Research Article: 2026 Vol: 30 Issue: 1

Understanding Tunisian???s Perceived Destination Image Formation Through Online Information Qualities In Social Media

Malek Kohli, Faculty of Economic Sciences and Management of Nabeul, Tunisia

Ayoub Nefzi, University of Orleans, France

Citation Information: Kohli, M., & Nefzi, A. (2026) Understanding tunisian’s perceived destination image formation through online information qualities in social media. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 30(1), 1-10.

Abstract

The current study addresses the impact of social media on the formation of tourist destination image in order to identify which information quality is most appropriate to influence the intention to visit a country. Several empirical steps have been followed to validate the conceptual model put forward. A qualitative study has made it possible to refine our hypotheses whereas a quantitative led to the validation of our conceptual model. Data were obtained from a survey of 310 participants that was carried out to test the impact of information quality on destination image formation. Three major data analysis techniques were used: exploratory factor analysis (EFA), confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and multi-group analysis. In general, the results support most of our hypotheses. The findings show that the quality of information on Facebook web pages has an impact on the cognitive image, but not on the affective one. Furthermore, results also show that both word of mouth and risk perception moderate the relationship between the previously mentioned images.

Keywords

Information Quality, Destination Image, Social Media, Facebook.

Introduction

The current digital revolution in the tourism industry has become increasingly dependent on social media platforms, as they transformed the paradigm of destination marketing where the messages were controlled by the organization towards the dependency on user-generated content (UGC) and peer-to-peer influence (Ketter, 2024). As a result, these platforms are no longer traditional communication channels, but vital structures to travel planning where tourists are pursuing genuine experiences and credible information in order to reduce the perceived risks of destination choice (Zhou et al., 2024). In the context of destinations that face issues with their image, this online realm is considered as a significant frontline in managing their reputation and recovery (Currie, 2020).

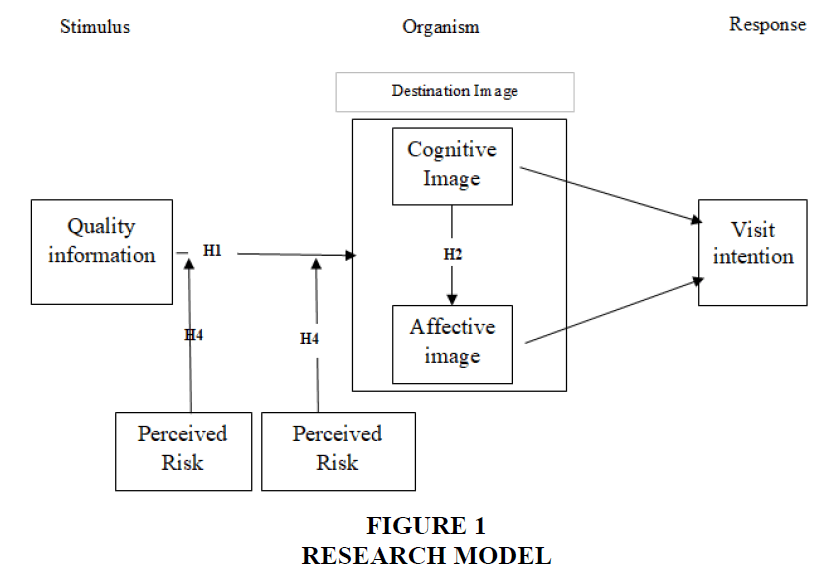

This research applies the Stimulus-Organism-Response (SOR) model developed by Mehrabian and Russell (1974) to provide a theoretical basis of the intricate relationship between digital stimuli and tourist behavior. This framework is well developed and has been widely applied in the context of tourism and hospitality research (Asyraff et al., 2023; Kim et al., 2020), and it provides a solid framework to understand how external factors (e.g., information in social media) contribute to the internal organism (cognitive and affective states) of an individual and, hence, affect their behavioral reactions (e.g., visit intention). Even though the flexibility of the SOR model allows introducing a variety of variables (Yang, 2018), its deployment as a theoretical framework to study the relationship between the qualitative aspects of online information, the development of a multi-dimensional destination image, and the subsequent behavioral purposes has not been systematically studied. Within this SOR framework, the construct of destination image constitutes the critical "Organism" state.

This multidimensional construct, which includes cognitive, affective, and conative components, is now very deeply influenced by the organic processes of social media (Molinillo et al., 2023). And although the overall impact of social media as a stimulus is well established, academic knowledge is still at a critically early stage when it comes to the qualitative features of this information that are more likely to stimulate the creation of images. The extent of social media mentions (Sotiriadis, 2017) has been the most common focal point of research literature, disregarding the crucial role of IQ which includes such dimensions as accuracy, timeliness, and credibility, as an important stimulus. How exactly these dimensions of IQ influence the cognitive and affective aspects of the organismic state, which subsequently give rise to the conative response, is an important gap in theory (Zhou et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2024).

Another factor that increases this gap in theory is a significant contextual gap. Most research on social media and tourism has been conducted in Western and Asian settings (Mariani et al., 2018), and the immediate generalization of the results may be constrained by cultural differences in perceptions, patterns of social media usage, and the destination market positioning. Although recent research has started examining the place of social media in the Gulf Cooperation Council nations (El-Said et al., 2024), the entire MENA region, and Tunisia in particular, is not well represented in the literature. Tunisia is a valid case study: a destination where tourism is one of the pillars of the economy (World Travel & Tourism Council, 2024) but whose image is more susceptible to any changes in reputation, so the strategic management of social media information is not just an opportunity but a necessary measure Wang et al., (2023).

Based on the SOR paradigm, the proposed study will be used to empirically determine the impact of the social media information quality (Stimulus) on the development of a holistic destination image (Organism) and subsequent visit intention (Response) in the context of Tunisia. This study aims to answer the following question: "What are the effects of quality information on social media platforms on tourists’ intention to visit the destination?". To address this problem, we have established three research questions:

1. What are the key dimensions of tourism information quality in social media that act as salient Stimuli for potential tourists?

2. How does the cognitive and affective components of the inner organism, which may be represented as the destination image, differ with the stimuli of these IQs?

