sep-2025, Manuscript No. AMSJ-25-16086(R); Published: 16-Sep-2025