3. What is the subsequent effect of this cognitive and affective Organism on the conative Response (visit intention)?

This research includes some significant contributions to the answers of these questions. Theoretically, it advances the application of the SOR model in tourism by precisely mapping the pathway from specific digital stimuli (IQ dimensions) through the organismic state (cognitive & affective image) to a behavioral response. Additionally, it offers a more detailed, mechanism-based understanding of destination image creation due to the integration of the modern construct of IQ through information systems into the tourism social media literature, thus fulfilling the request of more detailed analyses (Zhou et al., 2024). Holding the methodological perspective, the research provides a powerful analysis of a holistic model in an under-explored setting, therefore, broadening the geographical scope of the field. In practice, the results provide actionable implications to Destination Marketing Organizations in Tunisia and similar markets in terms of strategic management, selection, and promotion of high-quality social media content, thereby facilitating the appropriate construction of destination image and triggering visitation.

Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

The Stimulus-Organism-Response Theory

Mehrabian and Russell (1974) first described the SOR model, which outlines the casual chain by which stimuli in the external environment moderate the internal state of the organism, and hence, cause responses in behavior. In the given study, the stimulus element refers to external influences, such as the quality of information shared on social media. The organism is used to describe the thinking and feeling processes taking place in the minds of tourists, whereas the response refers to the intention to visit a given destination.

Social media in tourism

Social media is a set of Internet-based applications that have been created on a participatory Web 2.0 platform and allow global users to co-create value by sharing ideas, experiences, and information (Kapoor et al., 2018). These channels have gone beyond the social aspect of their inception to become invaluable organizational resources that are essential in interacting with customers, brand building, and direct marketing communicating (Dwivedi et al., 2021). This development is especially prominent in the tourism sector, where the aesthetic and sensory quality of the product is in line with the capabilities of platforms like Instagram, Tik Tok, and Facebook (Buhalis & Moldavska, 2022). The informational utility of these platforms is one of the major contributors to their value; individuals engage in searching and sharing content to minimize uncertainty and solve decision-making issues, a behavior that is often referred to as informational usage (Molinillo et al., 2021 However, even with the acknowledged power of user-created content, there is still a severe gap in comprehending what exactly are the qualitative features of such content, i.e., Information Quality (IQ), which supports the impact of user-created content on tourist decision-making (Cheng & Wei, 2023; Zhou et al., 2024).

Quality of Information

The essence of Information Quality (IQ) is that it is fit, i.e., conforms to the requirements of users and their expectations of information (Chen et al., 2020). In the context of the hospitality and tourism sector, such definition denotes that the usefulness of the available information helps tourists evaluate travel products and make informed decisions, thus alleviating perceived risk (Zhou et al., 2024). A multidimensional conceptualization of IQ is often operationalized.

Intrinsic Information Quality

The dimension refers to the quality of information, which is inherent, regardless of contextual or task-related factors. It is related to the nature of the data itself. The main qualities are accuracy (i.e., is free of error), objectivity (i.e., is free of bias), believability (i.e., is perceived to be trustworthy), and the credibility of the source (Cheng &Wei, 2023; Park and Nicolau, 2024). When applied to the area of tourism and social media, it means that user-created reviews or posts need to be perceived as credible and factual to have influence.

Contextual Information Quality

Contextual IQ puts a strong emphasis on the need to assess information in terms of situational context of the task the user is performing. Information should be relevant to the decision being made at the stage of the travel, timely, corresponding to the situation in the destination, and exhaustive in its scope besides being provided in a relevant quantity that neither is too insufficient nor overwhelming (Sann et al., 2023). As an illustration, a message about the current COVID-19 measures in a hotel has a high contextual value to a tourist who decides to make a trip at the time in question.

Quality in Representational information

This dimension is concerned with how the information is formatted and presented so that it will be easily interpreted and understood by the user. It includes the following: coherence in formatting, coherence in structure, interpretability, and understandability (Zhou et al., 2024). Within the framework of social media, it refers to the clarity of the information presented in a text form, visual (such as a well-built carousel on Instagram), or video form, thus making it easy to digest by potential tourists.

Information Accessibility

Information Accessibility deals with the ease of access to information. In the digital era, this aspect is deemed to be fundamental, because information is of little significance when it is not accessible. The concept involves the ease of access, availability of the platform, and the security of the system (Molinillo et al., 2021). In the case of tourism-related social media, these media need to be constantly online, allow users to easily search and navigate the content and also make users feel that their data are secure whenever they access information regarding travels.

Destination Image

Destination image is a pivotal concept in tourism, recognized as the sum of beliefs, ideas, and impressions that a person holds of a place (Baloglu & McCleary, 1999, Stylos et al., 2016). This mental image does not serve as a passive cognitive process but rather as a decisive factor that directly influences the decision-making process of the tourist, including the destination choice, post-research analysis, and Word-of-mouth feedback (Afshardoost & Eshaghi, 2020). As such, a tripartite construct has been the focus of the literature whereby destination image can be viewed as a combination of three interdependent dimensions, namely cognitive, affective, and conative (Baloglu and McCleary, 1999; Li and Stepchenkova, 2022; Zhang et al., 2024).

Cognitive Image

The cognitive element is associated with the beliefs and knowledge of an individual about the tangible and intangible features of a destination (Baloglu and McCleary, 1999; Pike and Ryan, 2004). This element includes analyses of the infrastructural facilities in the destination, attractions, natural landscapes, and cultural events (Agapito, 2020). In the modern digital environment, the process of creating destination knowledge is increasingly mediated by user-generated content distributed through social media platforms, as potential tourists form ideas about the physical characteristics of a destination before it is ever visited (Marine-Roig, 2019).

Affective image

The affective aspect symbolizes an individual’s feelings towards an object or a destination, the latter being favorable, neutral, or unfavorable (Kim, 2021). It goes beyond knowledge of facts to include the emotional appeal that a destination conveys (Chen and Uysal, 2003; Kim and Richardson, 2003). With potential travelers being exposed to stimulating visuals and stories on apps like Instagram and Tik Tok, the affective image is created, and thus, has a decisive role to play in the stage of destination selection (Ketter, 2024).

Conative image

The conative element refers to the behavioral product of cognitive and affective assessments. It is the final stage of the sequential process and takes the form of an intention to visit, to recommend the destination to others, or to engage in positive word-of-mouth (Baloglu & McCleary, 1999; Gartner, 1993; Jiang & Lyu, 2022). This behavioral intention is the ultimate indicator of a successful destination image and the primary goal of marketing efforts.

Hypotheses development and conceptual framework

Relationships between cognitive, affective, and conative destination images

The construction of destination images is hierarchical and sequential in nature, and the conceptual framework of the process consists of three mutually-dependent dimensions: cognitive (beliefs &knowledge), affective (feelings and emotions), and conative (behavioral intentions) (Gartner, 1993; Stylos et al., 2016).

In the modern digital context, it is assumed that this three-part structure is fully functional, and social media platforms are viewed as the primary medium through which the structure is built. Our preliminary qualitative analysis suggests that this process is initiated by the cognitive dimension. The informational (posts, descriptions) and visual (photos, videos) content on social media pages provides potential tourists with the necessary knowledge to form beliefs about a destination. Based on the existing literature (e.g., Pike and Ryan, 2004; Agapito et al., 2013) and supported by more recent empirical data (Li and Stepchenkova, 2022), the aforementioned cognitive assessment can be viewed as a precondition to the affective response. In other words, what one knows about a place directly influences what one feels about it. The overall appraisal, arising as a result of the interaction between cognitive and affective elements thus, predisposes the development of a behavioral intention, or so-called conative image (Konecnik and Gartner, 2007; Afshardoost & Eshaghi, 2023). This intention is seen as expressed willingness to come to the destination, to recommend to the destination to others, or to engage in positive word-of-mouth communication.

In spite of the fact that the hierarchical model has strong theoretical support, its empirical confirmation in the specific environment of social media is limited (Zhang et al., 2024). Few studies have quantified the sequential links between these three dimensions when the image is primarily shaped through user and marketer generated content on platforms such as Facebook.

Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1: The cognitive image has a positive and significant influence on the affective image of a destination formed via social media.

H2: The cognitive image has a positive and significant influence on the conative image of a destination formed via social media.

H3: The affective image has a positive and significant influence on the conative image of a destination formed via social media.

Relationship between tourism information quality and cognitive / affective image

The very notion of destination image is built up hierarchically, including cognitive, affective, and conative elements (Li and Stepchenkova, 2022). Social media platforms are the main channels through which the environmental stimuli are exchanged, forming this dynamic and interactive framework of image formation in the digital era. The connection between information sources and the destination image construction is well-documented. Modern literature attests that the quality of information is an essential characteristic of information sources, which is a vital stimulus that directly affects the cognitive and affective aspects of the destination image (Marine-Roig, 2019).

Despite the fact that classic commercial media are still relevant, social media platforms are currently taking the lead as a source of information due to their perceived credibility and the persuasive power of UGC. Peer-to-peer content receives more trust among modern travelers than organizational marketing messages because they recognize UGC as more genuine and unbiased (Ketter, 2024).

According to the recent empirical research, information quality dimensions have a significant impact on the way consumers process travel information and shape destination perceptions (Zhou et al., 2024). Our qualitative review establishes four major information-quality dimensions within the framework of social media that are particularly acute to consider: reliability, understandability, information volume, and engagingness. Then, we can formulate the following hypotheses:

H4. Social media tourism information quality is positively associated with cognitive destination image.

H5. Social media tourism information quality is positively associated with affective destination image.

Reliability

Reliability as a concept is perceived as the accuracy and plausibility of information (Cheng & Wei, 2023). In social media contexts, source credibility becomes extremely crucial, and travellers become more dependent on peer-generated information compared to commercial messages (Park & Nicolau, 2024). The Credibility of experiences that users share has a significant impact on how target tourists develop cognitive and affective responses to destinations.

H4a: Information reliability positively influences cognitive destination image.

H4b: Information reliability positively influences affective destination image.

Ease of Understanding

This aspect relates to the readability and understandability of the information presentation (Sann et al., 2023). Properly organized content with the use of multimedia tools promotes learning, whereas the use of technical terminology or vague expressions may pose cognitive barriers. Understandable information enhances better mental model creation and emotional attachment to destination attributes.

H5a: Information understandability positively influences cognitive destination image.

H5b: Information understandability positively influences affective destination image.

Amount of Information

The construct relates to the perceived sufficiency and suitability of the amount of information necessary to make a decision (Zhou et al., 2024). Even though adequate information contributes to the formation of a cognitive image, providing the necessary information about destination attributes, it seems to have a limited effect on the affective image. As Gartner (1993) noted, information quantity primarily affects cognitive rather than emotional processing.

H7a. Information amount positively influences cognitive destination image.

Interestingness

The level of material that is perceived as interesting, intriguing, and thought-provoking is referred to as interestingness (Ketter, 2024). Compelling stories and inventive posts on social media create stronger interest and stimulate the desire to explore, which in turn influences the cognitive processing and emotional attitude towards destinations.

H6a. Information interestingness positively influences cognitive destination image.

H6b. Information interestingness positively influences affective destination image.

Word-of-Mouth as a Social Influence Moderator

WOM represents informal communications between consumers concerning their evaluations of products and services. Studies have consistently shown that WOM is a more powerful tool in influencing consumer behavior than the conventional marketing communication, which is explained by a number of factors (Litvin et al., 2018). First, personal network messages, friends, family, and peers, are more likely to receive increased credibility and relevance when it comes to travel decision-making (Ketter, 2024). Second, peer-generated information is considered more reliable and authentic than the sources of information created commercially (Park and Nicolau, 2024). The valence of WOM messages is especially critical: positive WOM messages promote the attractiveness of the destination, and negative reviews can significantly harm the perceptions and visit intentions of the destination (Jalilvand et al., 2020; Yousaf et al., 2023).

Our qualitative approach, supported by available literature, indicates that WOM is likely to mediate the correlation between the quality of information on social media and destination image formation. Hence, information quality credibility and social validation offered through WOM communications can either enhance or weaken the impact of information quality on the cognitive and affective evaluation of a destination.

H8: Word-of-mouth moderates the relationship between social media information quality and (a) destination image formation and (b) visit intention.

Perceived Risk as a Contingent Moderating Variable

Perceived risk is a contextual moderator, which summarizes the subjective evaluation of uncertainty and possible negative consequences affecting travel-related decision-making among consumers (Rather, 2021). Contemporary tourism research identifies multiple risk dimensions relevant to destination choice such as; health and safety risks, financial risks; psychological risks, physical risks, terrorism risks and so on. The recent happenings in the world, such as pandemics and geopolitical conflicts have increased risk perception as an essential factor in making travel decisions (Wen et al., 2023).

When there are high levels of risk perceptions, destination image does not serve as a predictor of tourist behavior. Travelers who hold a lower risk perception show greater intentions to visit as confirmed by our qualitative data, as Law (2006) found.

The Tunisian setting has specific significance in analyzing the risks impact. According to research studies regarding the recovery of tourism in the aftermath of the revolution, the risk perceptions play a major role in the destination selection (Khan et al., 2023). Risk perception is also a probable boundary condition which alters the information quality that affects destination evaluation. In high-risk situations, consumers are more critical in the information processing and they can discount positive information, unlike low-risk situations where positive information processing is easier (Sanchez-Canizares et al., 2024).

H9: Perceived risk mediates the relationship between social media information quality and destination image formation as well as visit intent, with stronger relationships existing in situations of low perceived risk.

Based on the theory and the previous discussion, we have formed the research model presented in Figure 1.

Research Methodology

This study follows a two-stage process for data collection, using unstructured (qualitative) and structured (quantitative) methods.

Qualitative research

The qualitative investigation, with the needed variables being enriched, will help refine our hypotheses, figure out tourists’ most used social media platforms, and know about the most recurrent dimension of information quality they consider. However, limiting the amount of data in focus is vital because it’s too overwhelming for practical use and drawing strategic insights. To do so, we conducted semi-structured interviews through a survey using open-ended questions. Our interviews (15) took place between June and August 2025 and they were conducted face-to-face with international tourists from all over. As such, our sample consists of 15 interviewees (9 women and 6 men) aged 33 to 70. Each interview lasted approximately 35 minutes. We used a manual thematic content analysis. Results showed that Facebook is the most used social media platform by tourists seeking information. They also validated that reliability, amount of information, ease of understanding and interestingness are the most factors to influence destination image. Last but not least, we figured out that WOM and perceived risk moderate the link between quality of information and the destination image formation.

Quantitative research

Measure and questionnaire development

Measurement scales that were used in the study under consideration were taken out of the empirically-tested tools, with few adjustments being made to fit the specific situation of the study. The questionnaire had four major parts (destination image formation (Part 1), quality of information that relates to Facebook pages (Part 2), word-of-mouth (WOM) and perception of risk (Part 3), and demographic profile (Part 4).

The measurement scale developed by Kim et al. (2017), comprising seven items, was adopted to assess the cognitive image. The affective image component included four bipolar dimensions, gloomy/exciting, unpleasant/pleasant, sleepy/arousing, and distressing/relaxing, based on the same study. To evaluate travel intention, the scale proposed by Jalilvand et al. (2013) was used; this three-item scale, originally adapted and refined from Kassem et al. (2010), has also been applied by Jalilvand (2016). The reliability construct was measured using the scale developed by Xu and Chen (2006), while information reliability was assessed through four items proposed by Ha and Ahn (2011). The credibility construct was measured using the scale from Chen et al. (2014). To evaluate understandability, three items from Xu and Chen (2006) were utilized. The amount of information construct followed the scale by Chai et al. (2009), as used in Kim et al. (2017). Similarly, the scale from Kim et al. (2017) was adopted to measure the interestingness of Facebook page content within the tourism context. The measurement tool that was adapted to facilitate the construct of risk perception was based on the scale that was first introduced by Gallarza and Saura (2006), informed, in its turn, by the scales initially introduced by Tsaur et al. (1997), Cooper et al. (1993), and Seddighi et al. (2001). The WOM construct was measured using the scale developed by Jalilvand (2016). These scales were chosen for two main reasons. First, they have been previously applied in similar research contexts, specifically, tourism in social media environments. Second, all constructs showed a Cronbach alpha and composite reliability (CR) of above 0.70, showing strong internal consistency. A five-point Likert scale was employed for all measurement items.

Data collection

We used a survey with a questionnaire and we administered it to tourists. We resorted to "Discover Tunisia" Facebook page in order to answer our research questions. We chose this page because of the number of likes (323 K person). Moreover, we interviewed some professionals in the tourism industry who mentioned that “Discover Tunisia" page is the most used Facebook page. We sent the questionnaire via e-mail to people who had not visited Tunisia yet, and we posted our questionnaire on some other Facebook pages such as «Wanted France", "Fordham Business School". Our study was administered in three phases; First came the pre-test phase in which we directly administered our questionnaire to fifteen tourists and we assisted them to identify any problems of clarity, readability or comprehension. The second phase was operated subsequently and in which adjustments to the data collection instrument and the first data purification (major factor analysis) occurred. We administered our questionnaire to both thirty-five tourists (pre-test) and final sample (310). Finally came the third phase in which the final administration of the final questionnaire (exploratory factor analysis) took place.

We are exhibiting its description in the following Table 1

| Table 1 Sample Characteristics | |||

| Variable | Value | Frequency | Percentage |

| Gender | Female | 170 | 54.8% |

| Male | 140 | 45.2% | |

| Age | Under 24 years | 105 | 33.9% |

| Between 25 and 34 years | 135 | 43.5% | |

| Between 35 and 44 years | 55 | 17.7% | |

| Between 45 and 54 years | 5 | 1.6% | |

| Over 55 years | 10 | 3.2% | |

| Level of Education | Primary or secondary school | 5 | 1.6% |

| High school | 10 | 3.2% | |

| Higher education | 270 | 87.1% | |

| Others | 25 | 8.1% | |

| Occupational category | Student | 115 | 37% |

| Employee | 105 | 33.9% | |

| Self-employed | 65 | 20.9% | |

| Housewife | 10 | 3.2% | |

| Job Search | 5 | 1.6% | |

| Retired | 15 | 4.8% | |

| Household monthly income ($) | Up to 1,000 | 75 | 24.1% |

| 1,000–3,000 | 110 | 35.4% | |

| More than 3,000 | 125 | 40.3% | |

Results

To test our hypotheses, we used exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses within the framework of structural equation modeling using SPSS 23 and AMOS 23 software. First, we carried out an exploratory factor analysis using principal component analyses on the pre-test sample (N=53) in order to purify the measurement scales. Then, a second data collection on the final sample of the 310 respondents took place to verify the relevance of the chosen solution.

Results of exploratory factor analysis

The primary structure of the questionnaire comprised 38 items meant to measure the study constructs. Hence, the overall number of items was reduced to 33. We eliminated two items from the cognitive image and three items from the perceived risk measurement scale due to a bad quality of representation (<0.5). As a result, we obtained a good value of Bartlett's test of sphericity, an acceptable value of KMO (>0.7) and a Cronbach's alpha greater than 0.6 (between 0.87 and 0.95), which demonstrates a good level of reliability (see Table 2 below).

| Table 2 Results of the Exploratory Factor Analysis | ||||

| Dimension | Items | KMO | Variance explained | Cronbach's Alpha |

| Cognitive image | 5 | 0.713 | 66.55 | 0.871 |

| Affective image | 4 | 76.42 | 0.928 | |

| Cognitive image | 3 | 41.13 | 0.875 | |

| Interestingness | 3 | 0.695 | 80.98 | 0.881 |

| Understandability of content | 3 | 0.716 | 75.48 | 0.836 |

| Amount of information | 3 | 0.583 | 70.21 | 0.787 |

| Reliability | 3 | 0.661 | 78.25 | 0.861 |

| Risk perception | 5 | 0.840 | 69.11 | 0.888 |

| WOM | 4 | 0.730 | 74.41 | 0.882 |

Results of confirmatory factor analysis

In a second step, we carried out a confirmatory factorial study by applying a structural equation analysis on the final sample (N=310). We tested the quality of fit of the global model. This is considered an acceptable quality of fit since the absolute, parsimony and incremental indices have values that respect the standards mentioned above. We obtained a rather satisfactory quality of fit despite the fact that the GFI and AGFI have values of 0.867 and 0.829 respectively, both slightly lower than 0.9. However, they still met the requirement suggested by Baumgartner and Homburg (1995), and Doll et al. (1994), bearing in mind the fact that the value of GFI and AGFI is acceptable if it is above 0.8. Also, RMSEA is taken into consideration within the standards. The CMIN/DF is acceptable and underlines a good fit. Table 3 shows an acceptable quality of fit since the absolute, incremental and parsimony indices are excellent.

| Table 3 GOF Measures of the Measurement Model | ||||||||

| X² | GFI | AGFI | RMR | RMSEA | TLI | NFI | CFI | CMIN/DF |

| 527.703 ddl=197 P=0.000 |

0.867 | 0.829 | 0.066 | 0.074 | 0.923 | 0.900 | 0.934 | 2.679 |

Convergent and discriminant measurement validity

The reliability coefficients (Rhô Jöreskog) are greater than 0.7 (between 0.74 and 0.97), attesting to a satisfactory reliability as recommended by Fornell and Larcker (1981). The average AVE variances of each construct are all greater than 0.5, which confirms a very satisfactory convergent validity of the different constructs. (see Table 4 below).

| Table 4 Reliability and Convergent Validity | ||

| Destination image dimension | RHO VC | RHO JORESK |

| Conative | 0.934 | 0.977 |

| Cognitive | 0.529 | 0.818 |

| Affective | 0.503 | 0.748 |

| Interestingness | 0.557 | 0.791 |

| Understandability of content | 0.641 | 0.840 |

| Amount of information | 0.737 | 0.893 |

| Reliability | 0.684 | 0.866 |

Results of structural equation analysis

We analyzed the obtained results by the structural equations method on the Amos 23 software. We employ structural equation modelling to confirm the effect of Facebook quality of information on the destination image formation once the validity and reliability of the measurements were established. We analyzed the obtained results by the structural equations method on the Amos 20 software. Table 5 shows the fit measures standards. The CMIN/DF, RMR, RMSEA, TLI, NFI and CFI are acceptable and underline a good fit. Also, the values of GFI, AGFI are 0.866 and 0.829 respectively. They are considered satisfactory quality of fit since they are above 0.8 as suggested by Baumgartner and Homburg (1995), and Doll et al. (1994). Thus, the model adjusts to the data and presents a good quality of fit. We believe that the model precision of fit is satisfactory enough to retain the model and to study structural links. The causal link between the two variables is considered significant if the "critical ratio" is CR> 1.96 and P<5%. In our case, the different structural coefficients are quite significant (<P=5%) and (CR>1.96). They also confirm most of our research hypotheses except three of them (H5a, H4b, H5b and H6b). Of the 10 relationships proposed, 6 are supported. Results of the hypothesis testing are summarized in the Table 6.

| Table 5 GOF Measures of Structural Model | ||||||||

| X2 | GFI | AGFI | RMR | RMSEA | TLI | NFI | CFI | CMIN/DF |

| 527.995 ddl=198 p= 0.00 |

0.866 | 0.829 | 0.066 | 0.073 | 0.924 | 0.900 | 0.935 | 2.667 |

| Table 6 Results of the Hypothesis Test | |||||||

| Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | ||||

| H1 | Affective | <--- | Cognitive | 0.280 | 0.064 | 2.905 | 0.004 |

| H2 | Conative | <--- | Cognitive | 0.345 | 0.118 | 4.939 | 0.000 |

| H3 | Conative | <--- | Affective | 0.149 | 0.181 | 2.116 | 0.034 |

| H4a | Cognitive | <--- | Reliability | 0.299 | 0.093 | 2.795 | 0.005 |

| H5a | Cognitive | <--- | Understandable | -0.095 | 0.095 | -0.885 | 0.376 |

| H6a | Cognitive | <--- | Interesting | 0.347 | 0.083 | 4.056 | 0.000 |

| H7a | Cognitive | <--- | amount_information | 0.183 | 0.086 | 2.003 | 0.045 |

| H4b | Affective | <--- | Reliability | 0.078 | 0.070 | 0.640 | 0.522 |

| H5b | Affective | <--- | Understandable | 0.218 | 0.065 | 1.942 | 0.052 |

| H6b | Affective | <--- | Interesting | 0.022 | 0.065 | 0.224 | 0.823 |

As predicted, the cognitive image was undoubtedly associated with the affective image (C. R= 2.905, p=0.004), and the affective image was in its turn associated with the conative image (C. R= 2.116, p=0.034), strongly supporting H1 and H3, respectively. In addition, the hypothesis conveying a relationship between cognitive image and conative image (H2) is also supported (C.R = 4.939, p =0.000). Thus, the carried-out tests confirm the theoretical literature results derived from the(Pike & Ryan, 2004; Agapito et al., 201, Li & Stepchenkova, 2022, Konecnik & Gartner, 2007; Afshardoost & Eshaghi, 2023). Hypotheses H1, H2 and H3 of the research are validated. Besides, the reliability was found to be importantly related to cognitive image (C. R= 2.795, p= 0.005), supporting H4a. Likewise, we could find important relationships for H4a (amount of information and cognitive image) since C. R= 2.003, p=0.045. Moreover, interestingness was related to the cognitive image (C. R= 4.056, p= 0.000). However, in what relates to the role of content understandability, it was not significantly associated with a destination’s cognitive image (C. R= -0.885, p=0.376). The hypotheses supporting H4a, H6a and H7a are validated. However, H5a is not validated. What is more is that the role of understandable content was not significantly associated with the affective images (C. R= 1.942, p=0.052). Also, H4b is not supported since we noticed that the relationships between reliability and affective image are not that significant (C. R= 0.640, p=0.522). Besides, the interestingness was not significantly associated with the affective image (C. R= 0.224, p= 0.823). H4b, H5b and H6b are not supported.

Moderating Impact of Word of Mouth and Perceived Risk

We used a multi-group to test the moderating effect of the WOM and the perceived risk.

Moderating role of the WOM

The Chi-square difference between both constrained and unconstrained models is significant since the Δχ2= 109.036 with p= 0.000. In other words, the link between QI and DIF depends on the WOM. Therefore, hypothesis (H8) is accepted. Thus, we can conclude that WOM has a moderating effect on the impact between the quality of information on Facebook and destination image formation, but it is necessary to check the fit of the model before generalizing conclusions. The quality of fit measures shows that they are well adjusted. This observation allows us to validate hypothesis (H8) of the research Table 7.

| Table 7 Multi-Group analysis of Moderator Variable WOM | ||||||||

| Relation | Group 1 | Group 2 | ||||||

| Coef. stan | Cr | P | Coef. stan | Cr | P | |||

| Affective | <-- | Cognitive | 0.284 | 2.611 | 0.009 | 0.189 | 1.034 | 0.301 |

| Conative | <-- | Cognitive | 0.493 | 6.502 | 0.000 | -0.387 | -3.417 | 0.000 |

| Conative | <-- | Affective | -0.109 | -1.454 | 0.146 | 1.072 | 5.818 | 0.000 |

| Cognitive | <-- | Reliability | 0.270 | 2.056 | 0.040 | 0.355 | 1.531 | 0.126 |

| Cognitive | <-- | Understandable | -0.073 | -0.640 | 0.522 | -0.376 | -1.219 | 0.223 |

| Cognitive | <-- | Interesting | 0.291 | 2.889 | 0.004 | 0.708 | 3.944 | 0.000 |

| Cognitive | <-- | Amount _ Information |

0.177 | 1.766 | 0.0 77 |

0.198 | 0.921 | 0.357 |

| Affective | <-- | Reliability | -0.131 | -0.875 | 0.381 | 0.345 | 1.645 | 0.100 |

| Affective | <-- | Understandable | 0.141 | 1.096 | 0.273 | 0.627 | 2.701 | 0.007 |

| Affective | <-- | Interesting | 0.157 | 1.295 | 0.195 | -0.314 | -1.669 | 0.095 |

Moderating role of the perceived risk

We divided our sample (n=310) into two groups (low risk =115 and high risk=195). The Chi-squared difference test between the constrained model and the unconstrained model is significant (Δχ2= 100.647 with p= 0 %). This result suggests a moderating effect since p<0.05, but it is necessary to check the quality of fit before concluding. The quality of fit measures shows that they are well adjusted. This observation allows us to validate hypothesis (H9) of our research Table 8.

| Table 8 Multi-Group analysis of Moderator Variable Risk Perception | ||||||||

| Relation | Group 1 | Group 2 | ||||||

| Coef. Stan | cr | P | Coef. Stan | Cr | P | |||

| Affective | <-- | Cognitive | 0.22 | 1.17 | 0.24 | 0.302 | 2.789 | 0.005 |

| Conative | <-- | Cognitive | -0.40 | -3.68 | 0.000 | 0.494 | 6.507 | 0.000 |

| Conative | <-- | Affective | 1.08 | 7.31 | 0.000 | -0.115 | -1.485 | 0.138 |

| Cognitive | <-- | Reliability | 0.39 | 1.721 | 0.085 | 0.263 | 2.011 | 0.044 |

| Cognitive | <-- | understandable | -0.409 | -1.34 | 0.180 | -0.070 | -0.625 | 0.532 |

| Cognitive | <-- | Interesting | 0.699 | 4.555 | 0.000 | 0.292 | 2.905 | 0.004 |

| Cognitive | <-- | Amount of information | 0.231 | 1.082 | 0.279 | 0.178 | 1.782 | 0.075 |

| Affective | <-- | Reliability | 0.343 | 1.633 | 0.103 | -0.189 | -1.231 | 0.218 |

| Affective | <-- | understandable | 0.618 | 2.778 | 0.005 | 0.126 | 0.977 | 0.329 |

| Affective | <-- | Interesting | -0.334 | -1.74 | 0.080 | 0.207 | 1.661 | 0.097 |

Discussion

This research sheds light on the relationship between the formation of destination image and tourism IQ factors in social media. The findings suggest that different features of tourism IQ in social media are related to various components of destination image. We further examine our results with regard to quality of tourism information on Facebook and destination image formation as follows. Some basic findings have contributed to our knowledge concerning the behavior intention to pay a visit to a particular tourist destination (Tunisia). First of all, our empirical results have proved that both reliable (H4a), and interesting content (H6a), added to a great amount of information (H7a) are very important determinants of the cognitive image, confirming both Frias et al. (2008) and Vich-i-Martorell (2003) theory. Moreover, our empirical evidence has revealed that most quality of tourism information have a considerable impact on the cognitive image except for understandability of content (H5a). Unexpectedly, the findings also illustrate that the tourism quality of information in Facebook has no significant relationship with the affective image of a destination (Hb was rejected). In fact, results have demonstrated that the reliability of tourism information factor influence the cognitive images (H4a). Hence, tourists’ generated information is considered more credible and trustworthy than that generated by private sector businesses. Eventually, this information help tourists create their cognitive image and know more about a specific destination. This conclusion is also consistent with the results drawn from the literature of Litvin et al., (2008) as well as (Arsal, (2008) and Wheeler, (2009)) in Myunghwa & Micheal (2014)). However, although we originally expected the reliability to have a relationship with the affective image (H4b), our finding is counterintuitive.

Indeed, we also hypothesize that the amount of information influences the destination image formation, particularly on a cognitive level (H7a), which is proven to be real. Moreover, the amount of information is found to have a significant impact on the cognitive image formation; We can conclude that the amount of information can help tourists know what to do and where to find appropriate data about a destination. Whence, the conformity of this result can be seen in the literature of Baloglu and McCleary (1999); and Gartner (1993). Moreover, our empirical data analysis show that the interestingness of tourism information is associated only with the cognitive image formation and not with the affective image (H6a, H6b, respectively). This is a satisfying result as interestingness might be more related to the cognitive image (someone’s destination knowledge) rather than to the affective image (someone’s feelings and emotions). The results validate this proposition and go hand in hand with the those of Chen et al. (2014).

Nevertheless, the understandability of the content that exists on Facebook pages (H5a, H5b) didn’t have a significant relationship neither with the cognitive image nor with the affective one. Hence, results may seem counterintuitive with the evidence of Cheung et al., (2008). Yet, there are some explanations for these findings such as the problem of languages, differences in culture among many other factors.

In addition, it is necessary to mention that both WOM and perceived risk play important roles as moderating variables, contributing to the relationship between QI and DIF as showed our research’s results. We also assumed that the more WOM is positive, the higher is the influence of the information quality on the intention to visit a destination (H8). Our research pinpointed that the information obtained from influential groups is considered credible and trustworthy, that is why, word of mouth might be more influential than commercial sources. The findings of Litvin et al., (2008); Subsequently, Doosti et al. (2016) and Trusov et al. (2009) confirmed our research results stating that word of mouth might moderate the relationship between the quality of information in Facebook and destination image formation (H8).

This paper illustrates a significant relationship between perceived travel risks and destination image. According to Fuchs and Reichel (2011), research on travel risk is well-established. Nevertheless, the link between perceived travel risks and destination image has not been significantly investigated by previous literature. The study’s findings identify a moderator role of the perceived risk: the lower is the perceived risk, the greater is influence of information quality on the intention to visit a destination (H9). These results are in perfect consistency with the empirical studies of Lehto et al. (2008) and Lepp et al. (2011).

Finaly, our research findings validated that destination image is created by cognitive, affective, and conative elements, in the context of international tourists following “Discover Tunisia” Facebook page. These findings are consistent with the research of Gartner (1993); Pike and Ryan (2004); Konecnik and Gartner (2007); Tasci et al. (2007); Agapito et al. (2013). Our results underline that tourists’ motivation, particularly their intention to pay a visit, is much higher when they learn about the visitor attractions of their target destination. Within the hypotheses developed in an attempt to test the relationship between information quality factors and destination image formation, chiefly, the impact of the cognitive image on the affective destination image is realized. Our findings reveal that cognitive and affective determinants have an effect on behavioral intentions of tourists. These results reinforce other papers which highlight the importance of impact in destination image, and mention that the willingness to react positively to the place can be higher when the tourists doesn’t only develop positive feelings to the target destination, but retains positive knowledge of the place (Agapito et al., 2013).

The paper makes a significant contribution to the knowledge on tourism. To begin with, it supports the hierarchical destination image formation model in the context of social media and, as a result, validates the cognitive-affective- conative sequence identified by Gartner (1993) and subsequently confirmed by Stylos et al. (2021). Secondly, it provides a subtle sensitivity to the differences in the information quality of various dimensions affecting different aspects of the destination image. As a practitioner, these findings provide strategic insights on destination marketing organizations (DMOs). In particular, the high salience of information reliability, interest, and adequacy suggests that these aspects should be given priority by DMOs when developing their social-media content strategies. Moreover, the moderating factor of word-of-mouth and perceived risk highlights the necessity of the interdisciplinary communication practice that can simultaneously respond to social factors, risk perceptions, and improvements in the quality of information.

Conclusion

The current study sought to empirically investigate how the social media information quality (IQ) affects the development of the destination image using the Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R) theoretical framework, since very little empirical evidence has been supplied. In fact, this study is one of the few works that particularly focus on the part played by tourism information quality in forming Facebook users’ destination image. To attain this ultimate goal, we formulated a conceptual model that we tested by means of a qualitative method. Also, by using the thematic content analysis, we could summarize that all reliability, amount, understandability and interestingness of information contents are the most important features of tourism information quality. Then, we carried out a survey questionnaire as a quantitative methodology to collect the information needed for our investigation. This study sample was determined by the random sampling method (310 respondents). Data were analyzed using factors analyses such as EFA and CFA by the SPSS 20 and the AMOS 20, respectively. Indeed, the present paper gave us the opportunity to test several direct links to our model.

Strong evidence indicates that the S-O-R model provides a powerful analytical tool to explain the digital tourist decision-making process. Particularly, we show that the Information Quality on Facebook pages, which is measured through the reliability, interestingness, and content volume, can be seen as a key stimulus. This stimulus directly influences the internal organism, i.e. the image of the cognitive destination in the mind of the tourist, then drives the desired reaction of visit intention. Notably, the affective part of the organism has been discovered to be indirectly affected by the cognitive representation, thus pointing to a subtle change of cognition to affect in the given context. We used the multi-group method (SEM) to analyze the moderating effects of word of mouth and perceived risk. Then, we concluded that the impact of the quality of information on Facebook pages would be better in light of a low-perceived risk than in light of a high one. In the same vein, a slightly negative word, picture or video, post or comment shared on a Facebook page may easily tarnish the destination image (Tunisia). Eventually, both word of mouth and perceived risk moderate the relationship between the quality of information and destination image formation.

Our empirical data analysis in the context of international tourists visiting “Discover Tunisia” Facebook page reconfirmed the destination image formation model proposed by Gartner (1993). This underscores that principal motivation of potential tourists to visit Tunisia is higher when they learn best about the destination’s tourist attractions (cognitive image) than when they have pleasant feelings toward the destination (affective image).

The present study has several valuable contributions to the theory. First of all, it builds on the stimulus-organism-response paradigm of the tourism literature by strictly mapping the process of translating the particular digital stimuli, i.e., the dimensions of information quality, into behavioral reactions through particular psychological mechanisms. The research recognizes reliability, interest, and amount of information as the key IQ variables integrated into social media that have an outstanding impact on the mental picture of a destination. In addition, it establishes that Word-of-mouth and perceived risk are important moderators, where information quality effect is magnified when perceived risk is low and when word-of-mouth is positive.

This study fills a relevant gap in the current body of knowledge by providing necessary empirical support to the process of destination image formation. And although the framework by Gartner (1993) is widely referenced, our quantitative analysis confirms its relevance to the modern social media environment, thus explaining that cognitive appraisal is a key predictor of visitation intention in the Tunisian context.

Methodologically, the study moves the debate further by developing and supporting a rigorous tool to gauge social media intelligence and its resultant impact, overcoming the largely conceptual or pure qualitative studies that have so far dominated this field.

The results offer profound insights on destination marketing organizations (DMOs) and practitioners:

• Focus on Cognitive Image by IQ: DMOs ought to selectively create content that is highly reliable, well elaborated, and interesting enough to directly strengthen the cognitive beliefs that potential tourists have about the destination.

• Perceived Risk and WOM Management: Marketing efforts should actively strive to reduce perceived risk through reinforcing safety measures, open communication and the like. They also need to promote good word-of-mouth, because these are some of the crucial elements in influencing information processing.

• Bringing in Tourists as Co-Creators: User-generated content by previous visitors could be a strong tool in building credibility and creating a positive and realistic cognitive image.

This research does not lack constraints. The focus on one platform (Facebook) and one national setting (Tunisia) call upon caution when extrapolating the results. Future studies ought to measure this S-O-R model on different social media platforms (e.g., Instagram, Tik Tok) and on different destinations. Furthermore, it would be worth extending the investigation to other types of tourism, including ecotourism, regenerative tourism, and associated sub-sectors. Also, moderating variables, including the previous experience of visiting the location and the type of tourism, may further enrich the model. To sum up, using the S-O-R framework as the basis to conduct our research, this study conclusively shows that in the digital age, the image of a destination will be co-created based on the quality of information shared on social media. In case of such a destination as Tunisia, the quality of information disclosed within social media platforms is not only an optional strategy but the key to competitive marketing and sustainable development.

References

Afshardoost, M., & Eshaghi, M. S. (2020). Destination image and tourist behavioural intentions: A meta-analysis. Tourism management, 81, 104154.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Agapito, D. (2020). The senses in tourism design: A bibliometric review. Annals of Tourism Research, 83, 102934.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Buhalis, D., & Moldavska, I. (2022). Voice assistants in hospitality: using artificial intelligence for customer service. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 13(3), 386-403.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Cheng, Y., & Wei, W. (2023). How does information quality of online reviews affect trust and purchase intention? The mediating role of cognitive and affective responses. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 73, 103326.

Dwivedi, Y. K., Ismagilova, E., Hughes, D. L., Carlson, J., Filieri, R., Jacobson, J., ... & Wang, Y. (2021). Setting the future of digital and social media marketing research: Perspectives and research propositions. International journal of information management, 59, 102168.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Jiang, S., & Lyu, J. (2022). The effect of destination image on tourists’ behavioral intentions: A meta-analysis. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 51, 1-11.

Kapoor, K. K., Tamilmani, K., Rana, N. P., Patil, P., Dwivedi, Y. K., & Nerur, S. (2018). Advances in social media research: Past, present and future. Information systems frontiers, 20(3), 531-558.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ketter, E. (2024). Destination Social Marketing: A Digital Perspective. Routledge.

Ketter, E. (2024). Instagram travel in the COVID-19 era: A holistic perspective on the use of social media for destination image building. Current Issues in Tourism, 27(4), 511-515.

Khan, A., et al. (2023). Political instability and tourism recovery. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management

Kim, J. H. (2021). The impact of memorable tourism experiences on loyalty and city branding: The mediating effect of destination image. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 21, 100637.

Mariani, M., Di Felice, M., & Mura, M. (2018). The role of social media in international tourism: A literature review. In Social Media in Travel, Tourism and Hospitality (pp. 13-31). Routledge.

Marine-Roig, E. (2019). Destination image analytics through traveller-generated content. Sustainability, 11(12), 3392.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Molinillo, S., Aguilar-Illescas, R., Anaya-Sánchez, R., & Liébana-Cabanillas, F. (2023). Social media communication and destination image: A systematic review. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 29, 100789.

Molinillo, S., Aguilar-Illescas, R., Anaya-Sánchez, R., & Liébana-Cabanillas, F. (2021). Social commerce website design, perceived value and loyalty behavior intentions: The moderating roles of gender, age and frequency of use. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 63, 102404.

Rather, R. A. (2021). Demystifying the effects of perceived risk and fear on customer engagement, co-creation and revisit intention during COVID-19: A protection motivation theory approach. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 20, 100564.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Sotiriadis, M. D. (2017). Sharing tourism experiences in social media: A literature review and a set of suggested business strategies. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(1), 179-225.

Stylos, N., Vassiliadis, C. A., Bellou, V., & Andronikidis, A. (2016). Destination images, holistic images and personal normative beliefs: Predictors of intention to revisit a destination. Tourism management, 53, 40-60.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Wang, D., Chen, Y., Tuguinay, J., & Yuan, J. J. (2023). The influence of perceived risks and behavioral intention: The case of Chinese international students. Sage Open, 13(2), 21582440231183435.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Wen, J., et al. (2023). Post-pandemic tourist behaviour and risk perception. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management

World Travel & Tourism Council (2024). Economic Impact Report. London: WTTC.

Yousaf, A., et al. (2023). Social media and destination image. Tourism Management Perspectives

Zhang, H., Wu, Y., & Buhalis, D. (2024). The effect of augmented reality on destination image: The mediating role of cognitive and affective evaluation. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 15(1), 2-19.

Zhou, S., Yan, Q., Yan, M., & Shen, H. (2024). More than just likes: The differential impact of visual and textual information quality on travel intention. Journal of Travel Research, 63(1), 127-144.

Received: 04-Dec-2025, Manuscript No. AMSJ-25-16328; Editor assigned: 10-Dec-2025, PreQC No. AMSJ-25-16328(PQ); Reviewed: 18-Dec-2025, QC No. AMSJ-25-16328; Revised: 24-Dec-2025, Manuscript No. AMSJ-25-16328(R); Published: 30-Dec-2025